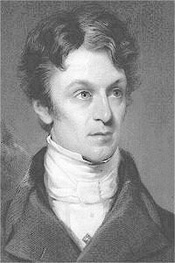

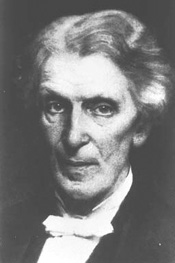

James Martineau (April 21, 1805-January 11, 1900) was a Unitarian minister and educator, and a widely influential theologian and philosopher. As lecturer and Principal at Manchester New College, he was for many years responsible for training ministerial students. As a leading intellectual of 19th century England, he was an admired friend of poets and philosophers who testified to their debt to thought and work. He wrestled with questions concerning the Bible, sources of authority, the meaning of Christ, the validity of non-Christian religions and the roles of reason and conscience. He helped to shape both Unitarian and general religious thought.

His ancestor Gaston Martineau, a Huguenot refugee, had settled in Norwich after the revocation of the Edit of Nantes in 1685. Born in Norwich, James was the seventh of eight children of Thomas and Elizabeth (Rankin) Martineau. His father was a manufacturer of camlet and bombazine. The family worked for many years after 1823, when a financial crisis destroyed his business, to pay off his debts. They never sought the protection of bankruptcy. Martineau later explained, “Whoever avails himself of mere legal release as a moral exemption, is a candidate for infamy in the eyes of all uncorrupted men.”

A friend spoke of James as “an irritable child.” As a youth he was thin, timid and nervous. James said his childhood was not happy, due to the “well-meant yet persecuting sport” of his older brothers and rough treatment at Norwich Grammar School. His closest companion was his slightly older sister Harriet, later a celebrated writer.

The Martineaus were members of the Octagon Chapel in Norwich, an English Presbyterian church. (They were Rational Dissenters, but could not legally call themselves Unitarians before 1813). According to family tradition, one Sunday James was found seated on a little stool before a great Bible resting on a chair. He claimed to have read from the beginning through Isaiah since morning chapel. When his mother chided him for exaggeration, he said he had done it by “skipping the nonsense.”

Having attended the boarding school of Lant Carpenter in Bristol, 1819-21, James was apprenticed to Samuel Fox of Derby to become a civil engineer. The death in 1821 of a beloved minister, Henry Turner (son of William Turner), “worked his conversion,” as he later wrote, “and sent him into the ministry.” Thomas Martineau, disappointed, warned his son that he was courting poverty but supported his decision.

In 1822 Martineau entered Manchester College, York. Charles Wellbeloved, John Kenrick, and William Turner were his instructors. Principal Wellbeloved was an especially strong influence. As a student Martineau worked hard and won high honors. In 1825 he delivered his oration, “The Necessity of Cultivating the Imagination as a Regulator of the Devotional Feelings.”

Having left York in 1827, Martineau was for a year head instructor at Carpenter’s school in Bristol. Then he was called as co-pastor at Eustace Street Chapel in Dublin, Ireland where he was ordained by the Dublin Presbytery, Synod of Munster, with laying on of hands. Two months later he married Helen Higginson, daughter of the Unitarian minister, Edward Higginson, in whose Derby household he had earlier boarded. The Martineaus had eight children, two of whom died young. Their son Russell Martineau (1831-1898) was lecturer and then Professor of Hebrew at Manchester College, 1857-74.

When Martineau succeeded as full pastor in 1831, he was entitled to the regium donum, a benefit of the crown awarded to Irish dissenting ministers. He refused it on the grounds that it was state support of the churches, and that tax money paid by Roman Catholics unfairly supported Protestant churches. His refusal brought on his resignation. A few months later he began a long ministry at Paradise Street Chapel (later Hope Street Church) in Liverpool, 1832-57.

Martineau’s first book, Rationale of Religious Enquiry, 1836, placed the authority of reason above that of Scripture. The book marked him among older British Unitarians as a dangerous radical, much as the Divinity School Address of 1838 did Ralph Waldo Emerson in New England. In 1839 Martineau and two colleagues, John Hamilton Thom and Henry Giles, engaged in “the Liverpool Controversy,” an extended public disputation with Anglican clergy over Trinitarian and Unitarian interpretations of scripture. Martineau’s scholarly and eloquent arguments attracted popular attention and much enhanced his reputation. William Ellery Channing wrote to Harriet Martineau that her brother’s Liverpool Controversy lectures “seem to me among the noblest efforts of our times. They have quickened and instructed me. Indeed, his lectures and Mr. Thom’s give me new hope for the cause of truth in England.”

In 1840 Martineau was made Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy and Political Economy at Manchester New College, then moved back to Manchester. When the college moved to London, he commuted from Liverpool, 1853-57, to lecture. In 1857 he resigned his Liverpool pulpit and moved to London to devote himself entirely to his educational duties.

In 1848-49, a year of vacation and study in Germany, Martineau was exposed to German idealism. Impressed by David Friedrich Strauss’s Life of Jesus, 1835, and calling this a time of “new intellectual birth,” he gave up his previous belief in determinism and became a Transcendentalist. He acknowledged his debt to American Unitarians Channing, Emerson and Theodore Parker.

Martineau wrote for the London Review, 1835-51, and the Theological Review. He edited the Prospective Review, 1845-54, and its successor, National Review, 1855-64. In 1851 he published “Mesmeric Atheism” in Prospective Review. In it he reviewed satirically the philosophy of positivism spelled out in Henry George Atkinson’s Letters on the Law of Man’s Nature and Development, edited by Harriet Martineau. The article led to a permanent break with his sister.

In 1866 the Chair of the Philosophy of Mind and Logic at University College, London, became vacant. Martineau applied for it. Although considered highly qualified, he was rejected on the ground that as a clergyman he would be biased. Prof. Augustus de Morgan, a mathematician, resigned his own chair at the University in protest. The Council of the College was severely criticized by many on the faculty and others who saw the move as a betrayal of trust.

Succeeding Edward Tagart as pastor at Little Portland Street Chapel in London, 1859-72, Martineau preached to a distinguished congregation including Charles Dickens, Charles Lyell and Frances Power Cobbe. J. Estlin Carpenter wrote that when Martineau retired from the Chapel “many felt that something of the music of existence ceased for them when his voice was no more heard.” Cobbe said she walked beside him and expressed her sorrow that she would no longer hear his preaching. She wrote, “His head drooped; and he replied with infinite sadness in a low voice: ‘It has been my life.'”

In the 1830s and ’40s British Unitarians faced a crisis. Orthodox dissenters made legal claims to their trusts and property. Martineau helped to invent “the open trust myth,” according to which “English Presbyterians” had put their meeting houses and funds in trust for the worship of Almighty God alone, without requirements of creed and confessions of faith. The myth conveniently ignored the requirement of subscription to the Church of England’s 39 articles of faith, except in matters of worship, and in the 1689 Toleration Act, which specifically excluded anti-trinitarians. The liberals claimed that, otherwise orthodox as may have been their Presbyterian ancestors, they were enlightened enough not to inhibit their descendants doctrinal development. After initial legal disasters and loss of funds, the myth began to be believed. By the Dissenters Chapels Act of 1844, British Unitarians were secured in their trusts and property.

Martineau did little to promote his influence in church circles. He turned down high positions, including presidency of the British and Foreign Unitarian Association. Yet he maintained a busy schedule of preaching at Unitarian churches and often participated in ministers’ inductions (called installations in America).

Although he strongly professed his Unitarian faith on many occasions and upheld Unitarian teachings—the humanity of Jesus, the unity of God, the role of critical method in Biblical interpretation—Martineau thought it an error to name a religion after a doctrine, even a doctrine of God. He said the name Unitarian indicated merely another dogma,”a different doxy” from orthodoxy. He urged churches not to use the name “Unitarian,” and suggested “Free Christian Church” as a broader term. A number of British Unitarian churches adopted the name. As a result British Unitarians to this day gather themselves as the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches.

Siding with those who wished to emphasize their catholicity, not specifically Unitarian doctrine, Martineau in 1868 helped to form the Free Christian Union which he hoped would unite in worship mutually tolerant people: Dissenters, Anglicans and others of varied personal beliefs. He did not possess, however, the organizational skills to forward his dream. The Free Christian Union did not attract a substantial following and dissolved in 1870.

Stopford Brooke was a prominent Anglican and chaplain to Queen Victoria when he became Unitarian. Dean Stanley begged him to remain within the established Church, saying, “We need you, and men like you, to help us broaden the Church of England till it can hold all sincere Christians.” Brooke asked, “Do you think, Dean, that in your time or in mine it will be broad enough to make Martineau Archbishop of Canterbury?” Stanley said, “I am afraid not.” Brooke answered, “Then it will not be broad enough for me.”

Martineau believed in the importance of the church. Its primary role is worship; otherwise, it becomes a club, or something like any other special purpose organization. The fellowship of the church is a community in historical continuity with earlier generations going back to Christ. The church is a society for realizing harmony with the divine. Unitarians stressed free inquiry. Martineau insisted the church must be more than an association for free inquiry. A common bond, a consensus of purpose to worship, must unite worshipers, or individualism will promote mere anarchy. The church is “the Society of those who seek harmony with God.”

Martineau considered worship an end, not a means. He held that religion must be concerned primarily with individual regeneration. He opposed any utilitarian view that worship must have usefulness beyond opening the soul to divine inspiration. He did not preach doctrine, Unitarian or otherwise. His eloquent pastoral sermons aimed to bring people into closer relation with God, to lift up the path to righteous living and a developed spiritual life. They often dealt with personal problems such as grief and loneliness. In sermons he never discussed economics, politics or social reform, though he did so frequently in lectures and articles. He thought social justice, which he advocated strongly, should follow from theology, not replace it. Because his sermons did not discuss current issues, they retain their freshness today.

Martineau spent much of his life training ministers. He taught that the minister’s task, the highest form of service to humanity, is to declare the truth and to remind people of their divine promise. He considered the minister’s primary function to be leading public worship. The minister may fill many other roles—teaching, education or social action—but those should not be part of worship. He was critical of pressure put on ministers to measure success by the number on the roll or in attendance. He said those criteria make ministers too prone to trade the stern demands of the gospel for popular topics. He taught that when ministers are expected to give many public addresses, encourage public causes or act like socialites, the ministry is ill-defined and thus weakened.

A preacher’s preacher, Martineau was much appreciated by many broad church Anglicans who read his sermons. But his enormous public reputation did not translate into large congregations. His sermons were often easier to read than to hear. Today’s readers may enjoy his sermon collections, Endeavours after the Christian Life, 1843 and 1847; Hours of Thought on Sacred Things, 1876 and 1879; and National Duties and Other Sermons and Addresses, 1903.

In 1860 a group of London Unitarian ministers published Common Prayer for Christian Worship. Some of its material is of Martineau’s composition. In a revised edition he omitted all instances of “through Jesus Christ our Lord.” He widened the repertoire of psalms and hymns used in British Unitarian churches. He edited three hymn books, A Collection of Hymns for Christian Worship, 1831; Hymns for the Christian Church and Home, 1840; Hymns of Praise and Prayer, 1873, the latter two widely used in British Unitarian churches. In them he introduced hymn texts from “spiritual” and “pietist” traditions, including some by Samuel Longfellow, Samuel Johnson and other Harvard school hymnodists.

Martineau wrote extensively on authority in religion. Seeking harmony between reason and faith, he began conventionally, accepting the authority of the Bible. He turned to reason and in the end settled on conscience as the ultimate authority, according to Martineau, the voice of God within. Translating Kant’s idealist philosophy into theology, he argued that human nature is close to God’s nature and is part of the Absolute Mind. He believed that human nature, at its best, reflects God.

Martineau worshiped a personal God. He did not mean by the term that he thought God a person, but that each person has a personal relationship with God. The personal God is reflected in human nature. He wrote, “Shall I be deterred by the reproach of ‘anthropomorphism’? If I am to see a ruling Power in the world, is it folly to prefer a man-like to a brute-like power?” He could not believe in God as a force of nature or as unconcerned. He said, “God is an all-embracing Love, an inexhaustible holiness, an eternal pity, an immeasurable freedom of affection.”

Ethics, according to Martineau, is more than a social contact among like-minded people. Human obligations are not matters of opinion, or arbitrary. He held moral law to be an expression of God’s will, inherent in the structure of the universe. Like physical law, moral law is discovered, not invented. Intuition discovers moral law, by examining the lessons of history and by giving heed to inspired people. Religion without moral law would lack the requirement of duty. He held doing good not sufficient; there must be some vision of the good to be accomplished. As we strive for the right, undertake works of charity and, most importantly, develop our spiritual nature, we see God. On the other hand, “to one who dishonours himself by sloth and excess, God becomes invisible and incredible.”

Martineau admired Jesus, not as a “Messiah” or “Lord,” nor as Intellectually infallible, but as an inspired man filled with the spirit of God. Jesus revealed to us a devotion to God that can strengthen our conscience. When we know our own highest and best, we are in fellowship with God. Jesus’ Father becomes our Father. Thus, as Jesus was the incarnation of God, so are we all. Martineau prayed, “In all things, draw us to the mind of Christ, that thy lost image may be traced again, and thou mayest own us at one with him and thee.”

To Martineau, to be a Christian was to follow where Christ led. He wished to avoid theological speculation about Christ’s person and concentrate on his teachings. Nevertheless, to adopt the religion of Jesus was not to give preference to earliest Christianity. One form of Christianity was not better because it was older, he said. Martineau gladly used the methods of historical criticism to understand the Bible. He rejoiced in the light that science shed on theology. He investigated and spoke well of non-Christian religions. He wrote that he wanted “Christianity purified of superstitions, a Church intent only on Righteousness, and a Social habit of justice and charity to all men.”

Martineau was a member of the Metaphysical Society, 1869-80, founded by Lord Tennyson. He held a prestigious and influential position as trustee of Dr. (Daniel) Williams’s Trust, 1858-68, established in the 18th century to further the education of clergy. Martineau was given honorary degrees by five universities—Harvard, 1872; Leyden, 1875; Edinburgh, 1884; Oxford, 1888; and Dublin, 1892. On his 83rd birthday he received accolades from Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, Benjamin Jowett, Ernst Renan, William James, Joseph Chamberlain, James Russell Lowell, Charles Eliot, and many others. He replied with characteristic modesty, “To be held of any account by the elite of those to whom I have habitually looked up . . . is an honour simply mysterious to me.”

Martineau was a friend of Bishop John Colenso, Anglican bishop of Natal, whom he tried to have appointed to the Chair of Old Testament at Manchester College. Lord Tennyson was his lifelong friend. Others were José Blanco White; G.G. Bradley, Dean of Westminster; Francis William Newman, brother of Cardinal Newman; William Gladstone; Cardinal Henry Manning; Mrs. Humphrey Ward; John Stuart Mill; Prof. Thomas H. Huxley; Prof. Henry Sidgwick; and Prof. John Tyndall.

A man of discipline, Martineau never smoked and twice gave up drinking. Efficient in his work, he carried on voluminous correspondence. Politically, he was of the old Whig school and shared the concerns of the merchant and manufacturing class from which he had come. Gentle and dignified, he conversed with a courtly grace. A friend, Alexander Craufurd, an Anglican vicar, said, “Of all deep thinkers whom I have ever known he was the most free from the depressing modern malady of pessimism.”

Martineau taught at Manchester College until 1885 and was Principal, 1869-85. After he retired from the College at the age of 80, he wrote his best known works. He published Types of Ethical Theory, 1885; A Study of Religion, 1888; and Seat of Authority in Religion, 1890. These volumes constitute an impressive systematic Unitarian theology.

Death

Helen Martineau died in 1877. When Martineau died at the end of the century, he was buried next to his wife in Highgate Cemetery in London. He is commemorated by a portrait and a statue at Harris Manchester College of Oxford University.

Sources

James Martineau’s works and manuscripts are located mainly at Harris Manchester College, Oxford, England. The college has a large collection ofbooks from his library and books about him. There are letters from Martineau at John Rylands University Library of Manchester and at the Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, California. Among the works of Martineau not mentioned above are Studies of Christianity (1858), A Study of Spinoza (1882), Faith and Self-Surrender (1897). Many of his sermons were translated into German and Dutch. A good but brief resource is Alfred Hall, James Martineau Selections (1951).

There is no recent biography of Martineau. Among the older works are James Drummond and C. B. Upton, The Life and Letters of James Martineau, 2 vol. (1902); A.W. Jackson, James Martineau, A Biography and Study (1901); Alexander H. Craufurd, Recollections of James Martineau (1903); and J. Estlin Carpenter, James Martineau, Theologian and Teacher (1905). There are numerous articles on Martineau in Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society (TUHS) and in Faith and Freedom (FAF). Among these are Anthony J.Cross, “James Martineau with the Pope on the Lord’s side,” FAF (Autumn/Winter 1996) and “Moving Martineau off the miracles: the role of Joseph Blanco White,” FAF (Autumn/Winter 1995); Murray Bracey, “James Martineau: apostle of catholicity,” FAF (Spring/Summer 1993); Gayle Graham Yates, “Harriet Martineau and her brother James,” FAF (Summer 1986); and Ralph Waller, “James Martineau revisited,” FAF (Summer 1985); “The Liverpool Controversy,” FAF (Spring/Summer 1994); and “Scenes of Manchester College from the eyes of James Martineau,” TUHS (1997). Ralph Waller, “James Martineau: the development of his thought,” in Barbara Smith, ed., Truth, Liberty, Religion: Essays Celebrating Two Hundred Years of Manchester College (1986); and Ralph Waller, “James Martineau in Dublin” and “James Martineau and the catholic spirit amid the tensions of Dublin, 1828-1832,” in W. J. Sheils, and Diana Wood, The Churches, Ireland and the Irish (1989). A recent book on Martineau’s theology, with emphasis on his theory of worship, is James Martineau: “This Conscience-Intoxicated Unitarian”, by Frank Schulman (2002).

Article by Frank Schulman

Posted December 2, 2002