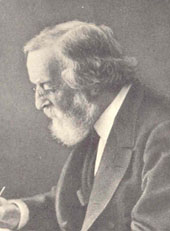

James Freeman Clarke (April 8, 1810-June 8, 1888), an influential Unitarian minister, social reformer, popular author, scholar, and institutionalist, founded and ministered to a new kind of Unitarian church and helped to expand the identity, scope, and influence of nineteenth-century Unitarianism. He was a pioneer in the field of comparative religion, as well as in educational reform. Although he is not now as well known as his friends Ralph Waldo Emerson and Theodore Parker, in his lifetime they were peers.

Born in Hanover, New Hampshire, James was the third of six children born to Samuel Clarke and Rebecca Hull Clarke. Samuel’s mother, Martha Curtis Clarke, was widowed when Samuel was but a year old, and later married the Reverend James Freeman of Boston’s King’s Chapel. Before James’s birth, Samuel had been a merchant and a farmer, but having failed at those occupations he studied medicine at Dartmouth and became a pharmacist.

The Clarke family lived for a short time with the Freemans in Newton, Massachusetts, and when they moved into their own home in Boston, James stayed with his grandparents. His grandfather Freeman tutored him every morning in his study, always taking his cues for the day’s instruction from the boy’s questions about whatever had sparked his curiosity. James made good progress in Latin, Greek, and mathematics. Allowed unlimited access to Freeman’s considerable library, he read British literature and theology and made a start at mastering modern Romance languages.

At age ten James moved into his parents’ home in Boston. He attended Boston Latin School, 1820-25, and Harvard College, 1825-29. Among his classmates were William Henry Channing and Oliver Wendell Holmes. At both schools, classes consisted entirely of the students’ rote recitation of passages of texts in answer to the teachers’ questions. Clarke’s hatred of those dull classes fuelled his later work for educational reform. For a brief time he considered a law career. Then, under the spell of Samuel Taylor Coleridge who had inspired the Transcendentalists, and with his grandfather Freeman’s influence and financial support, he settled on the Unitarian ministry.

Clarke studied at Harvard Divinity School, 1829-33. There he read widely beyond the traditional curriculum, especially in the writings of the German-inspired Transcendentalists. In the spring of 1830, long discussions with his distant cousin Margaret Fuller contributed to their mutual intellectual maturation.

Toward the end of 1830, after his older brother Sam suffered a paralyzing case of rheumatism, Clarke took a year off from seminary to teach at the Cambridgeport Private Grammar School, using the money he earned to help his mother. During that year his father died suddenly. Meanwhile Clarke had continued studying on his own, reading Goethe and other German philosophers. From Goethe, Clarke adopted his personal motto, “Do your nearest duty.”

Eager to see Unitarianism spread to what was then the West, Clarke applied to the Boston Unitarian Ministers’ Council for fellowship as an “evangelist.” He was ordained in 1833 at the Second Church in Boston and accepted an appointment in Louisville, Kentucky.

Clarke’s autobiography describes the sophisticated Boston-educated young minister’s struggles to function in the raw river town of Louisville—with its muddy, unpaved streets, its rowdy, hard-drinking riverboat gamblers, and its unlettered farm families in town to market their produce. The members of Clarke’s Louisville church were chiefly transplanted New Englanders, and they probably would have been pleased, he realized years later, had he simply revised William Ellery Channing‘s published sermons for their hearing. All Clarke knew then was that his considerable learning seemed irrelevant to the lives of these people. Desperately searching for something to say from the pulpit, he began to read sermons printed in the magazines of other churches. He was surprised to find in them much positive and practical Christianity, needing only some adjustment of language to be entirely appropriate in his own church. Thus began Clarke’s later vastly expanded study of other faiths. This experience early in his ministry was also the root of his life-long and recognized ability to mediate between religious traditionalists and free thinkers.

With his friend the Cincinnati minister Ephraim Peabody, Clarke founded a Unitarian magazine, The Western Messenger, which carried literature and theological commentary intended to aid the spread of liberal Christianity in the West. It was originally edited and printed in Cincinnati by Peabody, with Clarke writing many of the articles and soliciting others from friends in the East. In 1836 Clarke took over as editor.

In 1837, Clarke went to Meadville, Pennsylvania to visit Harm Jan Huidekoper who had endowed a liberal Christian seminary there. He fell in love with Huidekoper’s daughter Anna, and in 1839 they married and eventually had four children. In 1840, Clarke resigned his Louisville ministry. He and Anna moved in with the Huidekopers in Meadville for a year while they planned the future. During that year Clarke took on no regular ministry, but he was a guest preacher in pulpits throughout the region and helped to establish the first Unitarian church in Chicago.

Clarke had become convinced that Unitarian churches—still largely a New England phenomenon and still largely established there in the parish pattern of Colonial days—would soon die out unless Unitarian ministers and members learned to re-organize church life to meet the changing demographic and social realities of western American life. He could never change the deeply entrenched customs by argument, so he would have to lead by example, creating a new kind of Unitarian church.

In 1841, James, Anna, and their firstborn son Herman moved to Boston. Clarke set about gathering a church, the first Unitarian church in New England not geographically based but drawing members from all over the city. The church would be classically Unitarian: Christian in ethos, open to reason and other sources of truth, and committed to positive engagement with the world’s social problems.

Clarke’s years of biblical study had brought him to see Jesus as both a conservative and a reformer, not replacing the Law but fulfilling it, and the divinely inspired religion of Jesus not only as compatible with reason but as the very rational foundation of science. To Clarke the life and teachings of Jesus Christ embodied and affirmed what was best in other world religions. Or, to put that differently, Clarke saw his saw his own liberal Christian “intuitions” reflected transcendentally in the religious experiences of the whole human race. In this vein, Clarke remained all his life a Transcendalist, but he rejected that label when Transcendentalists like his friends Emerson and Parker denied the need for historical precedents, as though they could have the religion of Jesus without Jesus.

In accord with the always reforming left-wing of the Protestant tradition, Clarke aimed to gather “a true church of disciples.” He formulated three key principles of such a church—the social, the voluntary, and the congregational. Socially, members should make strong interpersonal connections, and gather not just for worship but in committees and study groups to further the church’s purpose. Members should voluntarily regard themselves as equals in the church and voluntarily assume stewardship of the community, supporting it with their financial pledges and offerings. And congregational worship, like the church’s other activities and property, should be common to all, with the congregation singing hymns, reading and praying responsively, and even sharing in the preaching. The order of service Clarke developed was ecumenical: he drew on Quaker-inspired silence and meditation, Catholic-inspired holy days, and Methodist-inspired lay singing and preaching.

In 1841, Clarke gathered a church steering committee. Then he preached a series of three sermons in Boston’s Swedenborg Chapel, titled “The Essentials of Christianity,” “Justification by Faith” and “The Church as It Was, Ought to Be, and Can Be.” On all three nights the chapel was filled to overflowing. Clarke then met with a group of interested laypersons. He offered to minister to them with the theology and principles he had outlined. They agreed. They secured Armory Hall, and later the Masonic Temple, for Sunday morning and evening services. The members drew up a simple pledge of faith in Jesus Christ, and united as a Church of his Disciples to study and practice Christianity. Some one hundred signed the book as members, but many others participated in church activities. By 1845, regular attendance at Sunday worship was about seven hundred. In 1848 the congregation built a meetinghouse.

As Clarke had envisioned they should, the members formed many committees. A Pastoral Committee determined church policy. A Youth Committee supervised the Sunday school. A Benevolent Action Committee directed church charity. A Music Committee planned hymn-singing. Each Wednesday, social meetings addressed a wide range of topics, including philosophy, politics, morality, new books, and current events. If there was no social meeting, there was a Wednesday prayer meeting. Weekly Bible classes for men and women were offered in private homes, often led by lay members. The church contributed to charities, such as the Boston Port Society, and the church’s women established their own charitable society for poor and underprivileged women.

By 1845, and despite much criticism from Boston’s Unitarian clergy, the Church of the Disciples was strong enough to weather a crisis. Following Theodore Parker’s controversial 1841 sermon “The Transient and Permanent in Christianity,” most Unitarian ministers refused to exchange pulpits with him. When Clarke invited Parker into his pulpit, sixteen members resigned in protest. Other members made up for the loss, however, and even the dissidents remained friendly.

In 1844, Clarke was named chaplain to the Massachusetts Senate. In 1845, he was elected to the Executive Board of the American Unitarian Association and made Director of the Home and Foreign Missionary Board. Clarke wrote over two hundred articles and poems for his church’s weekly newsletter, entitled The Christian World. He also gathered and published the orders of service and hymns used by the church. Beginning in the 1840s, Clarke participated in many movements for social reform—for temperance, woman’s suffrage, educational reform, prison reform, peace, and unions, and against the death penalty and slavery.

Worn out from overwork and grieving the early death of his son Herman, in 1849 Clarke was granted a summer sabbatical for his health. He traveled in Europe, but without lasting benefit. In the winter of 1850 he contracted typhoid and was incapacitated for half the year. When he recovered, his doctor prescribed rest and abstinence from church work. The Church of the Disciples went into decline, and on Clarke’s advice they sold their meetinghouse. Clarke took a three-year break from his Boston pastorate, living again with the Huidekopers in Meadville and spending more time with his family. He studied “ethnic religions” and lectured on them at Meadville Theological School, and he also served as assistant pastor for two years at the Meadville church.

In 1853, Clarke returned to his pastorate of the Church of the Disciples in Boston, re-gathering the flock and resuming his former schedule of preaching, Sunday school, parish calls, and evening meetings. In 1855 he purchased Brook Farm, hoping to resuscitate communal living there with friends, but it proved too far from Boston, and so the Clarkes settled in Jamaica Plain. In addition to resuming his pastorate, Clarke took up other activities. He served on the Jamaica Plain School Committee and worked briefly with Parker to revive the meetings of the Transcendental Club. He attended meetings of the Boston Ministers’ Association and advised the American Unitarian Association on expansion, the “broad church” question, missionary work, and how to garner more support for that work from the churches. Clarke served as Secretary (head of staff) of the AUA, 1859-61.

In 1836 Clarke had reviewed Channing’s book on slavery for the Messenger. Many of his slaveholding parishioners and friends in Louisville had treated their slaves kindly and were themselves critical of slavery. Hence Clarke tended to agree with Channing that the slave system—not slaveholders—should be condemned and that immediate emancipation would be impractical. Later Clarke preached more zealously against slavery, and in 1845 he drafted a letter (signed by 173 other Unitarian ministers) protesting slavery as a violation of the principles of Unitarian faith.

Clarke dreaded the coming of the Civil War, but he came to see it as the redeeming work of God, chastising the Nation and purging it of the evil of slavery. He was pleased when President Lincoln linked the War to emancipation. Clarke offered Brook Farm to the Union army as a training ground for soldiers. He visited and preached at Union camps and labored to raise funds for Henry Whitney Bellows‘s American Sanitary Commission—organized to meet the needs of the wounded. During and after the War, the Disciples sent teachers and supplies to help the freed slaves through Edward Everett Hale’s New England Educational Commission.

From 1863-69, Clarke served on the Massachusetts State Board of Education. In 1867 he was appointed to the faculty of Harvard Divinity School as “Professor of Natural Theology and Christian Doctrine,” and later as “Professor of Ethnic Religions and the Creeds of Christendom.” All of Clarke’s courses—on comparative theology, Christian doctrine, Roman Catholicism, and the Apostle Paul—were known for their lively classroom discussion. His teaching method, revolutionary at the time, was to ask the students questions about their assigned reading. After listening respectfully to all of their answers, he briefly summarized their differing points on the issues and offered his own position at the end of class.

Beginning in 1866, Clarke served as a member of the Harvard University Board of Overseers. He envisioned the Divinity School as a “university of theology,” with every important Christian denomination represented there by someone who would state its views on its own terms. He also influenced the School to offer attention to non-Christian religions. As for the College, he recommended an end to ancient language requirements and more emphasis on modern languages and literature. In 1872 he urged, though unsuccessfully, the admission of women.

Clarke was twice invited to give lectures at the Lowell Institute based on his twenty-five years of research and thought on comparative religion. These lectures were published as Ten Great Religions (2 volumes), 1871 and 1883, and Events and Epochs in Religious History, 1881. Clarke pictured the various religions, “in reference to universal or absolute religion,” arranged on an evolutionary scale. While non-Christian or “ethnic” religions were “arrested” and “partial” according to Clarke, Christianity was “progressive” and “universal.” He thought that Christianity alone had the power to “reconcile antagonist truths and opposing tendencies,” overcome social evils, promote democracy, reconcile humanity with God, and grow into a universal religion. Since the object of his new discipline was to prepare the way for this universal religion, it was, he believed, “the science of missions.” That any non-Christian religion could be considered to possess even partial or subordinate truth, however, was in Clarke’s time a radical departure.

In his later years, Clarke was increasingly disturbed by the social dislocation resulting from the rapid rise of American urban industrialization. He worked in movements to ameliorate the effects of poorly managed immigration, inadequate housing, alcoholism, and economic and political corruption. Yet he was also awed and excited by the many benefits of modernization, as those he witnessed in transportation, entertainment, and communication.

When his friend Henry Whitney Bellows began to urge the formation of the National Conference of Unitarian and Other Christian Churches, Clarke readily lent his prestige to the undertaking. He stressed as he always had the possibility of ecumenical cooperation in Christian work, and he never ceased trying to mediate between the Christian Unitarians and the free religionists.

In a sermon printed in his Vexed Questions in Theology, 1886, Clarke revised the five points of Calvinism into the influential “Five Points of the New Theology.” These were later made notorious as the overly-optimistic Unitarian affirmation of belief in “the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, the leadership of Jesus, salvation by character, and the continuity of human development in all worlds, or, the progress of mankind onward and upward forever.”

In his eighth decade Clarke’s heath was generally good. He remained active, working hard but also taking time for recreation and spending summers at a family cottage. In 1882 he took a trip to Europe. Beginning in the winter of 1886-87, however, he experienced increasing fatigue. He preached for the last time in May of 1888, and he died peacefully, his family around him, less than a month later.

Sources

The James Freeman Clarke Papers, consisting of letters, lectures, and records from the Church of the Disciples; microfilms of selected letters and The Western Messenger; and letters from the American Unitarian Association Letterbooks are kept in the Andover-Harvard Theological Library at Harvard Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There are also Clarke letters in various collections in other libraries at Harvard, and at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts. His letters to Fuller, edited by John Wesley Thomas, were published as Letters of James Freeman Clarke to Margaret Fuller (1957). His sermons, 1873-88, were printed in The Boston Saturday Evening Gazette. In addition to The Western Messenger and The Christian World, Clarke also edited the Monthly Journal of the American Unitarian Association. He wrote prolifically for many periodicals, including The Christian Examiner, The Christian Inquirer, The Christian Register, The Dial, Harper’s, The Index, and Atlantic Monthly. He wrote and published many sermons, speeches, essays, tracts, books, hymnals, and liturgies. Among his books not mentioned in the biography above are Common-Sense in Religion (1874); Self-Culture: Physical, Intellectual, Moral, and Spiritual (1880); Memorial and Biographical Sketches (1880), containing chapters on William Ellery Channing, Theodore Parker, Samuel Gridley Howe, Walter Channing, Ezra Stiles Gannett, Samuel J. May, James Freeman, and Charles Sumner; and Anti-Slavery Days (1884). He was an editor and contributor to The Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli (1852), and wrote his own Autobiography, Diary, and Correspondence (1891). The principal biography is Arthur S. Bolster, Jr., James Freeman Clarke, Disciple to Advancing Truth (1954). There is an article on Clarke by David Robinson in American National Biography (1999).

Article by Gregory McGonigle

Posted September 23, 2002