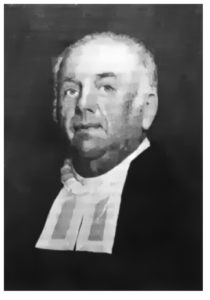

William Bentley (June 22, 1759 -December 29, 1819), the minister of the East Church in Salem, Massachusetts, was one of the first New England ministers to openly profess Unitarian beliefs. Never married, he devoted his life to his congregation and to his work as a scholar, book collector, linguist, newspaper journalist, and author. His extensive diary entries reward readers with a portrait of Salem and Boston life from the Revolutionary War until his death. A leading American Enlightenment thinker, Bentley was a close friend of James Freeman, the first preacher in America to call himself a Unitarian. Both were in correspondence with British Unitarians at the beginning of the nineteeth-century.

Born in Boston to Elizabeth (Paine) and Joshua Bentley, a ship carpenter, he was named for his mother’s father. As a youngster he lived with that grandfather, William Paine, a well-to-do miller and landowner. At age six he was enrolled at the North Writing School where he studied Greek and Latin. Boston Latin School followed.

Born in Boston to Elizabeth (Paine) and Joshua Bentley, a ship carpenter, he was named for his mother’s father. As a youngster he lived with that grandfather, William Paine, a well-to-do miller and landowner. At age six he was enrolled at the North Writing School where he studied Greek and Latin. Boston Latin School followed.

When he was fourteen, his grandfather enrolled him at Harvard College. At the time, Harvard consisted of a half-dozen buildings. Bentley studied under Stephen Sewall, Hancock Professor of Oriental (both near & far east) Languages. Sewall, an expert in philology and linguistics, was one of the first Harvard faculty members to stress scholarship and analysis over recitation and memorization. James Freeman, a classmate, became a lifelong friend.

During the Revolutionary War, his father Joshua and his brother John worked as army clerks in a munitions warehouse on the Boston commons. Another brother, Joshua Jr., was captured and died while Bentley was in college. In 1775 when colonial troops occupied the Cambridge campus, William Bentley along with other students and faculty were evacuated to Concord. In 1777 he graduated from Harvard with an AB and high honors.

For the next three years, he taught school in Boston, first at Boston Latin and then at the North Grammar School. While he taught he also pursued graduate studies at Harvard, which in 1780 awarded him an AM and then appointed him as a Latin and Greek tutor, a position he held until 1783. In addition to these duties, he was occasionally called to preach at nearby churches.

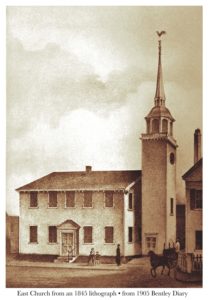

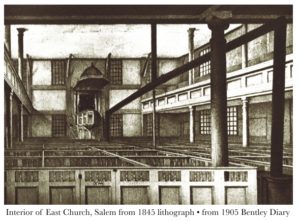

In May 1783 Bentley was invited by Salem’s East Church to candidate for the position of assistant pastor. Their pastor of 47 years, James Diman, a Calvinist, opposed the selection of Bentley. After preaching for four months, Bentley was formally called by the congregation. His ordination took place September 24 with John Lathrop (a man of Arminian beliefs), the minister of Boston’s Second Church, delivering the sermon. The dual pastorate lasted for two years, but it was not harmonious. Bentley could preach on Sunday morning, but Diman refused to let him serve communion or baptize children.

The East Church flock was made up of sailors and ship captains, merchants and artisans, young folks and widows. They preferred Bentley’s broad interpretation of eligibility for communion and baptism over Diman’s strict rules. A high proportion of church members were women, but they couldn’t vote. Decisions at East Church were in the hands of the pew proprietors, two-thirds of them ship captains who had grown wealthy from privateering during the Revolutionary War and from expanded world trade—free of British restrictions—afterwards. These captains and seamen were world-travelers who traded in India, China, Africa, South America, Europe, Caribbean islands, and the East Indies. Among the goods imported and resold at profit were pepper, sugar, molasses, and tea. Some engaged in opium and slave trading, even some members of Bentley’s congregation.

The East Church flock was made up of sailors and ship captains, merchants and artisans, young folks and widows. They preferred Bentley’s broad interpretation of eligibility for communion and baptism over Diman’s strict rules. A high proportion of church members were women, but they couldn’t vote. Decisions at East Church were in the hands of the pew proprietors, two-thirds of them ship captains who had grown wealthy from privateering during the Revolutionary War and from expanded world trade—free of British restrictions—afterwards. These captains and seamen were world-travelers who traded in India, China, Africa, South America, Europe, Caribbean islands, and the East Indies. Among the goods imported and resold at profit were pepper, sugar, molasses, and tea. Some engaged in opium and slave trading, even some members of Bentley’s congregation.

Salem, one of the ten largest urban centers in America, had a population around 8,000 (Boston’s was 18,000). Most of Salem’s “old money” citizens were members of the North Church under Thomas Barnard, Jr. or First Church under minister John Prince. Challenged by the growth of emotional and evangelical sects, these “standing order” or town-supported churches and congregations were moving away from the strict Calvinism of the Puritans toward more liberal Arminian beliefs. Liberal, in this case, means those who tended to believe they could overcome immorality and earn God’s forgiveness—in contrast to Calvinists—praying for God’s grace to overcome depravity. Paraphrasing Alexander Pope, Bentley summarized these beliefs in his diary; “The only evidence I wish to have of my integrity is a good life, & as to faith, his can’t be wrong whose life is in the right.”

Bentley kept a diary all his life. He started it on April 30, 1784 writing; “Arrived at Beverly Capt. George Dodge, after sickness and a long Voiage to the W. Indies.” He discussed anything and everything he saw, read, or learned. The entries followed the same principle as his daily walks where it was remembered that he “noticed every change going on.” About three-fifths of these hand-written manuscripts have been published as The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Vol. 1-4 (1905 to 1914). His diaries contain his observations about philosophy, theology, people, the world of politics, all categories of scientific development as well as statistical tables, books, deaths, births, marriages, shipping news, the weather and, of course, Salem gossip plus other trivia. But surprisingly very little “self contemplation.”

While his diary entries were private, his newspaper columns were public and thereby meant to educate his readers in the immediate Salem vicinity to his ideals and ideas. Bentley’s twice-weekly news digests were published regularly in the Salem Gazette, the Essex Register, and the Essex Gazette. Indeed, they often reached a larger public too, as a number of them were reprinted by other journals. One reason for this was that his news summaries included events and stories not easily available to those who devoured these local newspapers. This was especially true for his reporting of European military and political events. His ability to read and understand twenty languages also made it possible for him to translate articles appearing in foreign journals. Indeed, his language skill was even of assistance to the Federal government. When Albert Gallatin, Jefferson’s Secretary of State needed someone to translate the credentials of the Tunisian ambassador to Washington, he asked Bentley.

Not long after Bentley started at the East Church, he met William Hazlitt Senior. Hazlitt and his five-year old son came to America in 1783 (the son, also named William Hazlitt, grew up to become the famous British literary critic). Arriving at the end of the Revolutionary War, they spent a year in New York City and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania before Hazlitt Sr. visited Boston and preached at the Brattle Street Church. In 1784 he met with the Boston Association of Ministers, visited James Freeman the reader at King’s Chapel in Boston, and preached at Bentley’s church. Under Hazlitt’s influence, Bentley moved away from his Arian beliefs toward the Socinian Unitarianism of the British Unitarians. Over the next few years the British Unitarians sent offprints of sermons and Unitarian tracts by Joseph Priestley and Theophilus Lindsey to Freeman in Boston. James Freeman shared the tracts with Bentley and other sympathetic Americans. In return, Freeman kept the English Unitarians informed on developments and progress in America.

Bentley developed a “Socinian” catechism in 1785 for use in his church based on one written by Joseph Priestley. There was nothing in it about the divinity of Jesus. Cautious, Bentley couched his Biblical interpretations as nothing more than corrections to previous translation errors. It prized morality and good works over Calvinist grace and faith.

In 1785 he opened baptism to all children even though the parents had not made a profession of faith. None of the other Congregational ministers followed his lead. In a unanimous vote (except for Diman), the congregation sided with Bentley and ruled, “all baptized persons shall obtain baptism for their children.” In October 1785, Diman finally resigned making Bentley sole pastor. Diman continued to live in the parsonage until he passed away three years later. Timid and ineffectual as a suitor, Bentley settled into a comfortable single life. With Diman in the parsonage, Bentley took a local room. From 1791 until his death in 1819, he was a boarder with Mrs. Hannah Carlton Crowninshield, a widow.

Liberal Congregationalists tended to elide questions about beliefs and labels. One of the first signs of the growing acceptance of these liberal beliefs was the publication of the hymnbook, Collection of Hymns — designed for the use of the West Society of Boston (1783). Bentley liked choral music, so he organized, taught, and directed choirs. He soon produced his own hymnbook, A Collection of Psalms and Hymns, for Publick Worship (1788). It reflected the liberal and catholic spirit that characterized his preaching and the views of the congregation.

An individual of routine he wrote his two weekly sermons on Monday, composing them at a stand up desk where he did all of his writing, much of it before sunrise. Dartmouth College, recognized Bentley’s talents and awarded him an honorary AM in 1787.

An individual of routine he wrote his two weekly sermons on Monday, composing them at a stand up desk where he did all of his writing, much of it before sunrise. Dartmouth College, recognized Bentley’s talents and awarded him an honorary AM in 1787.

In late 1788, Bentley noted in his diary that he had refused an invitation to attend John Murray’s ordination because he didn’t want to lend his name to, “an illiterate foreigner without credentials.” Even though he showed little respect for John Murray, he was curious to learn more about his message. In 1888, Bentley attended Mr. Freeman’s Christmas morning service and the Universalist afternoon service where he heard “The mountebank preacher J. Murray,” who, “prayed in the incomprehensible language of Relly.” Commenting on Universalism in 1805, Bentley said, “But if superstition takes away fear of evil, & confounds the notions of personal virtue as essential to character, it does all theory can do, to deprave the understanding & corrupt the heart.”

Bentley felt his own faith was a search for truth based on reasoning and knowledge. In a diary entry dated April 22, 1788, he says, “I have adopted many opinions abhorrent of my early prejudices, & am still ready to receive truth upon proper evidence from whatever quarter it may come.” For Bentley, intellect trumped emotion. His entry continues, “I think more honor done to God in rejecting Xtianity itself in obedience to my convictions, that in any ferver, which is pretended, towards it, & I hope that, no poverty which I can dread, or hope I can entertain, will weaken my resolutions to act upon my convictions.”

Bentley frequently visited James Freeman when he traveled to nearby Boston. In 1788 they exchanged pulpits for the first time. In a 1790 sermon he delivered from Freeman’s pulpit, he said “When a man is found, who does not profess much, nor despise all, who is pure from guile, peaceable in his life, gentle in his manners, easily dissuaded from revenge, with a heart to pity and relieve the miserable, impartial in his judgement, and without dissimulation, this is the man of religion.” Bentley went on to conclude that “This is an apostolic description of a good man; and whatever opinions he may have, he ought to have some, and he has a right to choose for himself; this man is after God’s own heart.”

Both Bentley and Freeman served on the Massachusetts Historical Society board. In a 1796 diary entry Bentley noted, “Brother Freeman told me that he had received 500 dollars toward printing Unitarian Books & that he proposed to begin with Priestley’s Corruptions.” In a 1792 diary entry, he notes that he “. . . dined with Mr Freeman. Paid to him the sum of five dollars, my subscription towards the Unitarian Society in Portland [Maine], now supplied by Mr. Oxnard.” Joseph Priestley presented Bentley with a copy of his Discourses relating to The Evidences of Revealed Religion, when it was published in Philadelphia in 1796.

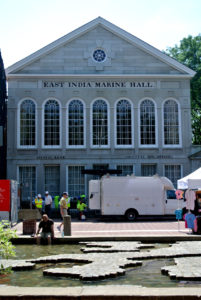

Bentley mentored several promising future leaders, especially Nathaniel Bowditch one of the first scientists in the new republic. He encouraged Bowditch to study Latin and lent him books from his library, including Isaac Newton’s Principia. After Bentley joined the Salem Philosophical Library—by purchasing Dr. Joseph Orne’s membership rights—Bentley and John Prince urged the library to grant borrowing privileges to 18-year old Bowditch. In 1794, Bowditch assisted Reverend Bentley and shipmaster John Gibaut in a survey of Salem and its harbor. Bentley also assisted in the formation of the “Salem East India Marine Society” (est. 1799) and served as its unofficial chaplain.

Bentley’s personal library, one of the largest in America, contained over 2,000 titles (4,000 volumes). Thomas Jefferson was so impressed with Bentley’s library, his command of languages, his intelligence, and his Jeffersonian political views that in 1805 he offered Bentley the presidency of the college he was founding, the University of Virginia. Bentley, who preferred to remain true to his ministerial calling, rejected it declaring; “He had been long wedded to the East Church, he could not think of asking a Divorce from it.” He also turned down a later invitation to become the Chaplain of Congress.

Bentley’s personal library, one of the largest in America, contained over 2,000 titles (4,000 volumes). Thomas Jefferson was so impressed with Bentley’s library, his command of languages, his intelligence, and his Jeffersonian political views that in 1805 he offered Bentley the presidency of the college he was founding, the University of Virginia. Bentley, who preferred to remain true to his ministerial calling, rejected it declaring; “He had been long wedded to the East Church, he could not think of asking a Divorce from it.” He also turned down a later invitation to become the Chaplain of Congress.

As the Revolutionary War faded into the past replaced by newer conflicts, conservative or reactionary voices grew stronger in the newly formed United States. Jedidiah Morse might have had Bentley in mind when he denounced the “French revolutionaries, atheistic Freemasons, and the Illuminati conspirators” in a 1798 sermon. Morse was a self-appointed defender of the faith for New England’s Standing Order churches. Opposed to liberals, Unitarians, and Socinians, he opposed the appointment of Henry Ware to the Hollis Chair of Divinity at Harvard in 1804. The following year Morse started his own journal, The Panoplist to expand his attacks.

Liberal Congregationalists developed their own periodicals to respond and defend themselves. This back and forth debate was carried on in a succession of publications; The Monthly Anthology and Boston Review, the General Repository and Review, the Christian Disciple & Theological Review, and the Christian Examiner and General Review. Bentley didn’t participate in the exchange but he did get attacked by both sides.

The liberal periodicals were critical of Bentley, probably because his Socinian beliefs went too far and his political beliefs were Republican at a time when most of New England’s leaders were Federalists. The Monthly Anthology and Boston Review, a liberal periodical, nitpicked Bentley’s choice of words and his biblical interpretations in the sermon he delivered before the Massachusetts Governor and legislature in 1807:

We would willingly, for our own amusement, and for that of the publick, make more remarks on this performance, which the author courteously styles a sermon, did not its remaining obscurity set all further criticism at defiance. We would recommend it however to the attention of all those ingenious ladies and gentlemen, who are fond of riddles, enigmas, and conundrums, humbly acknowledging our utter inability to comprehend it, and firmly believing, notwithstanding the author is minister of the second church in Salem, that he will never be hanged for a witch.

This split among New England Congregationalists came to be called “The Unitarian Controversy.” In 1815, Jedidiah Morse published American Unitarianism, a reprint of chapter nine of the 1812 British book by Thomas Belsham, Memoirs of the Late Theophilus Lindsey. That ninth chapter was based on letters and progress reports that James Freeman had been sending to the British Unitarians. Candid and overly optimistic, Freeman probably wrote his letters hoping to elicit more support from the English, never thinking the letters might be published. Once public, they widened the split. A review of that chapter in Jedediah Morse’s The Panoplist charged New England’s liberal ministers with secretly sharing Lindsey’s Socinian views, although hiding them from their own church members.

During the years when American Unitarianism was blossoming, Bentley’s minority Socinian position was fading in importance. His contribution to the movement was limited and he was isolated from its leaders. He was older, he didn’t participate in theological arguments, and he didn’t participate in the disputes in the new periodicals. Another cause of his marginalization was his expressed belief that most of his colleagues lacked the education and knowledge that he regarded as an essential source of the new republic’s vitality. Historians agree that Bentley embraced Socinian Unitarianism while at the same time denying the truth of biblical revelation, especially Christ’s miracles and resurrection. Socinian Unitarians—like Bentley—saw Jesus as human,whereas conservative Calvinists claimed that Jesus was an element of the triune God. The liberal Congregationalists stood somewhere in between.

Bentley regularly corresponded with between 400-600 individuals. Among those he was in touch with were Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Joseph Priestley, and Professor Christoph Daniel Ebeling, professor of history and Greek at the Hamburg Academic Gymnasium, librarian of the Hamburg Public Library, and author of a seven volume geography and history of North America.

As an independent scholar, Bentley was active in a number of scholarly organizations. He was a member and contributor to the work of the American Antiquarian Society where he served as a Councilor until his death. He was also a member of the American Philosophical Society and the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS). The MHS published a draft of his unfinished but helpful history of Salem in its Historical Collections (1799). On the local level, Bentley was a member of the Salem School Committee and sometime schoolteacher for the town, active in the local militia, the Union Fire Club, the East India Marine Society, and the Freemasons. He also supported the work of the Salem Female Charitable Society.

Bentley held and preached the prejudices of his time. While he was growing up in his grandfather William Paine’s home he was served by slaves. The Salem community was supposed to care for its own poor, sick, lame, and unemployed, but they didn’t extend this charity to strangers from other towns. Bentley reports in his diary, with approval, that a group of “vagabonds” were “warned out,” carted out of town in a “large wooden cage.” When Salem “warned out” most of its black citizens, he remained silent. On the other hand, when Prince Hall, Master of the African Masonic Lodge, was having trouble writing Masonic Charges, Bentley came to his assistance. There are a number of condescending comments in Bentley’s diary about the lower classes and the less educated. He was something of a snob toward his intellectual inferiors. He could confide his distaste for slavery in his diary but was careful not to mention it in public.

Bentley’s wide knowledge of the world came from his network of neighbors and friends; many who traveled and traded around the world. He was often out and about in Boston and other Massachusetts towns, but he only traveled to two nearby New England states. His life style was simple and his “parsonage” for thirty years was the room he rented from the widow Hannah Carlton Crowninshield. Today that residence, which was moved from its original location, is known as the Crowninshield-Bentley House. Owned by the Peabody-Essex Museum the public can visit his restored bedroom and study.

Bentley’s wide knowledge of the world came from his network of neighbors and friends; many who traveled and traded around the world. He was often out and about in Boston and other Massachusetts towns, but he only traveled to two nearby New England states. His life style was simple and his “parsonage” for thirty years was the room he rented from the widow Hannah Carlton Crowninshield. Today that residence, which was moved from its original location, is known as the Crowninshield-Bentley House. Owned by the Peabody-Essex Museum the public can visit his restored bedroom and study.

Among his flock and within the Salem community, his generosity was well known. He was able to help those in need by keeping—except for book purchases—his expenses low. His assistance to people went far beyond financial help; he helped his Roman Catholic neighbors to celebrate their first Mass in Salem, and he shared his pulpit with ministers from various Protestant denominations who were not usually welcomed by other Congregational clerics.

If Bentley treasured his library, he also valued just as deeply his “Cabinet” or collection of “mementos,” “rare curiosities,” and unusual scientific items many of which were brought to him by his sea-faring friends upon their return from exotic world ports. Included in these artifacts was his impressive and extensive coin collection, one of the first such in America.

Bentley had planned to leave his books and “cabinet” to Harvard, but they postponed granting him an honorary DD until just a few months before his death. Feeling that they had treated him poorly, he changed the instructions to his executor, William Bentley Fowle. Fowle, his nephew was a Boston bookseller. In the end, Bentley’s German books, New England printed books, manuscripts, his “Cabinet,” paintings, and engravings went to the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts. The classic books, theological books, dictionaries, lexicons, and Bibles were given to Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania. Most of the 700 volumes that went to Allegheny were by English divines of the standing order, although a few nonconformists—Samuel Clarke, James Foster, Richard Price, James Gifford, and Joseph Priestley—were included. William Bentley wanted his diaries and manuscripts destroyed, but Fowle did not follow that instruction.

During his last years, Bentley endured heart problems. He was but five feet tall, and for most of his life obese (he weighed over 240 pounds), so this was not surprising.

The last entry in William Bentley’s diary is dated December 29, 1819. In it, he notes that “The Bengal Government have a Board of trade that can give authority to any member to exercise all the powers of the board as circumstances may require.” That evening he attended a large gathering for Captain James Fairfield, a parishioner who had just returned from a long sea voyage. As was his custom, he stopped to say goodnight to his landlady before going to bed. He died that night just after ten o’clock. His funeral was held in his church on January 2, 1820 with the eulogy delivered by the noted orator Edward Everett, then professor of Greek Literature at Harvard and later its president.

The year Bentley died, 1819, was also the year that William Ellery Channing delivered his influential sermon on “Unitarian Christianity” at the ordination of Jared Sparks in Baltimore, Maryland. Channing delineated a middle course between Bentley’s Enlightenment reasoning and Jedidiah Morse’s Christian orthodoxy. It was this middle path that would lead to the formation of the American Unitarian Association (AUA) in 1825.

William Bentley’s diaries, papers, and some sermons (1808-13) are in the collections of the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts. Over 1200 sermons are in the Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. Additional manuscripts can be found in the Special Collections at the Pelletier Library, Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania; the library and archives of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; and the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. For a bibliography of Bentley’s works see J. Rixley Ruffin, A Paradise of Reason (2008). For a listing of the 1200 sermons in the Tufts University Archives see Alan Seaburg, “Sermons of Reverend William Bentley, 1759-1819” (1964). Bentley’s library is cataloged in William Bentley Fowle, “Inventory of the Library of William Bentley,” 1820, in the Bentley Papers at the American Antiquarian Society. Volume One of Bentley’s Diary (1905) has a short bibliography that lists a number of his Masonic discourses and charges. For more on his view of Universalists, see Carl Seaburg, compiler, “Extracts from Bentley, being all those references to Universalism and Universalists found in four volumes of the diary of the Rev. William Bentley of Salem, Massachusetts, from 1786 to 1819,” in the Harvard Divinity School Library.

See the standard history of the period, Conrad Wright The Beginnings of Unitarianism in America (1955) for a comprehensive look at eighteenth-century liberal and Unitarian movements. Wright details the liberal and Arminian beliefs of sixty eighteenth-century New England ministers. J. Rixey Ruffin, A Paradise of Reason: William Bentley and Enlightenment Christianity in the Early Republic (2008) is a comprehensive look at Bentley, including biographical details, macro history of the period, a microhistory of Salem, an exhaustive bibliography, and an extensive discussion of Bentley’s beliefs and theology based on an examination of over one thousand sermons. See also John Ruskin Clark, William Bentley and His Place in the Development of Unitarian Theology, Thesis, Meadville Lombard Theological School (1940). For more on the early development of Unitarianism see William Wallace Fenn, “How the Schism Came,” Unitarian Historical Society Journal (1925) and Samuel A. Eliot, Heralds of a Liberal Faith: The Prophets, (1910). For information on the connections between American ministers and specific British Unitarians see Duncan Wu, William Hazlitt: The First Modern Man (2008) and J. D. Bowers, Joseph Priestley and English Unitarianism in America (2007). Bentley is mentioned in the general Unitarian history of Earl Morse Wilbur, A History of Unitarianism in Transylvania, England and America, (1952). For first hand impressions of early Unitarian clergy see William Buell Sprague, Annals of the American Unitarian Pulpit, (1865).

Posted October 23, 2013