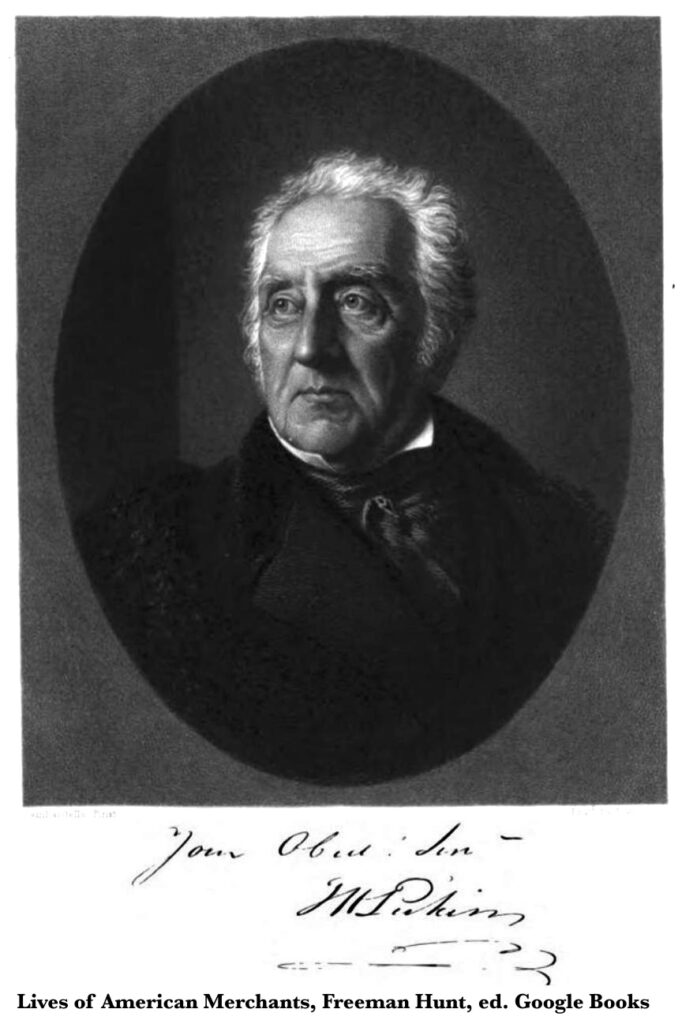

Thomas Handasyd Perkins (December 15, 1764-January 11, 1854) was a successful China trade merchant, a philanthropist, an important Boston Federalist, a leader in the cultural life of Boston, and the founding patron of the world-renowned Perkins School for the Blind. He was a faithful member of the congregation of the Federal Street Church during the ministries of Jeremy Belknap, William Ellery Channing, and Ezra Stiles Gannett.

Thomas Handasyd Perkins (December 15, 1764-January 11, 1854) was a successful China trade merchant, a philanthropist, an important Boston Federalist, a leader in the cultural life of Boston, and the founding patron of the world-renowned Perkins School for the Blind. He was a faithful member of the congregation of the Federal Street Church during the ministries of Jeremy Belknap, William Ellery Channing, and Ezra Stiles Gannett.

Born in Boston, Thomas grew up during the American Revolution. When he was twelve he was in the crowd which first heard the Declaration of Independence read to the citizens of Boston. His parents, James Perkins and Elizabeth Peck, had ten children in eighteen years. James ran a store that sold such household items as cheese, tea, sugar, and wine. When he died at forty in 1773, his wife took over the the store. Under her management it prospered as never before.

The family originally planned to send Thomas to Harvard, but he had no interest in a college education. In 1779 he worked for a year in a retail store run by William Dall and then moved to the larger mercantile firm of W. & J. Shattuck. When he turned 21 he became legally entitled to a small bequest that had been left to him by his grandfather Peck. With it he left Boston for Cape Francis in Saint-Domingue (later Haiti) to seek his worldly fortune.

His brother James was already engaged in business at Cape Francis as a commission agent for several North American merchants. Together with a friend in 1786 they founded their own commission firm, Perkins, Burling & Perkins. They traded profitably in slaves, flour, horses, and dried fish. This was the first of a long series of business partnerships in which the two Perkins brothers were always the ones who ran the business. The Perkins credo, as Thomas wrote James, was: “Now is the heyday of life, let us improve it, and when the inclination and ability for exertion is over, let us have it in our power to retire from the bustle of the world and enjoy the fruits of our labour.”

In 1788 Perkins was married to Sally Elliot at the Federal Street Church by Jeremy Belknap. Sally’s father ran a tobacconist shop near the Perkins house. While Thomas spent most of the first year of their marriage at Cape Francis, Sally lived in their new Boston home. They were married over sixty years and had eleven children. After the birth of their first child, Thomas returned to Boston and formed a partnership with James Magee, an uncle by marriage. T. H. Perkins & James Magee sold wines, spirits, sherry, iron, flour, lumber, and oil on commission for others. Thomas’s place in the West Indies was taken over by his brother Samuel.

In 1785 China opened the port of Canton to foreign businesses. Perkins was one of the first Boston merchants to engage in this risky yet profitable trade. In 1789 he sailed on the Astrea to Canton. Its cargo included ginseng, cheese, lard, wine, and iron. On the trip back it carried tea and cotton cloth. As the trade developed, his ships went first to the coast of the Pacific Northwest to trade for furs from the native American Indians, and then to China to exchange the skins for Chinese goods. The China trade made Perkins a millionaire.

The Perkins’s Saint-Domingue business collapsed as a result of the revolution which began there in 1791. They recouped, however, when in 1794 Thomas traveled to London and Paris and arranged to use his neutral vessels to carry on the trade between France and the West Indies. A friend later wrote him from London that many merchants and bankers there considered him “rather a clever fellow.”

Early in his career Perkins began to take an active part in public affairs. He joined the Federalists, the party of Washington and Hamilton and the one that reflected his conservative views. On several occasions he was elected to the Massachusetts House and Senate. He was also one of the original members of the reorganized Independent Corps of Cadets, the local militia, rising in rank by 1799 to lieutenant colonel. He was afterwards called Colonel Perkins.

The Perkins brothers were busy merchants during the closing years of the eighteenth century and the first decades of the new one. They had three basic business strategies: short speculations in the West Indies, longer ones in Europe, and major investments in the growing China market. They acquired a fleet of their own ships. In 1803 they opened a branch office of the firm in Canton, giving them better access to and allowing more profitable business relations with the local Chinese merchants.

Although President Thomas Jefferson‘s Embargo of 1807 lasted fifteen months, it did little harm to J. & T. H. Perkins. It enabled them to get rid of their local stock and to buy at their Canton office new goods at prices lower than usual. When the first batch of these items reached New York after the embargo was lifted the Perkins firm realized a profit of $100,000. Then the War of 1812 for a time nearly brought their trading business to a standstill. Fortunately, when the war ended they had a well-laden ship on its way home from Canton. An important key to the Perkins success had always been their ability to make the right decisions at the right time.

T.H.P., as he was often called, was by 1810 also engaged in other business ventures. He was, for example, the driving force behind the Monkton Iron Company in Vermont. At the same time he participated in Andrew Craigie’s land and bridge speculations in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In 1815 the brothers, still retaining their keen spirit of business adventure, opened a Mediterranean office to buy Turkish opium for resale in China. Neither were concerned with the morality of selling slaves or opium. All that mattered to them was that what they traded should make money for the firm. Thomas’s minister, William Ellery Channing, did not appreciate merchants much, even those in his congregation, and later condemned the business of slavery. “I see not how men absorbed in business,” Channing wrote in 1834, “can accomplish the great end of life. That end is to strengthen, to extend and keep in invigorating action, the principles of love to God and to our fellow creatures.”

In 1815 the brothers, still retaining their keen spirit of business adventure, opened a Mediterranean office to buy Turkish opium for resale in China. Neither were concerned with the morality of selling slaves or opium. All that mattered to them was that what they traded should make money for the firm. Thomas’s minister, William Ellery Channing, did not appreciate merchants much, even those in his congregation, and later condemned the business of slavery. “I see not how men absorbed in business,” Channing wrote in 1834, “can accomplish the great end of life. That end is to strengthen, to extend and keep in invigorating action, the principles of love to God and to our fellow creatures.”

James Perkins died in 1822. In one sense that was the end of the firm. But Colonel Thomas Perkins never fully retired. Even after much of the business was turned over to younger members of his family, among them his great-nephew John Murray Forbes, he continued to dream up new ways to make money. In 1825 Perkins was instrumental in encouraging the purchase of a granite quarry in Quincy, Massachusetts and then, to move the granite, in developing one of the first horse-drawn railways in America, the Granite Railway. The granite was needed for the Bunker Hill monument. After he had discovered the beauty and allure of Nahant, he constructed and oversaw the first hotel there for wealthy summer visitors. Later he invested in building the famous Tremont House, the most modern hotel yet seen in Boston. His resources and his business experience fostered the pioneering cotton mills in Newton and Lowell, Massachusetts.

Perkins always loved the outdoors and nature and enjoyed gardening, hunting, fishing, and traveling. During his lifetime he made ten trips to England and the continent, as much for pleasure as for business. He also enjoyed traveling about America. In 1837, when he was 73, with a grandson he visited 23 states in 110 days. During his last years he spent several summers at Saratoga more for the company of its “fashionable people” than for its waters. Besides sightseeing he enjoyed the theater and visiting art museums. He knew many of the artists of his time and regularly purchased their work.

The “merchant prince” was just as generous to many causes and institutions that he felt were important elements of a good society. He, and especially his brother James, were long associated with the Boston Athenaeum. The Colonel not only supported it financially but also served as president, 1830-1832. He was one of the founders of the Massachusetts General Hospital. A member of the Monument Association, he helped to pay for the Bunker Hill Monument and the Washington Monument. His most notable patronage, however, was of the celebrated Perkins School for the Blind. Impressed by the work with the blind of Samuel Gridley Howe and interested, as he wrote, in “the fate of this class of the human family,” he offered his Pearl Street home as the school’s first residence. As the school quickly grew under Howe’s able leadership and care, in 1839 Perkins sold the house and gave the proceeds to the school to enable them to purchase and adapt a hotel building in South Boston.

Perkins died quietly at his home at the start of his eighty-ninth year. His funeral was held at the Federal Street Church. Out of respect the state legislature adjourned so its members could attend the service. The governor, the officers of the Boston Athenaeum, and Dr. Howe from the Perkins Institute for the Blind were present. The choir was made up of children from the Institute. It was a gathering, noted the Daily Evening Traveller, of “the intellectual and the wealthy of the city.” Perkins’s remains were buried in the family plot at Mt. Auburn Cemetery.

The bulk of the Perkins papers are at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Additional material can also be found there in the collections of his associates and friends. Baker Library of the Harvard Business School and the Schlesinger Library at Harvard also have useful items. The definitive biography is Carl Seaburg and Stanley Paterson, Merchant Prince of Boston: Colonel T. H. Perkins, 1764-1854 (1971). See also Thomas G. Cary, Memoir of T. H. Perkins (1856). There is a biographical entry by Peter C. Holloran in American National Biography (1999).

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted August 18, 2004 – second portrait added October 2, 2013