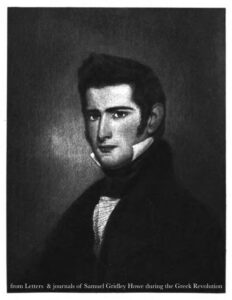

Samuel Gridley Howe (November 10, 1801-January 9, 1876), founding director of the Perkins School for the Blind, was a leading figure in the early history of special education in the United States. He was also a military hero in the Greek War of Independence, a campaigner for the abolition of slavery, and an advocate for prison reform. He worked for the mentally disabled with Dorothea Dix and for universal public education with Horace Mann. His work with Laura Bridgman, the first deaf-blind person to acquire the skill of intelligent conversation, inspired Anne Sullivan, the teacher of Helen Keller.

Samuel was born in Boston, the second son of Patty Gridley and Joseph Neals Howe, a rope manufacturer. He was baptized by the Reverend Peter Thatcher at the Brattle Street Church on November 22, 1801. Reverend Thatcher was a religious liberal. After Thatcher’s death in 1802, a succession of ministers (Joseph S. Buckminster, Edward Everett, John Gorham Palfrey) steadily guided the Brattle Street congregation into the Unitarian fold, and it formally acknowledged its place there in 1825-26. The Howe family supported their ministers and their church.

What distinguished the Howes from their neighbors was not that they were Unitarians, but that they were Jeffersonian Democrats and enthusiastic about the possibilities of the French Revolution. Most Bostonians, strongly Federalist and supporters of John Adams, thought that one revolution had been quite enough. Samuel got into fist fights with his classmates who taunted him as a Jacobin.

During the War of 1812, Joseph Howe had unwisely taken Treasury notes as payment from the United States government for cordage. After they dropped in value, he could only afford to send one of his three sons to college, so he held a contest in which each of his sons read aloud a Bible passage. Samuel won and attended Brown College in Providence, Rhode Island, 1817-21. At Brown he was an enthusiastic participant in the rowdy behavior that was common among college students. He and a few friends led the college president’s horse on a midnight trip to the belfry of the main college building. When they were discovered by the classical language tutor Horace Mann, his classmates fled leaving Howe holding the reins. Mann offered not to report Samuel if he helped return the horse to the stables. This escapade was the beginning of their lifelong friendship.

Both men would be lifelong Unitarians. While Howe was a firm believer in education and reason, he did not share the optimism about human nature prevalent in the preaching of William Ellery Channing and others. Howe’s beliefs were tempered by the realism of one who was more a doer than a thinker. Near the close of his undergraduate days, he wrote: “Knowledge, alone, can free men from error; and it is impossible that the diffusion of this should ever become so general, as to produce the effect; for the lower classes always have, and always must, continue in ignorance, and be the dupes of others.”

After Brown, Howe attended Harvard Medical School, 1821-24. His father expected him to take up the medical profession and settle down. Instead Howe spent the years 1825-30 fighting for the independence of Greece, serving as battlefield surgeon, soldier, director of a medical and relief program, fund-raiser, publicist, engineer, and director of an agricultural utopian community. With money he raised in North America, he put together a public works project rebuilding the harbor at Aegina. He educated and ruled over his utopian community, “Washingtonia,” near Corinth, for about a year before he was driven out by a conflict with a new administration in the Greek government. A few years—and another administration later, the newly installed Greek monarch made him Chevalier of the Order of St. Savior. Howe put aside his anti-monarchist sentiments and gratefully received the honor. From then on his friends and family referred to him as the Chevalier or “Chev.”

Returning to Boston in 1831, Howe wanted to work to reform society. A friend from Brown, John Dix Fisher who had recently founded the New England Asylum for the Blind, offered him the position of director. Howe was sent to Europe during 1831-32 to study recent developments in the education of the blind. He was eager to learn what he could in Europe, yet he also believed that America, with its democratic theories of education, would soon surpass anything accomplished in Europe.

While in Europe, Howe became entangled in the Polish revolt against Russia. While attempting to distribute funds to Polish refugees in Berlin, he was arrested and spent five weeks in prison before the American minister at Paris arranged for his release.

Back in Boston in July of 1832, Howe began his work with the blind by tutoring a few students in a room at his father’s house. He demonstrated enough progress that within a year the Massachusetts legislature approved $30,000 a year funding with the proviso that 20 students from poor families be given full scholarships. Then Colonel Thomas Handasyd Perkins, a prominent Boston merchant, whose fortune had been partly acquired through trading in slaves and opium, donated his mansion and grounds on Pearl Street for the school’s use. After that, the school was known as the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts Asylum (or, since 1877, School) for the Blind.

The school quickly developed a national reputation as a center for innovation, serving as a model for other institutions. Howe produced the first raised-type printing press in America (Braille, invented in 1821 as a military code, would not gain popular acceptance until the 1870’s). Howe wanted his students to experience the world as much like sighted people as possible. Hence, he taught his students to make letters with their fingers, but opposed the use of symbols or other means of communication that would separate the deaf and blind community from the seeing community.

In the education of Laura Bridgman, who came under his tutelage in 1837, Howe achieved a breakthrough in the history of education. Never before had someone who was both blind and deaf been taught to communicate. Howe began Laura’s instruction by giving her familiar objects (a key, a spoon, a fork) with raised labels attached. After several days he then gave her the objects in one hand, and the labels in the other. She soon learned to attach the labels to the correct objects, and after some weeks, she began to understand the labels as symbols for the objects. In his report Howe wrote: “All at once her countenance lighted up . . . it was an immortal spirit, eagerly seizing a new link of union with other spirits.”

The whole world soon knew about Bridgman and her teacher. There were implications not only for the education of those with special needs, but education in general.

The prevailing Calvinist attitude of the previous generations had held that human nature was inherently corrupt and that education involved using steady punishments and occasional rewards to suppress a child’s basic nature. The emerging Unitarian theology held that human nature was basically good. Its methods of education, championed by Horace Mann and others, involved steady rewards and occasional punishments or even the total elimination of punishments. A child’s natural curiosity was to be celebrated: It was a thirst for knowledge that would ultimately lead to reverence for the Divine.

Before Howe taught Bridgman to communicate, many educated people doubted whether she really had a soul. Now that it was clear that she possessed one, many were concerned about it. Howe gave careful instructions that no one was to talk to Laura about God. If she asked questions, the staff was to assure her that the doctor would explain this to her when she was older. He selected the passages of the Bible that she would be given to read. He gave her lessons in botany and physics with the thought that this would ultimately lead her to discover God on her own, or at least be prepared to understand God the way Howe intended that she should—a God who had designed a rational universe and the understanding of whom is best reached through knowledge of the universe.

This was in keeping, but not identical, with contemporary Transcendentalist beliefs. Pure Transcendentalism was more mystical, more interested in communion with nature than the study of nature. Conservative Unitarians feared that the Transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson and others relied too heavily on individual intuition and too little on the authority of Scripture. Although Howe shared the concern about trusting intuition, he put his faith not in Scripture, but in “Baconian science, with its clear, rational, and inductively derived laws of nature.”

Howe’s relationship with his star pupil was complex. He presented an image of Laura Bridgeman to the public that was obedient, pure and innocent while Bridgman viewed herself as willful, selfish, and—like Howe himself—short-tempered. She had many teachers, including Howe, who let her know when she was exhibiting these behaviors. Unlike Howe, she was sometimes given to periods of self-doubt.

While Howe was committed to democratic principles, he never failed to grasp the reins of authority when they were offered to him. He generally behaved as if the world would be a better place if decisions were left to him. Harlan Lane, the preeminent historian of the deaf community, condemned Howe as an “arrogant, contentious man who found in reform both an excuse and an outlet for his aggression.” Both Bridgman and Howe’s wife Julia, were always more generous in their assessment of the man who ran their life, but whose will for total control they always resisted.

One of the thousands of visitors who came to view Howe’s accomplishments at the Perkins School was a beautiful young socialite from New York City, Julia Ward. Once Howe began courting Julia he spent less time with Bridgeman. After their marriage in 1843, they left for an extended honeymoon in Europe. The marriage unsettled Bridgeman and she experienced a crisis of faith. Howe had told her that God welcomes good people into heaven, leaving open the question of what happens to the rest. During his honeymoon, when Bridgman read in a raised-letter Book of Psalms that “God is angry with the wicked every day,” she feared that she was among the wicked. His responses to her two frantic letters were meant to comfort, but did not give the assurances for which she longed.

One of the thousands of visitors who came to view Howe’s accomplishments at the Perkins School was a beautiful young socialite from New York City, Julia Ward. Once Howe began courting Julia he spent less time with Bridgeman. After their marriage in 1843, they left for an extended honeymoon in Europe. The marriage unsettled Bridgeman and she experienced a crisis of faith. Howe had told her that God welcomes good people into heaven, leaving open the question of what happens to the rest. During his honeymoon, when Bridgman read in a raised-letter Book of Psalms that “God is angry with the wicked every day,” she feared that she was among the wicked. His responses to her two frantic letters were meant to comfort, but did not give the assurances for which she longed.

Mary Swift, a teacher at the school, defied Howe’s instructions and taught Bridgman that Jesus’ atonement appeased God’s wrath and Bridgman took comfort in the idea of Jesus as her personal savior whose sufferings atoned for her own sinfulness. Although Swift later denied it, Howe was convinced that she had arranged for Laura to receive a number of Evangelical visitors. These were the same people who were opposing Horace Mann’s efforts to remove Calvinist instruction from the public schools. They believed Howe and Mann were preparing to use Laura to forward a Unitarian agenda. Howe frequently declared that the disruption of Bridgman’s religious education was the greatest disappointment of his life. Years later he would still rage about it. Although he went on to other projects, and Laura Bridgman had a public life apart from Howe, the two remained loyal to each other to the end of their days. Howe even left Bridgman a small inheritance.

Howe had set up the Perkins School in such a way that he could serve as the director and still have time to pursue other projects. He joined Dorothea Dix in her crusade on behalf of the mentally disabled. Persons with special needs were often referred to as idiots during the first half of the nineteenth century: many were kept in jails with no thought of separating them from the general prison population. Although Dix was a tireless worker, she never wanted to be a public speaker, so Howe presented her findings to the Massachusetts legislature. In 1847 they appropriated funds for ten carefully chosen students and a teacher who would reside in a wing of the Perkins Institute. The students demonstrated enough progress that in 1856 the legislature appropriated funds for a permanent “Massachusetts School for Idiots and Feeble-Minded Youth.” It was located near the Perkins Institute and Howe was its first director.

From 1851 to 1853 Samuel and Julia Howe briefly worked together on an abolitionist paper, the Commonwealth. Howe had gained first-hand exposure to slavery in the winter of 1841-42. In a letter to his friend Charles Sumner, he wrote of his frustrations in suppressing his desires to immediately speak out against the injustices he witnessed lest it jeopardize his mission to found a new school for the deaf in Kentucky.

Howe was an active member of the political insider group known as the Bird Club. Begun informally by Francis W. Bird, the group lunched together every Saturday afternoon. Its forty or so members included state and federal legislators and former and future governors of Massachusetts. It was with such connections that in 1845 Howe formed the Massachusetts Committee to Prevent the Admission of Texas as a Slave State. In 1855 Howe became the director of the Kansas Emigrant Aid Company, formed to assist free-soil New Englanders to settle in Kansas to prevent it from becoming a slave state. During this period he also headed the Massachusetts Kansas Aid Committee and was one of the leaders of the National Kansas Aid Committee. Some of the money raised by these committees would go to John Brown.

Howe told his wife about meeting a man who “seemed to intend to devote his life to the redemption of the colored race from slavery, even as Christ had willingly offered his life for the salvation of mankind.” After John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, federal troops went to the farmhouse from which Brown had launched his raid and found letters and other documents that indicated that the raid had been financed by six well-connected Northerners. Called the “secret six,” five were Unitarians: Howe, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker, Franklin Sanborn, and George L. Stearns. The sixth member of the “secret six” was abolitionist, Gerrit Smith, a member of a non-sectarian Church. Howe wrote a public letter saying that he did not know in advance about Brown’s plan. While it is improbable that he knew the details, he probably did know that Brown was buying guns for a slave insurrection. Congress called on Howe and the others to testify in Washington. They feared it was a snare to kidnap them to stand trial in Virginia. John A. Andrew, a Bird Club Member and soon to be governor of Massachusetts served as their lawyer and arranged for them to give testimony in Boston. Then Howe, Sanborn, and Stearns, spent some weeks in Canada until things cooled down. Parker had already gone to Italy.

Of all the husbands of prominent women in the ninthteenth-century, Howe stands out as one of the least supportive. He forbade his wife to manage her own funds, publish her writings, or speak publicly. She wrote and spoke anyway. They quarreled about money and other matters all of their married life. After his death, Julia became a major figure in the struggle for women’s rights. She publicly maintained that they had enjoyed a good marriage, even if it had weathered stormy seasons. They had six children (five of whom lived to adulthood). Two of their children, Laura and Maude, later wrote the life stories of their famous parents. In 1917 they won the first Pulitzer Prize for biography for their book, Julia Ward Howe (1917).

During their honeymoon in Rome in 1843, the Howes had become friends with the radical Unitarian clergyman, Theodore Parker. For the next 16 years Howe and Parker corresponded. After Parker’s death in 1860, his brain (preserved in a glass jar) was sent back to America and given to Dr. Howe, presumably so that it might be analyzed by later generations. Even though Julia found Theodore Parker more agreeable than his reputation had led her to expect, she still wanted to attend a more traditional church than Parker’s Boston Music Hall congregation. One of the few happy compromises in the Howe’s tumultuous marriage was their decision to become members of the Church of the Disciples, where James Freeman Clarke served as their minister.

During the Civil War both Samuel and Julia joined Clarke and many other Unitarians to support the United States Sanitary Commission, the precursor to the American Red Cross that provided medical support to the Union Troops. It was through this connection that they found themselves in Washington D.C. sitting in an open carriage stalled in traffic while Union troops marched by singing “John Brown’s Body.” Clarke, knowing that Julia wrote poetry, suggested she write more uplifting words for that tune. That evening she wrote the “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

Howe had wanted to serve as a commander in the Union Army, but was considered too old. There may also have been concerns about his ability to take orders from other people. In 1863 he was invited to lead a federal commission to visit Canada and study how free blacks lived there. The commission reported that blacks in Canada lived pretty much the same way as whites did. It recommended that after the war, blacks in the United States should be allowed to live however they choose.

In 1870 the leader of Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) petitioned the United States to take control of his country. President Grant, in favor of the idea, appointed a three member commission to visit the island and issue a report. Some suggested, and others feared, that black Americans might be shipped off to Santo Domingo. Part of the reason Grant chose Howe was to quell the opposition from Sumner (then chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee). Although Grant got the report he wanted, it did not diminish Sumner’s opposition.

Howe nearly embraced an even worse plan for the Dominican Republic. A group of investors, who saw profits to be made in running the country as a private corporation formed the Samana Bay Company and offered Howe a handsome salary to sit on the board of directors. Fortunately, the scheme fell apart and to his credit, Howe admitted that he had been lured by the temptation of wealth into a sordid enterprise.

The period following the Civil War brought a rapid increase in the U.S. population, strained government budgets, and fostered pessimistic attitudes about the possibility for educational reform. Many of the institutions for people with special needs which Howe and others had labored to establish became under-funded and began to resemble the old institutions the reformers had worked to replace. Dorothea Dix withdrew from public life and refused to be interviewed about her work.

Howe pushed forward. Known for supporting institutions serving those with special needs, he surprised many in 1866 by declaring that “such persons spring up sporadically in the community, and they should be kept (in the community).” He proposed a cottage system for the Perkins Institute in which students of varying ages would live together in a family like setting, to minimize the effects of institutional life. The trustees thought this might be accomplished elsewhere, away from the city, but Howe argued that the school’s downtown location gave the students access to music performances, a variety of churches, and more opportunities to have others visit them. The cottage system was implemented in 1870.

Howe’s dismay over his wife’s ministry softened as he got older. He grudgingly approved when Julia took to the pulpit. Acknowledging his marital misdeeds brought some reconciliation with Julia. The biography Julia wrote, Memoir of Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, (1876) came out a few months after his death. An homage to his good character and accomplishments it made no mention of any familial strife.

Julia lived for another 34 years. She continued speaking out, organizing, and championing human and women’s rights.

The Samuel Gridley Howe Collection at the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Massachusetts holds an extensive collection of clippings, published and unpublished manuscripts, personal papers, correspondence, books, and related family materials. Additional correspondence, memorabilia, manuscripts, and other papers by and about Samuel Gridley Howe, Julia Ward Howe, and their children are in The Howe Family Papers of the Houghton Library at Harvard University. Additional papers related to Julia Ward Howe are at the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Lamson Family Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts contain additional letters and papers related to Mary Swift and Laura Bridgeman. Dozens of Howe’s addresses, commission reports, letters, patient reports, text books, and Perkins Institution annual and special reports have been published including; The Blind Child’s First Book (1838), An Historical Sketch of the Greek Revolution (1848), Dr. Howe’s Report on the Case of Laura Bridgeman (1834), Insanity in Massachusetts (1834), An address delivered at the anniversary celebration of the Boston Phrenological Society (1836), and The Causes and Prevention of Idiocy (1874). Many of these publications are 10-20 pages long. Consult WorldCat.org for an extensive list of titles or access them on-line at HathiTrust.org or Google Books.

A comprehensive biography from primary sources is found in James W. Trent Jr., The Manliest Man: Samuel G. Howe and the Contours of Nineteenth-Century American Reform (2013). An extensive bibliography can also be found in The Manliest Man. Alternative views of the Howe-Bridgeman relationship can be found in Elizabeth Glitter, The Imprisoned Guest: Samuel Howe and Laura Bridgman (2001) and Mary Swift Lamson, The Life and Education of Laura Bridgman (1878). Older biographies that are useful include; Mark Allen Peterson Crusading against Idiocy: Samuel Gridley Howe, Romantic Reform, and Mental Retardation, 1825-1875 (1983); Katharine E. Wilke and Elizabeth R. Moselve, Teacher of the Blind, Samuel Gridley Howe (1965); Milton Meltzer, A Light in the Dark: The Life of Samuel Gridley Howe (1964); and Harold Schwartz, Samuel Gridley Howe: Social Reformer (1956). A short first hand account of Howe’s life can be found in James Freeman Clarke, “The Chivalry of To-Day,” in Memorial and Biographical Sketches (1878). A book length biography by a contemporary is found in Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, Dr. S. G. Howe: The Philanthropist (1891). Biographies and other volumes by family members tend toward hagiography; these include Laura E. Richards, Samuel Gridley Howe (1935), Laura E. Richards, Letters and journals of Samuel Gridley Howe: Vol 1 & 2 (1906-09), and Laura E. Richards, Two noble lives: Samuel Gridley Howe & Julia Ward Howe (1911).

Useful secondary sources include Peggy A. Russo and Paul Finkelman, eds. Terrible Swift Sword: The Legacy of John Brown (2005), and Dan McKanan, Prophetic Encounters: Religion and the American Radical Tradition (2011). W.E.B. DuBois, John Brown (1909), Edward Renehan, The Secret Six: The True Story of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown (1995), Ernest Freeberg, The Education of Laura Bridgman: The First Deaf and Blind Person to Learn Language (2001), Valarie H. Ziegler, Diva Julia: The Public Romance and Private Agony of Julia Ward Howe (2003), and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Life Upon These Shores: Looking at African American History, 1513-2008 (2011).

Article by John N. Marsh

Posted November 28, 2013