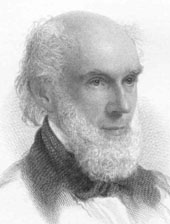

Ezra Stiles Gannett (May 4, 1801-August 26, 1871) was a prominent Unitarian minister, editor, and a founder of the American Unitarian Association (AUA). He was the colleague pastor, and successor, to William Ellery Channing at the Federal Street Church in Boston, Massachusetts. He is most remembered as a leading defender of Unitarian “orthodoxy” against the challenge of Theodore Parker and the Transcendentalists. His even-handed and principled stand narrowly prevented the Boston Association of Congregational Ministers, an organization of Unitarian clergy, from formally expelling Parker.

Ezra was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His father, Caleb Gannett, the first in his family to go to college, was a moderately orthodox minister and later Professor of Mathematics and Steward of Harvard College. Upon the death of his first wife, with whom he had four children, Caleb married Ruth Stiles, the profoundly devout daughter of the formidable Ezra Stiles, President of Yale College. Ezra was the only child of this union. His mother died when he was seven, his father a decade later.

At Phillips Academy in Andover and at a preparatory school run by John G. Palfrey, Ezra was admired by fellow students for his unusually pious and serious manner. He maintained this reputation after he entered Harvard in 1816.

Gannett’s college years coincided with the height of the Unitarian controversy. The religious views he formed at this time, and held all his life, were those of the Unitarian party led by William Ellery Channing. In notes for his college thesis on theology, written a year after Channing’s sermon Unitarian Christianity, Gannett claimed “the right of private judgment” and the usefulness of reason in the interpretation of scripture. Among the errors that had crept into religion, in his estimation, were the “unintelligible” doctrine of the Trinity, the “repugnant” and “highly dangerous” doctrine of election, and the “absurd” doctrine of infinite sin. He nevertheless showed profound reverence for revealed religion, including the miracles, whose evidence he believed “the highest which can be brought in proof of any system.”

Upon graduation with highest honors in 1820, Gannett entered the recently organized Divinity School. He studied the ministerial arts under Henry Ware, Sr. and biblical interpretation and exegesis under Andrews Norton. In late 1823 Channing enlisted him to preach half-time at the Federal Street Church. As a result, early in 1824 Gannett was called to be Channing’s colleague pastor. At first overawed by Channing’s venerability and “saintliness” and worried that his parishioners would be disappointed when he replaced his senior in the pulpit, Gannett quickly earned the trust of the congregation by his earnest and energetic pastoral work.

Although Channing and many other liberals feared sectarianism, Gannett early on saw the necessity of a separate Unitarian institutional organization. In 1825 he participated in the discussions that led to the founding of the American Unitarian Association (AUA). He wrote the constitution and was chosen the first Secretary. “His whole soul is in it,” Henry Ware, Jr. commented.

“The American Unitarian Association had its origin, not in a sectarian purpose, but in a desire to promote the increase of religion in the land,” Gannett later wrote. “We found ourselves under the painful necessity of contributing our assistance to [false] views, or of forming an Association through which we might address the great truths of religion to our fellow-men, without the adulteration of erroneous dogmas. To take one of these two courses, or to do nothing in the way of Christian beneficence, was the only alternative permitted us. The name which was adopted has a sectarian sound. But it was chosen to avoid equivocation on the one hand, and misapprehension on the other.”

The AUA sought to increase its scope by sending missionaries to the west and creating periodicals. Gannett favored active evangelistic effort and spoke tirelessly in promotion of the AUA. The historian Joseph Henry Allen would later say that “ten such men [as Gannett] would have carried Unitarianism like a prairie fire from border to border of our country.” The majority of Unitarian leaders, however, shunned proselytizing in favor of literary endeavor. Gannett undertook more than his share of this work, founding and editing the Scriptural Interpreter, 1831-35 and the Monthly Miscellany, 1840-43. He also edited the Christian Examiner, 1844-49. In 1844 he became the President of the AUA, a position he held for five years.

In 1835 Gannett married Anna Linzee Tilden (1811-1846), a teacher and an active member of Federal Street Church. While he had roomed in the Tilden home, Anna had turned to him with her theological concerns. She had, Gannett later noted, “a natural inclination to the side of doubt rather than of faith, and she looked at the great truths of religion with the eye of an anxious curiosity.” Her notes on sermons of Channing, Henry Ware, Sr. and Jr., Orville Dewey, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and young Gannett himself reveal her studious nature and her earnest interest in Unitarianism. They had three children, including the reformer Kate Gannett Wells and the Unitarian minister William Channing Gannett, who, more radical than his father in theology, was a supporter of the Free Religious Association.

The year after their marriage, Gannett’s intense work habits coupled with low self-esteem led to a nervous breakdown, and he was forced to take a prolonged rest in Europe. During the first part of his absence Anna provided counsel to church members, and her letters kept her husband abreast of news of the congregation and informing him of the controversy over miracles begun by George Ripley and Andrews Norton. Anna joined her husband in London in 1837. Gannett soon wrote, “For the first time during many weeks I have within the last two days cherished the thought that I may return to my ministry.”

Upon their return the following year the Gannetts finally set up home together and Ezra thrived as a preacher. In 1840, however, he was incapacitated by a stroke that permanently paralyzed his right leg. Afterwards he used of a pair of canes. His son William records, “They [the canes] became a part of him, the signal to eye and ear, by which every one knew ‘Dr. Gannett’ in Boston streets.”

An intensely conscientious and self-critical minister, Gannett alternated throughout his career between times of intense work and periods of mental and physical exhaustion. During his collapses he depended upon his wife’s strong support, physically and intellectually, and her service as liaison with the congregation. When she died in childbirth in 1846, Gannett suffered a severe emotional and professional loss. He never remarried.

In 1843 Harvard University awarded Gannett a Doctor of Divinity degree. Characteristically modest, he recorded that he was “altogether destitute of the learning or the character which might entitle me to it.” He thought it likely that he owed the honor to Harvard President Josiah Quincy, who had once been his parishioner.

Meanwhile, further controversy was brewing among Unitarians. In 1841 Theodore Parker, at that time minister of the Unitarian church at West Roxbury, gave his seminal sermon, Discourse on the Transient and Permanent in Christianity, in which he denied the authority of the scriptures and of the words of Jesus except insofar as they reflected true and “absolute” religion. Many Unitarians—including Gannett—were disturbed by Parker’s views, seeing them as a repudiation of the special revelation of Christianity. In Gannett’s estimation, Parker’s doubts about the truth of scripture cast doubt upon everything known about the past. “If the New Testament cannot be believed,” he argued, “reliance upon historical testimony becomes unjustifiable. We can know nothing of the past.” More importantly, Gannett believed that intuition, on which Parker based his faith, was an unsatisfactory foundation for Christianity. Disbelief in miracles would lead most people, if not all, eventually into doubt, despair, and even immorality.

Gannett had also personal reason to oppose Parker. He felt betrayed by Parker’s October 1842 critique in the Transcendentalist journal, the Dial, of the 1841 Hollis Street Council. This ecclesiastical tribunal had attempted to resolve a bitter public dispute between the conservative Proprietors of the Hollis Street Church and its minister, John Pierpont, a crusading reformer. Parker denounced the final report of the council, which Gannett had helped to write, as a dishonest document, which sought to undermine Pierpont under a show of impartiality. After Parker refused to retract or qualify what he had written, Gannett told the Boston Association, “I will say that I freely & from my heart forgive him, as I hope God Allmighty will forgive me—but I can never grasp him by the hand again cordially.”

Within the Boston Association, Gannett nevertheless resisted pressure from Samuel K. Lothrop and other more conservative Unitarians to pass a motion expelling Parker from their ranks. He understood that because the Unitarians themselves had earlier complained about the orthodox Congregationalists who had treated them as outcasts, any exclusion of Parker would open them to a charge of hypocrisy. Furthermore, Gannett vehemently opposed the establishment of a Unitarian creed. “Expulsion of a member for not thinking with his brethren,” wrote Gannett, “however wrong his way of thinking, and however pernicious the influence of his teaching may be in their eyes, is not an act which that association contemplate among their privileges or their duties; nor do they come together to draw up statements of belief, whether for their own benefit or for the satisfaction of others.”

Gannett continued to grapple with the issue of Parker’s vexed relationship with the Boston Association until 1846, when Parker automatically lost his membership by leaving his West Roxbury parish for the new 28th Congregational Society in Boston.

Gannett was among the great majority of Boston area Unitarian ministers who refused to exchange pulpits with Parker. Although he argued against silencing Parker, except through “open argument and fraternal persuasion,” he contended that Unitarians like himself who thought Parker’s views reduced public confidence in Unitarianism were not obligated to assist or encourage him. Instead of ministerial fellowship, Gannett offered Parker a more general “Christian fellowship.” He thought it fair to point out that Parker’s general teaching and preaching showed him to be a believer and teacher of Christian values and truth.

As Parker’s views became widespread among Unitarians, Gannett remained steadfast in his more conservative theological beliefs, stating that Unitarian Christianity “declares that there is one God, supreme and perfect, of spotless holiness: who is alone God. He hath saved and is saving men by sending His Son, Jesus Christ to be a teacher of righteousness and a mediator to reconcile the disobedient to himself through repentance.”

Gannett again locked horns with radical Unitarians over the issue of slavery. In the 1830s he had advised Channing to avoid being provocative about slavery and to be “prudent, slow, and solicitous.” It was not primarily reluctance to cross the wealthy and powerful Federal Street congregation that set Gannett in opposition to the anti-slavery movement. He greatly deplored the excesses of the abolitionists. “I may sympathize in their objects,” he declared, “while I dread and abhor their spirit.” He was devoted to the cause of peace and refused to hate the slaveholders as he hated slavery. When Samuel J. May offered an anti-slavery resolution at a meeting of the AUA in 1844, Gannett opposed it as “an invasion of rights of conscience” and the creation of “a creed on the subject.”

Because he thought that preservation of the Union depended on maintaining federal laws, in 1850 Gannett reluctantly supported the Fugitive Slave Act. In his congregation, moreover, were offials who enforced it. Parker, a fervent abolitionist whose church included several escaped slaves, famously declared that Gannett was “calling on his church members to kidnap mine and sell them into bondage forever.” May reported that Gannett had said that “he should feel it to be his duty to turn away from his door a fugitive slave, —unfed, unaided in any way, rather than set at naught the law of the land.” (Parker, who despite everything respected Gannett, commented in his journal that he had no doubt Gannett had said this, but that he also had no doubt Gannett would not in fact, when faced with an actual fugitive, do any such thing.)

The arrest in Boston of Anthony Burns as a fugitive slave in 1854, and the violent protests that resulted, changed Gannett’s mind about the infamous law. He no longer thought the Union worth preserving at such a cost. He risked the disapproval of his congregation by preaching that “our national administration and our free soil must not be used to promote the interests of slavery.’ When his daughter then asked him, “What if the slave came to your door?” Gannett answered, “If he comes to-night, or at any time, I should shelter him and aid him to go further on to Canada, and then I should go and give myself up to prison, and insist of being made a prisoner, would accept of no release.”

The events leading up to the Civil War caused Gannett to revise downward his initially optimistic Unitarian view of human nature. As a pacifist he did not preach in support of the war; hoping that the Union might be preserved, he made no public statement against it. Only in the Freedmen’s Aid Society could he find a cause that he could whole-heartedly support.

Gannett served his congregation for 47 years, becoming senior minister upon the death of Channing in 1842. He guided the church through its 1861 move from Federal Street to Arlington Street, where it is located to this day. He was, in his final years, an august and revered presence for his congregation and in the AUA. The high view he held of his calling never changed, and his desire to serve, which always dominated his personality, manifested itself in countless acts of kindness great and small and in preaching and teaching.

Death

Gannett died in a train accident outside Boston. Frederic Henry Hedge told the Arlington Street Church, “Yours has been a privileged church; enjoying the ministrations of two men, of whom, though differing with the widest difference, each has been a model of his kind. The intellect of Channing, the heart of Gannett, have been yours. It were difficult to say from whose sowing has sprung and is to spring the richest fruit.”

Sources

Gannett’s papers are at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts. There are also letters among the papers of William Channing Gannett at the University of Rochester in Rochester, New York and among the Lewis Gannett papers at the Houghton Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts. By far the most complete account of Gannett’s life is Ezra Stiles Gannett: Unitarian Minister in Boston (1875) by his son William Channing Gannett. It includes several sermons and a complete inventory of Gannett’s published works. There are short biographical articles in Samuel A. Eliot, ed., Heralds of a Liberal Faith, vol. 3 (1910) and American National Biography (1999). Accounts of the controversy with Parker can be found in William R. Hutchinson, The Transcendentalist Ministers: Church Reform in the New England Renaissance (1959); Conrad Wright, editor, A Stream of Light: A Short History of American Unitarianism (1975); and most recently Dean Grodzins, American Heretic: Theodore Parker and Transcendentalism (2002). Other sources include John Ware, Memoir of the Life of Henry Ware, Jr. (1846); Henry Steele Commager, Theodore Parker (1936); William Henry Channing, Memoir of William Ellery Channing (1848); and Samuel J. May, Some Recollections of Our Antislavery Conflict (1869). On Anna Tilden Gannett see Sarah Ann Wider, Anna Tilden, Unitarian Culture, and the Problem of Self-Representation (1997) and Emily Mace, “In the Parsonage, In the Parish: Experiences of Nineteenth Century Unitarian Ministers’ Wives,” Unitarian Universalist Women’s Heritage Society Occasional Paper (2002).

Article by Stuart Twite

Posted posted February 14, 2004