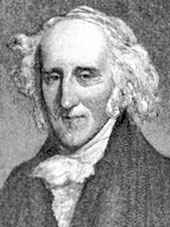

James Freeman (April 22, 1759-November 14, 1835), Minister of King’s Chapel in Boston for 43 years, was the first preacher in America to call himself a Unitarian. Unlike New England liberal Congregationalist ministers, who approached Unitarianism through Arianism, he was Socinian in theology and developed links with Unitarians in England.

Freeman was born to Lois Cobb and Constant Freeman in Charlestown, Massachusetts, just outside of Boston. His father was a sea captain turned merchant. James received his secondary education at the Boston Latin Grammar School, where he studied under the well-known schoolmaster, John Lovell. He attended Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1773-77 and, despite the disruptions caused by the Revolutionary War, for a time afterwards pursued theological studies as a graduate resident.

After graduation Freeman prepared a company of men from Cape Cod for service in the Revolutionary army. In 1780 Freeman chartered a small ship bearing a cartel (a safe-conduct) and took his sister and brother to Quebec to rejoin their father, who lived there at that time. En route he was captured by a privateer and confined in a prison ship in Quebec for several months. He then remained in Quebec on parole until 1782.

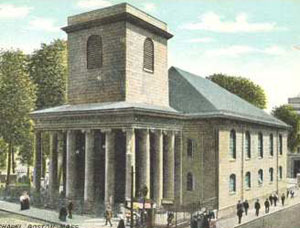

After he had candidated at various Boston pulpits, in 1782 the Episcopalians at King’s Chapel asked Freeman to officiate as their reader for six months. Founded in 1686, King’s Chapel was the first Episcopalian Church in New England. The Rector, Henry Caner, a Loyalist, had been forced to leave in 1776 when the British troops evacuated Boston. After the departure of his assistant a few months later, the Chapel was closed for about a year. In 1777 the Chapel proprietors gave permission to the members of the Old South Church (Congregational), who had been displaced from their own meetinghouse by the British, to worship in King’s Chapel. Because of anti-British sentiment, it was popularly known as Stone Chapel. Before long, the original congregation returned to the Chapel, and the two societies, one Episcopalian and one Congregational, shared the facilities until 1783 when the Old South Church congregation returned to its newly renovated building. Freeman was well liked at Stone Chapel. When his six months were concluded, at Easter 1783, the proprietors asked him to be Pastor of the Church.

Before he accepted the position of Reader at Stone Chapel, he requested that he not have to read the Athanasian Creed. As the Episcopalians were not particularly fond of the creed, the congregation readily consented. After reading Joseph Priestley’s A History of the Corruptions of Christianity (1782) and Theophilus Lindsey’s An Historical View of the State of the Unitarian Doctrine and Worship from the Reformation to our own Times (1783), Freeman began to further doubt the doctrine of the Trinity and became increasingly uncomfortable with the liturgy in the Book of Common Prayer. Having adopted the Socinian Unitarianism of Priestley and Lindsey, he rejected the pre-human existence of Jesus. (Others who were soon to be known as Unitarians, the Arian liberal Congregationalists of New England, accepted the pre-existence of Jesus.) He told his closer friends at the Church that he could not conscientiously perform the service as it stood. He wondered if he should relinquish his position as pastor. One of his friends suggested that he present his dilemma to the congregation, and let them decide.

Beginning in 1784 Freeman preached a series of sermons on the unity of God, stating his dissatisfaction with certain parts of the liturgy, and giving his reasons for rejecting the Trinity. He thought that these would be the last sermons he would ever give there. To his surprise he was heard patiently, attentively, and kindly. He persuaded the Church to alter the liturgy, eliminating all references to the Trinity and addressing all prayers to God the Father. The Chapel was the first church in America to make such changes. On that ground it might be considered the first Unitarian church in the country.

Freeman found support for his ideas from the English Unitarian, William Hazlitt, who visited Boston in 1784. Hazlitt promoted Freeman’s ministry and told him that he thought lay ordination scriptural. While the liberal Congregationalists tried to distance themselves from Hazlitt, both personally and theologically, Freeman gave him his friendship and said, “I bless the day when that honest man first landed in this country.”

As the congregation at Stone Chapel wished to remain connected with the Episcopal Church, in 1786 they sent a request to Bishop Samuel Seabury to have Freeman ordained as their rector. Because of the controversy surrounding the changes that had been made to Stone Chapel’s liturgy, Seabury replied that he would require the recommendation of his presbyters. After interviewing Freeman and confirming that he did not subscribe to the Trinity, the presbyters denied his application for ordination. A more liberal-minded clergyman, Dr. Samuel Provoost, bishop-elect of New York, also declined his support. The wardens of the church then took it upon themselves to arrange a lay ordination. In 1787 Freeman was made “Rector, Minister, Priest, Pastor, and Ruling Elder” of Stone Chapel.

A group of Episcopal clergymen in the area published a statement protesting “against the aforesaid proceedings, to the end that all those or our communion, wherever disposed, may be cautioned against receiving said Reader or Preacher (Mr. James Freeman) as a Clergyman of our Church, or holding any communion with him as such, and may be induced to look upon his congregation in the light, in which it ought to be looked upon, by all true Episcopalians.” A flurry of letters ensued, many of which were published in the local newspapers. One man even suggested that the “heretics” ought to be burned at the stake, as in the old days. The wardens of Stone Chapel, as well as the majority of the congregation, supported their new pastor in every way they could. Freeman himself kept aloof from the dispute and the controversy gradually subsided.

Freeman promoted Unitarianism outside the Stone Chapel as well. He donated to libraries tracts that had been sent to him by Lindsey. In 1792 a Unitarian congregation was formed in Portland, in the district of Maine, by an Episcopalian minister and friend of Freeman, Thomas Oxnard, to whom Freeman had given books by Lindsey and Priestley. His preaching in Baltimore in 1816 led to the organization of the Unitarian church there, at which William Ellery Channing gave his famous 1819 sermon. He met every two weeks with about twenty liberal ministers in the Boston area, mostly Congregational, for discussions relating to religion, morals, and civic order. Freeman was appointed to a committee charged with considering the creation of a formal body. The work of this committee led, in 1825, to the founding the American Unitarian Association.

In 1809, at Freeman’s request, Samuel Cary was brought in as a colleague at the Chapel. Cary, however, died in 1815 at only 30 years of age. Freeman again served the congregation alone until 1824, when Francis W. P. Greenwood was brought in to assist him. Greenwood later succeeded him.

In 1811 the Chapel revised its liturgy once again, incorporating changes that Freeman had wanted to make in 1785, but for which he had then thought the congregation not ready. That same year Harvard gave him an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree.

One of the founders of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Freeman served as its recording secretary from 1798-1812. He was a member of the American Humane Society, the American Academy of the Arts and Sciences, and the Massachusetts Peace Society. He served on the Boston School Committee for many years beginning in 1792, and was a delegate at the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention, 1820-21.

Freeman, who preferred the country to the city and was devoted to horticulture, lived in Newton, Massachusetts part of the year, residing in Boston during the winter. When he married Martha Clarke in 1783, he accepted her nine-year-old child, Samuel, as his own. In 1811, when they moved to Boston, Samuel and his wife Rebecca left their third son, James Freeman Clarke, later another influential Unitarian minister, under the care of James and Martha. Although the arrangement was supposed to be temporary, the boy ended up staying with his grandparents for the rest of his childhood.

In 1826, because of poor health, Freeman was encouraged by his physician to retire. He then resided full-time in Newton, where he was often visited by parishioners and friends. He died a few years later, at the age of 76. He was buried at Newton Cemetery. His wife Martha, who died in 1841 at the age of 86, lies in the Freeman tomb next to her husband.

Sources

Material on Freeman can be found in the archives of the Dr. Williams’ Library in London; the Houghton Library at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts (including the records of King’s Chapel); and in the the Davis Collection at the Henry Ford Museum Library in Dearborn, Michigan (personal letters, 1786-1806). In addition to various individual sermons, monographs, and a book of extracts from English Unitarian authors, Freeman published Sermons on Particular Occasions (1812), without his name on it. It passed through several editions. One version, Eighteen Sermons and a Charge (1829) was a special gift for his congregation. He also co-wrote (with Samuel Cary) Funeral Sermons Preached at King’s Chapel, Boston (1820). Freeman was an occasional contributor to the General Repository and Review and the Christian Register. Unfortunately his famous sermons on the Trinity are lost.

Sources for Freeman’s life include: Conrad Wright, The Beginnings of Unitarianism in America (1955); Samuel A. Eliot, Heralds of a Liberal Faith, vol. 2 (1910); Carl Scovel and Charles Forman, Journey Toward Independence: King’s Chapel’s Transition to Unitarianism (1993); Thomas Belsham, American Unitarianism, or a Brief History of the Progress and Present State of Unitarian Churches in America (1815); F.W.P. Greenwood, A History of King’s Chapel in Boston (1833); “Biographical: Rev. James Freeman, D.D.,” Christian Register and Boston Observer (January 9, 1836); Francis Parkman, “Review of Greenwood Funeral Sermon,” Christian Examiner and General Review ( January 1836); James Freeman Clarke, “Character of James Freeman, D.D.,” Western Messenger (January 1836); “Unitarian Reform: Number 2: History,” Western Messenger (December 1838); Henry Wilder Foote, “James Freeman and King’s Chapel, 1782-1787,” Religious Magazine and Monthly Review (July 1873); and Margaret Barry Chinkes, James Freeman and Boston’s Religious Revolution (1991). There is an entry on Freeman by Alan Seaburg in American National Biography (1999).

Article by David Miano

Posted July 11, 2006