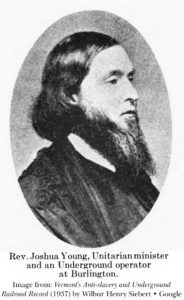

Reverend Joshua Young (September 23, 1823- February 7, 1904), Unitarian minister who served five congregations throughout his lifetime, was best known as the clergyman who officiated at the funeral of abolitionist John Brown. Along with his wife Mary (Plympton) Young, he was active in the Underground Railroad both in Boston, Massachusetts and in Burlington, Vermont. Ahead of his time,Young preached a radical understanding of equality among people of all races.

Joshua Young was born in 1823 to Aaron and Mary (Colburn) Young, in East Pittson, Maine, one of eleven children. The part of Maine where Joshua grew up was originally settled by the French. Compared to English or Yankee settlers, the French tended to have a more egalitarian relationship with the Penobscot and other indigenous peoples.

His family experienced non-congenital deafness. An older brother, at the age of nine, went deaf and was removed from regular school (though he went on to study at advanced levels and experience professional success). His father, as an adult, contracted severe hearing impairment which became Joshua’s fate as well.

Young attended Bowdoin College, graduating in 1845. He continued his professional training at the “University of Cambridge” (otherwise known as Harvard College). He trained for the Unitarian ministry, and graduated in 1848. He was ordained at New North Church in Boston, Massachusetts on February 1, 1849 with Frederic Henry Hedge preaching the sermon. Two weeks later he married Mary Elizabeth Plympton of Woburn, Massachusetts. The couple had four children; Joshua Edson, Henry, Gertrude, and Lucy. Bowdoin College would confer an honorary D.D. in 1890.

Joshua Young’s first call (1849) was to Boston’s New North Church, located on Hanover Street. Here the Youngs were introduced to the work of the Underground Railroad. Before, during, and after his pastorate at New North Church, he was a member of the anti-slavery Boston Vigilance Committee.

Young’s next call was to the First Congregational Church in Burlington, Vermont, in 1852. According to historian Elizabeth Curtiss, during his pastorate in Burlington, Young was “probably the most conservative Christian […] in Burlington. His family background was Congregationalist and Methodist on the New Hampshire/Massachusetts frontier line. However, Dr. Young’s strong and judgmental God had a major loving streak, for which reason, citing not Unitarian Cyrus Bartol but Baptist Rev. Hall, Dr. (then Rev.) Young introduced – in 1853 – fully open Communion […] coupled simultaneously with an offering for the poor. Thereafter he faithfully recorded the amounts given where his predecessors had recorded the numbers served bread and wine.”

On May 24, 1854, Anthony Burns, an escaped slave from Virginia who had been living in Boston, was captured for rendition. Like many Unitarian ministers, Young was in Boston for the annual “May Meetings” of Unitarians when Burns was imprisoned. It’s possible that Young witnessed the attempt by Abolitionists (including Unitarian ministers Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Theodore Parker) to free Burns from jail. When that failed Burns was returned into bondage and taken back South.

When Young returned to his church in Burlington he put aside his planned sermon. Inspired by the events he had witnessed in Boston he preached against slavery instead. He declared that the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act was “wicked and infamous – a dark deed of sin – an act of treachery” and that disobedience to this human-made law was obedience to God:

“but I have come back to fulfill a vow I then and there laid upon my soul, to plead the cause of the slave – the cause of human rights and liberty, with renewed zeal; to give whatever of talent God has bestowed on me, and whatever of influence I am permitted to exert, to the agitation and discussion of this evil, wrong, crime against man, sin against God – American Slavery.”

During his ministry in Burlington, Joshua and Mary Young continued their work with the Underground Railroad. Since the Canadian border was 50-60 miles away, Burlington was a key stop on the railroad. It is said that the Youngs hid fleeing African Americans en route to Canada in a “comfortable” barn. One account says the Youngs sheltered from one to six escaping slaves at any one time for over a decade. A second account says that Joshua was very active but seldom housed escaped slaves. The history is imprecise because Underground Railroad work was clandestine and few records were kept. In addition, stories recounted in later years were open to error and embellishment. It is thought that the Youngs collaborated with at least one person (Lucius Bigelow) from the Burlington Unitarian congregation along with other local Abolitionists including some associated with the University of Vermont.

In an 1854 abolitionist sermon, “God Greater than Man,” Young himself warned, “It may cost you your reputation, your friends, your property; it may cost you your life…”. A few years later members of the Burlington congregation were upset when Young was listed as a vice president for a June 1858 “Free Convention” in Rutland, Vermont. The New York Times called the convention a “curious gathering” of “Free-lovers, spiritualists, trance-mediums, abolitionists, and all sorts of queer people.” Young quickly renounced the convention for using his name. That November he offered to resign his position but the congregation met and “in an almost unanimous request” asked him to withdraw the resignation.

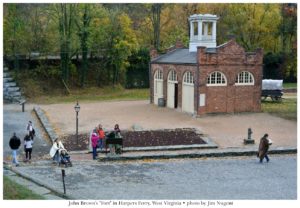

Like much of the nation, Young’s attention was drawn to the violent drama that took place at Harpers Ferry, Virginia in the middle of October 1859, when John Brown and his band of raiders attempted to foment a slave revolt to bring an end to “the peculiar institution” of American slavery. Most of Brown’s co-conspirators, including his sons, were killed in the unsuccessful attack. Those captured alive, including Brown, were brought to trial.

Public opinion was sharply divided about the raid and the trial. John Brown had staunch Unitarian admirers including some who provided financial backing, the most famous of which are referred to as “the Secret Six.” He also had detractors, including Unitarians, some of whom were members of Young’s own congregation. On Thanksgiving Day, 1859, Young invoked the lesson of Jesus who breaks the law of Sabbath in order to heal a human and set that person free from suffering (Matthew 12:12). He asked his congregation if they might rebuke him for raising the topic of “the aged prisoner in his lonely cell whose words of justification, from whatever standpoint we may judge his deeds, read to my heart like a new Evangel.”

John Brown was executed a few days after Young delivered that Thanksgiving Day sermon. Brown’s body was transported by train from Charlestown, Virginia to North Elba, New York, passing just south of Burlington. Young and Abolitionist friend, Lucius Bigelow, set off from Burlington to attend the funeral. Thwarted first by a storm-roiled Lake Champlain and second by a recalcitrant ferryman, they arrived four hours before the burial was scheduled to take place.

Upon Young’s arrival, Wendell Phillips, one of the more widely known Abolitionists, enlisted the clergyman to officiate at the funeral. Reports in the historical record suggest that Young was the only clergy present; other reports, not in contradiction, suggest other ministers had been asked to fulfill the task and had declined. The New York Daily Tribune recorded Young’s spontaneous prayer:

Almighty and most merciful God! we lift our souls unto thee, and bow our hearts to the unutterable emotions of his impressive hour. O God, Thou alone art our sufficient help. Open Thou our lips and our mouth shall show forth thy praise. Thou art speaking unto us; in those grand and majestic scenes of nature, so in the great and solemn circumstances which have brought us together. Our souls are filled with awe and are subdued to silence, as we think of the great, reverential, heroic soul, whose mortal remains we are now to commit to the earth, “dust to dust,” while his spirit dwells with God who gave it, and his memory is enshrined in every pure and holy heart. At his open grave, as standing by the altar of Christ, the divinest friend and Savior of Man, may we consecrate ourselves anew to the work of Truth, Righteousness and Love, forevermore to sympathize with the outcast and the oppressed, with the humble and the least of our suffering fellow-men.

We pray for these afflicted ones, this sadly bereaved and afflicted family. O! God, cause the oppressed to go free; break any yoke and prostrate the pride and prejudice that dare to lift themselves up; and O! hasten on the day when no more wrong or injustice shall be done in the earth; when all men shall love one another with pure hearts, fervently, and love with all their strength; which we ask in the name and as the disciples of Jesus Christ. Amen.

Young later wrote of his pastoral care of Mary Brown, John Brown’s widow, at the graveside: “as she stood there sobbing and overcome with her grief, I whispered to her for her consolation the sublime text from St. Paul:”

I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith. Henceforth there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness which the righteous judge shall give me at that day, and not to me only, but unto all them also that love his appearing. (2 Timothy 4:7-8)

The day after the burial, the newspaper in Burlington “attacked” him for uttering that particular scriptural passage in that particular circumstance. When he returned to Burlington, Young was met with strong, negative reaction to his participation at the Brown funeral. Given that the congregation was already “torn over the issue of slavery,” and some within the congregation suspected the Youngs of hiding slaves, numerous prominent families in his congregation took umbrage. Six left immediately. Others left at a slower pace.

Conducting John Brown’s funeral did not cost Young his life, but it did seem to cost him his pastorate and his social standing in Burlington, Vermont. According to Young himself:

I suffered the fate of all pronounced abolition preachers, returning from the grave of John Brown a social outcast, not fit to live, certainly not fit to occupy the pulpit, but must be driven out as I was. Cast out into the world with a certain stigma upon me for my sympathy with a ‘felon’ for whose family in distress I had dared to pray and had no apology to make.

At a congregational meeting on April 22, 1862 the congregation voted eight “contented” and 21 “not contented” with Young’s pastorate. The results of this vote were provided to Reverend Young “that he might take such action as he deemed proper.” Two days later, Young’s proper response was a letter of resignation with an effective date to coincide with the end of the fiscal year (end of March 1863), nearly a whole year later. In his resignation he wrote:

(New England Magazine, 1904)

I rejoice that no graver charge is made against me than that I have pushed the principles of general justice and benevolence too far; further than cautious policy would warrant and further than the feelings of some would go along with me. In every accident which may happen through life, in pain and sorrow, in depression, in distress, I will call to mind this accusation and be comforted.

While Young understood, and depicted for the public, that the no-confidence vote on his ministry was related to his abolition work and role in the Brown funeral, there are indications from other sources (including the editor of the Burlington Free Press at the time of Young’s retirement from ministry) that the basis for discontent may have included these, but was wider still. Despite this painful parting, some years later Young was invited back to that same church in Burlington to preach.

According to his own account, upon leaving the Burlington church, he went to Hingham to serve the Third Congregational Church (there were three Unitarian congregations in Hingham at the time). He then served the Unitarian Church in Fall River, 1868-1875. Eventually he arrived at First Parish Church of Groton, Massachusetts in December 1875. This was his last pastorate, and his longest, one he would serve 27 years.

Throughout his years in the ministry, Young was a Free Mason. Masonry brought together men with varied political and theological points of view

to pursue civic endeavors. Young served as chaplain of Old Colony Lodge in Hingham and for eight years he was chaplain of the grand lodge of Massachusetts. In 1894, while still the minister in Groton, Young was a founding member of the ecumenical Ministers’ Union, which consisted of “country ministers” of a variety of Christian faiths with the goal of promoting “the oneness of all believers.”

In 1899, the bodies of the original raiders at Harpers Ferry were transported north and buried next to Brown in North Elba, New York. Reverend Young, then 24 years into his lengthy pastorate at the Groton congregation, “took charge of the religious ceremonies.”

In 1902, Young and his wife retired to live with their son Henry in Winchester, Massachusetts. Joshua Young died in 1904 at the age of 81 and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His wife died in 1912 and was buried beside him. At some point his surviving family dedicated a plaque “in grateful remembrance of his devoted and happy pastorate.” It is located on the wall near the high pulpit in the Groton church’s sanctuary.

Sources

The Andover-Harvard Theological Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts has a minister file for Young and a handful of his letters to other clergy. A copy of his 1852 installation service in Burlington, Vermont can be found at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts while a letter to Young from Amos Bronson Alcott is in the Davis Family Library at Middleburg College in Middleburg, Vermont. Two sermons by Young; “God Greater than Man” (1854) and “Man Better Than a Sheep” (1859) are available as books. A magazine article by Young provides an overview of the 1859 John Brown funeral along with pictures of the 1899 reburial of John Brown’s accomplices. It was posthumously-published as “The Funeral of John Brown,” New England Magazine (April, 1904). His funeral prayer and benediction for Brown are found in the New York Daily Tribune (Dec 12, 1859). More about his resignation as minister in Burlington is found in William Siebert, Vermont’s anti-slavery and underground railroad record (1937). Additional information can be found in the Wilbur H. Siebert Papers at the Ohio History Center (online at ohiomemory.org).

This biography would not exist were it not for the primary source research in newspapers, denominational records, and congregational meeting minutes. This was done by Melinda Green of the Groton, Massachusetts church and Elizabeth Curtiss of the Burlington, Vermont church. A useful compilation of these items is found in a presentation by Elizabeth Curtiss, “The Passionate Heart of Joshua Young,” given at the First Parish Church of Groton, Massachusetts (2012). The New York Times has articles on the Rutland Convention and Young’s honorary Bowdoin degree while an obituary can be found in the Boston Globe (February 7, 1904). Many 1859 U.S. newspapers carried the story of Rev. Young’s service at John Brown’s funeral. A short biographical footnote on Young written by the Rev. H. G. Spaulding is available in “John Eliot and the Ministers of New North Church” in Samuel Atkins Eliot, ed., Heralds of a Liberal Faith: Volume 1 (1910). Also see the short biography, “Rev. Joshua Young, D. D.” in the Chi Psi Fraternity publication, Purple and Gold (1904).

For more on John Brown and his raid see, Edward Renehan, Jr., The Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown, (1997). For more on the Underground Railroad see Mary Ellen Snodgrass, The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations (2015); Michelle Sherburne, Abolition and the Underground Railroad in Vermont ( 2013); and Tom Calaro,“The Underground Railroad in Vermont: Tall Tale or True Adventure.” Also of interest is the song based on a Young sermon, “A Crown of Righteousness” by folk singer Pete Sutherland (1997).

Article by Melinda Green & Karen G. Johnston

Posted August 8, 2018