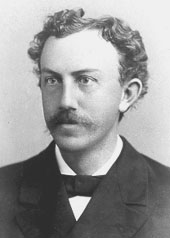

David Starr Jordan (January 19, 1851-September 19, 1931), an ichthyologist and an early teacher of evolutionary science, was president of Indiana University and Stanford University and a prominent peace activist. Brought up by Universalists, he associated with Unitarians and Universalists and their organizations, held liberal religious beliefs, and was treated as a philosophical spokesman by the American Unitarian Association, but did not join a Unitarian or Universalist church in adulthood and remained almost entirely aloof from organized religion.

Born near Gainesville, New York, David was the son of Huldah Lake Hawley and Hiram Jordan. He chose Starr for his middle name because of his love for astronomy and to honor his mother’s respect for the Unitarian and Universalist minister, Thomas Starr King. His parents had been Baptists when they first married, but soon left “because of their doubts as to ‘eternal damnation'” and joined the Universalists. Jordan later claimed, accordingly, to have been “brought up under strong religious influences untouched by conventional orthodoxy.”

In his youth David attended revivals, once even going forward “with others looking for ‘conversion,'” but the experience had no lasting effect: “I was sincere enough in this matter, but it made no real difference in my life so far as I remember, and was accompanied by no special ‘conviction of sin.'” Early in his life he “acquired a dislike for theological discussion, believing that it dealt mostly with unrealities negligible in the conduct of life.” He, therefore, “never had to pass through a painful transition while acquiring the broader outlook of science and literature.”

By fourteen, David had “outgrown” the district school. Since he was considered to be a “youth of promise and otherwise apparently harmless,” he (and another boy) were admitted to the Gainsvilles Female Seminary, a secondary school modeled after Mount Holyoke. In 1869 he entered the newly established Cornell University, graduating in 1872 with a Master of Science for his advanced work in botany.

Jordan began his academic career at Universalist Lombard College, 1872-73. He left under duress, as the University trustees did not appreciate his teaching the students about geological ages. This disappointment may have ended any attachment he had to the Universalists. He spent the following two summers, 1873 and 1874, studying and working at Louis Agassiz’s school on the island of Penikese in New York. He gradually grew to accept Charles Darwin’s theories, which his mentor Agassiz opposed. Jordan initially approached Darwinism with great reluctance: “I sometimes said that I went over to the evolutionists with the grace of a cat the boy ‘leads’ by its tail across the carpet!”

At Penikese Jordan met Susan Bowen, whom he married in 1875. They had three children, Edith, Harold, and Thora.

After a year as principal of Appleton Collegiate Institute in Wisconsin, 1873-74, Jordan taught high school science in Indianapolis, Indiana, 1874-75, and studied medicine at Indiana Medical College (M.D., 1875). While professor of natural history at Northwestern Christian University (later Butler University), in Indianapolis, Indiana, he earned his Ph.D. He taught at Indiana University, beginning in 1879, and was made Chairman of the Department of Natural Sciences. In 1885 Jordan was selected the seventh president of Indiana University. At age thirty-four, he was the youngest college president in the nation and one of only two scientists presiding over American universities. The other was Charles W. Eliot of Harvard.

Jordan, who kept up his research and teaching after becoming an administrator, was the most influential American ichthyologist in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He was also an inveterate traveler, often taking students with him. He and his students discovered more than 2500 species of fish, and named 1085 of them.

Among the courses he taught at Indiana University were several on evolution, including the “Study of Darwin’s Life and Letters.” Years later, he probably exaggerated the truth by claiming: “I taught evolution as a course at Indiana for the first time it was taught as such in the world.” He eventually published books and articles on evolution including Darwinism, a Brief Account of the Darwin Theory of the Origin of Species, 1888, Footnotes to Evolution, A Series of Popular Addresses on the Evolution of Life, 1898, and The Relation of Evolution to Religion, 1926, a tract published by the American Unitarian Association. In 1909, on the one-hundredth anniversary of the births of Abraham Lincoln and Charles Darwin—and the birthday of his own father—Jordan spoke about the influence of Darwin at the Unitarian Club of San Francisco.

Jordan’s first wife Susan died in 1885, and shortly after her death, he also lost his daughter, Thora. In 1887 he married Jessie Louise Knight with whom he had three more children, Eric, Knight, and Barbara.

Jordan was the first president of Leland Stanford Junior University (later Stanford University), 1891-1913. He was afterwards Chancellor, 1913-16, and Chancellor Emeritus, 1916-31. Despite serious financial difficulties caused by the death of founder Leland Stanford in 1893 and major damage to the campus by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, Stanford grew quickly under Jordan’s guidance. He introduced the elective system that he had developed at Indiana University. With the support of the founders, he kept the campus free of sectarian influences.

In 1900 university trustee Jane Stanford urged Jordan to dismiss Professor Edward A. Ross, whose outspoken political positions had angered her. “I had a double problem,” Jordan wrote in his autobiography, “to shield the University from uninformed or unsympathetic criticism . . . and to protect the reputation of a young professor from the natural consequence of his indiscreet adventures in thorny paths of partisan politics. I failed in both efforts.” Ross left Stanford and seven other faculty members resigned in protest. Jordan was attacked by the press and his reputation as an educational leader was marred for his having been associated with an infringement of academic freedom. He recalled this as a “painful and trying episode.”

Jordan was the first president of the Indiana Academy of Science, 1887; the president of the California Academy of Science, 1895; and a charter member of the Sierra Club, 1891. In 1909 he was elected president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and in 1921, named an honorary Associate in Zoology in the Smithsonian.

In 1900 Jordan chaired the committee that established the constitution for the Association of American Universities. He was the president, 1915, of the National Education Association, and in 1906 he became a member of the first board of trustees for the Carnegie Foundation for the Improvement of Teaching, a position he held for the next ten years.

Jordan believed that “the final end of education is not learning or official position, but service to humanity.” The greatest service he could envision was the promotion of peace and the elimination of war. He soon endured criticism for his outspoken position. In 1909, after he addressed the California Socialist Party, a scheduled lecture at the University of North Carolina was canceled. In 1917, a mob chided Jordan in the streets of Baltimore singing, “Hang Dave Jordan in a Sour Apple Tree.” The following year some Cornell alumni asked that his degree be rescinded for un-American activity.

Jordan served as chief director, 1909-11, of the World Peace foundation and dean of the American section of the World Peace Congress at The Hague, 1913. In 1925 he won the Herman Peace Prize for the best educational plan for preserving world peace. Among writings on peace are World Peace and the College Man, 1916; Ways to Lasting Peace, 1916; and The Outlawry of War, 1927.

Jordan shared his commitment to peace with Jenkin Lloyd Jones, whom he described as “one of my most valued friends.” Some of Jordan’s pacifist articles were published in Unity, a periodical founded by Jones. The two, however, disagreed on strategy after the outbreak of World War I. When Congress declared war, Jordan decided to cease speaking against the war because it was “neither wise nor reasonable to oppose in any way the established policy of the nation.” In a 1917 letter to Jordan, Jones wrote accusingly, “Et tu, Brute? Where are you? Unity will be glad to print a message from you.” If there was a rift in Jones’s relationship with Jordan, the break healed quickly. A few months later, Jones wrote to Jordan asking his permission to place his “name among the editorial contributors on Unity‘s doorplate” Jones added that Jordan’s “spiritual attitude and mental fertility have meant very much to me.”

Jordan’s pacifist convictions were in part based on the pseudo-science of eugenics. He believed that war destroyed the best of humanity, leaving the weaker members of society to produce the next generation. He, nevertheless, did not support the more radical implications of eugenics. “The artificial breeding of the superman” he said in The Heredity of Richard Roe, a Discussion of the Principles of Eugenics, 1911, “would defeat its own ends.” He explained, “It would breed out of existence the two most important factors the race has won . . . love and initiative. The superman produced by official eugenics would not take his fate into his own hands, and his descendants would not know the meaning of love.”

Along with nineteen other educators, Jordan was invited by the American Civil Liberties Union to serve on the Tennessee Evolution Case Fund advisory committee to raise money for the defense in the John Scopes trial. At the end of the 1925 trial, Jordan chaired a committee to raise scholarship funds for Scopes to attend graduate school at the University of Chicago.

Jordan was the number-one author for Beacon Press during the tenure of Charles Livingston Stebbins, 1902-13. During that period, Beacon published 19 of Jordan’s books, more than by any other single author. In addition to his many professional publications, Jordan wrote poetry, children’s books, and texts on religious themes, including The Story of the Innumerable Company, 1895, (reissued as The Wandering Host, 1904) and The Religion of a Sensible American, 1909. These latter books were published by the American Unitarian Association.

In 1875, while at Northwestern Christian University, Jordan joined Plymouth Congregational Church in Indianapolis. He later claimed that “it was the only religious organization I ever formally joined.” He was attracted to the congregation by its pastor, Oscar McCulloch, “a most humanly genial and broadminded man” whom Jordan admired because of his “fine work, religious, social, political, and charitable.” But Jordan did not remain a member of the congregation for long, and he was never baptized. At that time, moreover, he was disturbed by and resisted the religious pressures being applied to the faculty members by the Christian trustees.

Although not a member, Jordan did associate with Unitarians, was published by Unitarians, and spoke at their events. For example, in 1898 Jordan addressed an evening session of the Pacific Unitarian Conference at Oakland. His speech, entitled “The Religion That Will Endure,” was published in Pacific Unitarian (May 1898).

Throughout his life, Jordan remained uncomfortable with organized religion, claiming that the “machinery of worship is mistaken for its essence,” and that “much that we have called religion is merely the debris of our grandfather’s science.” “Intolerance is unscientific,” he wrote in 1883. “So is it unchristian.” For him, true religion was “individual, not collective,” and “concerned with life, not with creeds or ceremonies.” In Ulrich Hutten, a Knight of the Order of Poets, 1910, he said “no man can follow or share the religion of another. His religion, whatever it may be, is his own.” Jordan felt that religious groups could even be pernicious: “when organizations in the name of religion strive to resist the progress of knowledge and to punish or ostracize men and women who think for themselves and by the truth are made free, their influence is evil.”

For Jordan, “true religion concerns our relation to each other and to unseen and unmeasured powers surrounding us.” He was fond of saying that wisdom “consists in knowing what to do next, virtue in doing it;” and that religion “should provide a reason why.” In The Call of the Twentieth Century, 1903, he said that “those who control the spiritual thought of the Twentieth Century will be religious men,” but not in “the fashion of monks, ascetics, mystic dreamers, or emotional enthusiasts,” or active in discussing the “intricacies of creeds.” Instead, he believed that the religious expression of the new century would “deal with the world as it is in the service of ‘the God of things that are.'”

In the final paragraph of The Wandering Host, an allegory on the life of Jesus, Jordan encapsulates the convictions that guided his life: “Choose thou thine own best way, and help they neighbor to find that way which for him is best.”

Sources

David Starr Jordan Papers are in the Stanford University Archives, the Indiana University Archives, and the Swarthmore College peace collections. The Jenkin Lloyd Jones Collection, Meadville/Lombard Theological School Archives, Chicago Illinois contains correspondence with Jordan. Among Jordan’s more than 600 books and articles are “Agassiz at Penikese,” Popular Science Monthly (1892); The Care and Culture of Men: a Series of Addresses on the Higher Education (1896); Standeth God within the Shadow (1901); The Blood of the Nation: A Study of the Decay of Races Through the Survival of the Unfit (1902); The Philosophy of Despair (1902), retitled The Philosophy of Hope (1907); A Book of Natural History (1902); The Voice of the Scholar (1903); Life’s Enthusiasms (1906); The Call of the Nation: A Plea for Taking Politics Out of Politics (1910); Temperance and Society (1911); The Story of a Good Woman, Jane Lathrop Stanford (1912); The Friendship of Nations: A Story of the Peace Movement for Young People (1912); and Your Family Tree (1929). A complete list of his works is in Alice N. Hays, compiler, David Starr Jordan: A Bibliography of His Writings 1871-1931 (1952)

Jordan wrote an autobiography, The Days of a Man: Being Memories of a Naturalist, Teacher and Minor Prophet of Democracy Volume I, 1851-1899 and Volume II, 1900-1921 (1922). Edward McNall Burns, David Starr Jordan: Prophet of Freedom (1953) is a biography and a study of Jordan’s ideas. See also James Albert Woodburn, History of Indiana University (1940); Burton Dorr Myers, M.D., History of Indiana University Volume II, 1902-1937: The Bryan Administration (1952); Robert M. Taylor, Jr., “The Light of Reason: Hoosier Freethought and the Indiana Rationalist Association, 1909-1913,” Indiana Magazine of History (June 1983); Bruce Harrah-Conforth, “David Starr Jordan: His Three Lives” Indiana Alumni (October 1985); and Gayle Ann Williams, “Nonsectarianism and The Secularization of Indiana University, 1820-1891,” (Ed.D. dissertation, Indiana University, 2001).

Article by Gayle A. Williams

Posted April 22, 2005