George Mortimer Pullman (March 3, 1831-October 19, 1897), best known for the palatial railroad sleeping and dining cars that bore his name, was a lifelong Universalist, a leading industrialist and one of the consummate industrial managers of the 19th century. Once hailed for building a model industrial town, Pullman, Illinois, he was reviled for his anti-labor stance after the town became the focal point of a nationwide railroad strike.

George was born in what is now Brocton, near Buffalo, New York, the third of ten children of (James) Lewis and Emily Caroline (Minton) Pullman. Lewis, a carpenter who developed a business moving buildings, had been raised a Baptist and Emily a Presbyterian. For several years after their marriage, they belonged to no church and conducted Sunday School classes for their children at home. Then, drawn to the “God is love” message of the Universalist evangelist minister Timothy C. Eaton, they began attending services and Sunday School at the Universalist church in nearby Portland, New York. Lewis often led services when no preacher was available.

George did not attend school after the fourth grade. He worked at his uncle John Minton’s general store in Westfield, New York, 1845-48. In 1845 his parents moved to Albion, on the Erie canal, east of Buffalo. At age 17 George joined his parents in Albion to work with his two older brothers and his father as a cabinet maker. The three sons also helped their father as he moved buildings along the Erie Canal. When occasional Universalist services were held in the local courthouse, the family attended.

Two of George’s brothers, (Royal) Henry Pullman (1826-1900) and James Minton Pullman (1836-1903), became prominent Universalist ministers. A graduate of Lombard University, Henry Pullman was ordained in 1855 and served churches in Albion, New York, 1854-55; Olcott, New York, 1856-59; Fulton, New York, 1860-66; Peoria, Illinois, 1867-71, and Baltimore, Maryland, 1877-1897. He served as General Secretary of the Universalist General Convention, 1872-77. In 1894 Lombard College awarded him an honorary D.D. James Pullman graduated from Canton Theological School, 1861, and was ordained in 1862. He was settled at Troy, New York, 1861-68; New York, New York, 1868-85; and Lynn, Massachusetts, 1885-1903. He served in the 1870s as Permanent Secretary of the General Convention. St. Lawrence University awarded him a D.D. in 1879. A distinguished preacher, he belonged to organizations working for the imprisoned and mentally ill and published a set of Sunday School Lessons, Studies in the Life and Teachings of Jesus, 1894-95.

Lewis Pullman died in 1853. George assumed responsibility for his father’s family and businesses. During the depression of 1857-59 Pullman traveled to Chicago. There he found opportunities to move buildings. In 1859-60 he and a Chicago partner elevated a number of Chicago buildings, and even whole blocks, to new street levels. In letters to his mother he assured her that he was going to St. Paul’s Universalist Church, often attending two services.

Meanwhile, the discomfort of riding on the newly built railroads and his knowledge of sleeping accommodations on canal boats had led Pullman to take an interest in sleeping cars. Before he left for Chicago in 1859, he had formed a partnership with a former New York state senator, Benjamin C. Field, who owned the rights to sleeping car construction in western states. In the summer of that year he converted two coaches on the Alton and St. Louis Railroad to sleeping cars.

In 1860, lured by gold, Pullman moved to the Colorado Territory. There he invested in and operated a dozen businesses involving mining, ore-crushing, saw milling, haying, building rental, and retailing. In three years he amassed a fortune estimated at $20,000 to $100,000. In 1863 he returned to Illinois. In 1864 he avoided service in the Union army by hiring a substitute to soldier in his place.

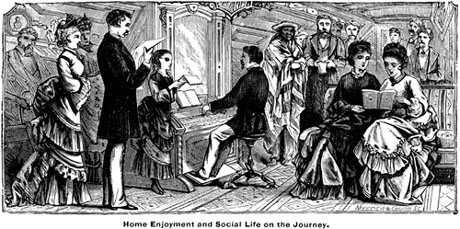

Pullman next invested in more lavish sleeping cars. He understood the rewards of advertising. He promoted his new cars with catered railroad excursions to the countryside for the press, railroad magnates, and politicians. (Many years after the opulent Pioneer was completed in 1865, company publicists started claiming that it had run in President Lincoln’s funeral train.*) Luxurious Pullman sleepers were very profitable. They featured trained and helpful staff, freshly washed linens, first-rate food and spotless accommodations. Early in 1867 he incorporated the Pullman Palace Car Company. In the same year he joined forces with Andrew Carnegie, who controlled key patents, to secure the transcontinental sleeping car business. Carnegie found Pullman “one of the most able men of affairs I have ever known.”

In 1869 Pullman bought out the Detroit Car and Manufacturing Company. In 1870 he bought the patents and business of his eastern competitor, the Central Transportation Company. In the spring of 1871 George Pullman, Andrew Carnegie, and others bailed out the financially troubled Union Pacific, and thus got themselves onto its board of directors. By 1875 the Pullman firm owned $100,000 worth of patents, had 700 cars in operation, and had several hundred thousand dollars in the bank.

In 1867 Pullman married Harriett (“Hattie”) Amelia Sanger, built a house in Chicago, and brought more of his family west. George and Amelia had four children: Florence born in 1868, Harriet in 1869, and twin sons George Jr. and Walter Sanger in 1875. Florence, her father’s favorite, was his frequent traveling companion. The Pullman family was socially prominent. George was fond of spending time with the Armours, the Fields and other wealthy Chicagoans at exclusive clubs and lavish social events. The Pullmans summered in the resort town of Long Branch, New Jersey, where President Grant also had a summer home. Good friends of the Grants, the Pullmans often stayed at the White House when in Washington, D.C.

In 1870, mixing business with pleasure, George took Hattie on a grand tour of Europe and scouted German, French, and British railroads. The Pullmans were active on the relief committee after the Great Chicago Fire, 1871. In 1877 Pullman completed a half-million-dollar Chicago mansion and in 1888 built a family retreat, Castle Rest, on Pullman Island in Alexandria Bay at Thousand Islands, New York. George’s brothers, Henry and James, often conducted open air Sunday services at Castle Rest for the family.

With his wife, Pullman attended services at Second Presbyterian Church, and also at First Universalist and the non-denominational Central Church. Having no appreciation of the theological or ritualistic aspects of religion, he did not comprehend the differences between faiths. Based upon his childhood training and life experience, he considered participation in public worship a duty, but applied religious teaching solely to interpersonal ethics, not to social issues.

Pullman’s philanthropy was related to his business enterprises. He wished young men to have opportunities for schooling and training at such institutions as the Chicago Athenaeum and the Chicago Manual Training School. His support for these schools provided businessmen, himself included, with a better quality of laborers. As an industrial capitalist he said he aimed to improve the “taste, health, cheapness of living and comfort among the artisan class.” Pullman charities, later administered by his daughter Florence, gave money to support an interracial hospital and to help Chicago blacks, as well as whites, get jobs.

Shortly after the Civil War, Pullman had begun hiring African Americans as porters and waiters. Although he paid them a fraction of what he paid whites, segregated them in menial jobs, and worked them harder than other workers, Pullman offered blacks better jobs and working conditions than did anyone else at the time. As porters, Southern black men escaped sharecropping and traveled around the country, where they learned new skills and found more opportunities. Their pay and tips held many black families together when other work was prohibited to them. Later, in the 20th century, Pullman employees became leaders in the civil rights movement.

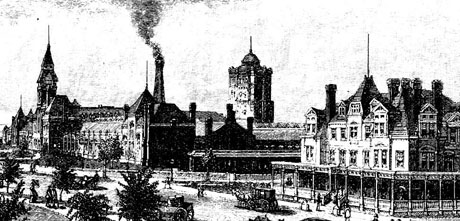

To shield his sleeper-car manufacturing workers from exposure to the alcohol, vice, disease, and labor unrest of Chicago’s crowded slums, Pullman decided to develop a model town where he could also centralize production. In 1880 he bought 4,000 acres of swamp land on Lake Calumet, 18 miles south of Chicago’s city center. He spent five million dollars to build a railroad car works, iron works, wheel works, power plant, and housing for 10,000 workers. Every home had indoor plumbing and gas lighting. There were paved streets, parks, an ice house, kilns for converting dredged lake clay into bricks, a sewage system, and communal stables. Workers easily walked from their homes to work in the adjacent factories.

Pullman, who named his town after himself, claimed he wasn’t motivated by charity so much as by capitalist practicality. Employees, living in a beautiful neighborhood, would work harder and better. Residences rented to them would pay for themselves and return 6% per annum. The workers, having paid for these pleasant surroundings, would appreciate them more than if he simply provided them. He thus offered his employees, not a gift, but opportunity to buy into an aesthetic and utopian dream. “I have faith,” Pullman told the press, “in the educational and refining influences of beauty, and beautiful and harmonious surroundings.”

Pullman owned the town. Every worker, business, and organization paid rent. Named for his oldest daughter, the Hotel Florence had the only bar in town, open to visitors only, not the residents. He donated 4,000 books to initiate the Pullman library. He planned that all religious denominations should band together and share a single building, the Greenstone Church, the only church building permitted in town. As he did not see any essential differences between the several churches in his own life, he did not understand the importance of distinct faith communities in the lives of others. His impractical church dream came to nought, since those of different denominations would not unite and no one denomination could afford the rent. The building remained unused until 1885 when he reduced the rent by two-thirds.

Thousands of American reporters, authors, reformers and capitalists visited Pullman, Illinois. During the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair 10,000 foreigners visited the town. Economist Richard T. Ely, writing for Harper’s, praised the town’s beauty and efficiency, but described its design as one of “benevolent, well-wishing feudalism, which desires the happiness of the people, but in such a way as shall please the authorities.”

With no sense of ownership or any stake in the community, most residents stayed only briefly. One person told Ely, “We call it camping out.” Other towns—in which workers could own land and build houses and which had a variety of churches, bars, and businesses—soon sprang up around Pullman.

But even though many of the Pullman workers were isolated in the town of Pullman, the company suffered periodic labor stoppages during the 1880s. Pullman would neither allow labor unions nor listen to complaints nor negotiate with employees. He did, however, usually allow holdout workers to return to their jobs after failed strikes. Then in 1893 the stock market crashed. The subsequent depression closed 150 railroads and brought massive unemployment. To maintain corporate dividends, Pullman cut factory workers’ wages by 25 percent or more, but did not reduce rents in the town of Pullman at all. He met with workers, but only to explain corporate policy. He refused to discuss their grievances.

In 1894 4,000 Pullman employees, members of the Eugene V. Deb’s American Railway Union, went on strike. That July 100,000 railroad workers across the country refused to handle Pullman railroad cars. Pullman’s friend and fellow railroad director, United States Attorney General Richard Olney, with President Cleveland’s backing, sent troops to Chicago to ensure that U.S. mail would not be delayed. The arrival of troops sparked riots in which six people died. The mayor of Chicago asked the Pullman Company to submit to arbitration. Pullman refused, saying, “Arbitration always implies acquiescence in the decision of the arbitrator, whether favorable or adverse.”

The strike, and Debs’s union, was broken when the troops moved the trains. The Pullman company only rehired workers who promised never to join a union. Many former employees faced starvation. Pullman refused to donate any aid even when the Governor of Illinois appealed to him to do so. His attitude throughout was, at best, one of tough fairness with little charity. Although he honored Universalism as the religion of his parents and his upbringing, he did not seem to understand the implications of its central message, “God is love.”

In public, Pullman and his family paid little heed to the strike. Pullman occupied himself with building a Universalist church—Pullman Memorial—in the hometown of his youth, Albion, New York, dedicated in 1895. At the laying of the cornerstone Henry Pullman said, “The desire of my brother in the erection of this church is to establish a memorial of the father and mother who believed in the doctrines of the Universalist Church and who lived their lives among the people of this community.”

In the months after the strike, a federal commission was convened to investigate its causes. The commission censured Pullman for charging excessive rent, for attempting to saddle his employees with all his company’s depression losses, and for denying the workers any protection or voice. In 1898, as the result of a lawsuit filed in the wake of the investigation, the Illinois Supreme Court ordered the Pullman Palace Car Company to sell its non-manufacturing real estate. The town of Pullman, though absorbed into Chicago, did not change much in appearance during the next century.

Under the stress of circumstances Pullman’s heath declined. In 1897 he died of a heart attack. His will included a bequest of $1.25 million for a manual trades school to be built in Pullman, Illinois.

Pullman’s pride and insistence on full control made him successful in business, but damaged his reputation. His name was linked with industrial tyranny. American Federation of Labor founder Samuel Gompers called him an “avaricious wealth absorber, tyrant, and hypocrite.” Historian L. E. Leyendecker said that, “Once fallen from grace, Pullman was among the first industrialists to be attacked by reformers. He was particularly vulnerable because his personal lifestyle and the town he created had been highly publicized.” Other industrialists and financiers, better attuned to public opinion, moved quickly to become more public-spirited.

Sources

* Seven all new sleeping cars manufactured and owned by George M. Pullman travelled with the the Lincoln funeral train from Chicago to Springfield, Illinois according to a report by a special correspondent of the New-York Daily News (Monday, May 8, 1865).

Three thoughtful and thorough biographies, each written in a different era, are Almont Lindsey, The Pullman Strike: The Story of a Unique Experiment and of a Great Labor Upheaval (1942); Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning, 1880-1930 (1967); and Liston Edgington Leyendecker, Palace Car Prince: A Biography of George Mortimer Pullman (1992). Donald L. Miller, City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America (1996) and Carl Smith, Urban Disorder & the Shape of Belief (1995) cover Pullman within broader contexts, while Richard O. Boyer & Herbert M. Morais, Labor’s Untold Story (1955) provides labor perspective. John H. White, The American Railroad Passenger Car (1978) and Charles M. Knoll, Go Pullman (1995) cover Pullman in the flow of railroad and industrial history. Written closer to events, and with more evident bias, are William H. Carwardine, The Pullman Strike (1894); Mrs. Duane Doty, The Town of Pullman Illustrated: Its Growth with Brief Accounts of Its Industries (1893); and Richard T. Ely, “Pullman: A Social Study,” Harper’s Magazine (February 1885).

Article by Jim Nugent

Posted May 12, 2004