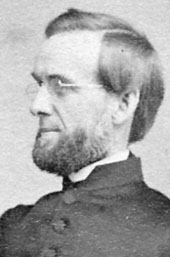

Arthur Buckminster Fuller (August 10, 1822-December 11, 1862) was a Unitarian clergyman who endeavored to give the Unitarian Church appeal to all social classes and championed the important liberal reforms of the day. As a United States Army chaplain, he accompanied Civil War soldiers into battle and lost his life to a cause in which he firmly believed. His older sister, Margaret Fuller, was a noted Transcendentalist, feminist, and writer. His grandson, (Richard) Buckminster Fuller, was an acclaimed twentieth-century architect, poet, author, and inventor.

Born in Boston, the fifth child of Congressman Timothy Fuller, Jr. and Margaret Crane, Arthur spent many of his formative years on the family farm in Middlesex County, Massachusetts. His father taught him to work hard, to take advantage of formal schooling, and to avoid violence, telling him that the pen wielded greater power than the sword. Only twice in his life did Fuller carry a weapon: while bird hunting at fifteen, his rifle misfired and severely injured his right eye; twenty-five years later, he was with the Union Army in the streets of Fredericksburg, Virginia.

In 1835, when Arthur’s father died of cholera, his overburdened mother passed the responsibility for raising him to his older sister, Margaret. She reluctantly put aside her budding literary career to attend to the family’s needs. She ensured that, in addition to working the family farm, Arthur got a proper education in Greek, Latin, literature, science, and mathematics. He had some home instruction and then attended Leicester Academy and Samuel and Sarah Ripley‘s school.

Fuller studied at Harvard, 1839-43. Because family finances had been strained since his father’s death, he taught at nearby schools to support himself. He became interested in ministry during his final year. Upon graduating in 1843, he traveled to Belvidere, Illinois where he ran a liberal academy. James Freeman Clarke had proposed that this might become the western Unitarian divinity school, but other influential Unitarians did not agree. In 1843 Fuller also became a lay preacher. His first sermon was at the First Unitarian Society in Chicago, Illinois. He itinerated over a wide area with his friend, Augustus Conant, who soon after became the minister in Chicago. While out west Fuller admitted that he missed his friends back east, but not their “staid habits.” He had become, he decided, too much of a westerner “to suit New England prejudices.”

Because of ill health, Fuller closed his school after 18 months. He returned east to study at Harvard Divinity School, 1845-47. After graduating he preached a few months at West Newton, Massachusetts, then served the Unitarian Society of Manchester, New Hampshire, 1848-53; the New North Church, Boston; and, beginning in 1859, the Unitarian Church of Watertown, Massachusetts. During those years he endured much heartache. His sister Margaret, her husband, and child drowned in an 1850 shipwreck. His wife, Elizabeth Davenport, whom he married in 1850, succumbed to cholera in 1856, leaving behind two children, Edith Davenport and Arthur Ossoli. His mother died three years later. Happily, he was remarried, to Emma Reeves in 1859. They had two children, Richard Buckminster and Alfred Buckminster.

To the consternation of many fellow Unitarian ministers, Fuller was an outspoken evangelist. Believing that workers, farmers, and other “common” folk would flock to Unitarianism if they received the word of God in their own simple language, he was an advocate of extemporaneous preaching. Members of various Christian faiths found his approach appealing. In 1859, for example, Debora D. “Mother” Taylor, wife of the eccentric Methodist Edward T. “Father” Taylor (the “Sailor’s Apostle”), attended one of Fuller’s services at New North Church. Afterward, she could not recall when she had more strongly “realized the presence of the Savior.” “I am glad others are going to heaven besides Methodists,” she rejoiced. “I doubt whether there could be any better doctrine that the Rev. Arthur Fuller gave us.”

Fuller vehemently defended Unitarianism against charges that it was subversive to true Christianity. He argued that, in contrast to Trinitarianism, his religion “requires every day to be a holy day,” and that salvation demands both faith in God and good works.

Fuller practiced what he preached. Abhorring drunkenness, he was active in the temperance movement. Against the wishes of many of his parishioners, he was an outspoken abolitionist, railing against the evils of slavery and the political forces that perpetuated it. He served on the Boston school board and advocated free public education for all children. Succumbing to the nativism of the mid-1850s, however, he published two sermons attacking the Roman Catholic Church. He sought to replace all “foreign” influences in Boston’s schools with Protestant teachings. He acknowledged it proper for women to pursue a professional career, allowing that many accomplished females had “not forgotten their sex, have not departed from its duties, but have nobly fulfilled them all, and are truly womanly women.” He honored the memory of his late sister by editing and republishing most of her works.

When the Civil War began, Fuller resigned his pastorate at Watertown to enlist in the Sixteenth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. As regimental chaplain, he realized the danger ahead. “I am willing to peril life for the welfare of our brave soldiery, and in our country’s great cause,” he wrote. “If God requires that sacrifice of me, it shall be offered on the altar of freedom, and in the defense of all that is good in American institutions.”

At first, the regiment saw little action. Fuller busied himself assisting in the post hospital, holding church services, and teaching reading and other lessons to foreign-born soldiers and escaped slaves. He loved his fellow soldiers and they admired him in return. His services drew congregants of every faith, including Roman Catholics, and they were so lively and well-attended that chaplains of other denominations, when going on leave, frequently asked him to substitute for them.

In March 1862, from a vantage overlooking Norfolk Bay, Fuller witnessed the battle between the Confederate ironclad, the Merrimack, and the much smaller Union ironclad, the Monitor. He wrote one of the most accurate, useful, and comprehensive of the eyewitness accounts. After fighting to a standoff, the Merrimack retired from the scene of battle, and Fuller rejoiced. “David had conquered Goliath with his smooth stones, or wrought-iron balls, from his little sling, or shot tower.”

When they were finally called to arms for the Peninsular Campaign in June 1862, the chaplain was pleased. “I know no holier place, none more solemn, more awful, more glorious, than this battlefield shall be.” For many days the Sixteenth Massachusetts was engaged in combat, their “baptism in blood,” as Fuller referred to it. Unlike some other volunteer chaplains, he went onto the battlefield with the men, shouting encouragement, leading prayers, and tending the wounded. When his battered regiment was withdrawn from the battlefield, he was so weak and ill that he was forced to return to Massachusetts. Throughout the summer his family feared for his life. Nevertheless, in October, in somewhat improved health, he set off to rejoin his regiment. He was warmly greeted by the combat-hardened men. “My own family could not be more cordial and more affectionate,” he reported.

As the regiment moved toward Fredericksburg, Fuller, under orders from the surgeon, remained behind. While recovering he ministered to the wounded in nearby hospitals. To his great disappointment, however, doctors soon declared him unfit for duty. “You can hardly realize the pain I felt when I found I could not share the field campaign without throwing away health and life,” he wrote his wife. He was consoled by the promise that an opening would be sought for him as chaplain of an Army hospital.

On Sunday, December 7, the regiment came together at the close of dress parade to hear their chaplain’s farewell address. Two days later Fuller wrote his wife that he was coming home, with no misgivings. “If any regret were mine, it would be that I am not able to remain with my regiment longer; but this is, doubtless, in God’s providence.” On December 10, Fuller was honorably discharged.

The following morning Fuller still lingered with his regiment, which was preparing to assault the city of Fredericksburg. Army engineers constructing pontoon bridges to cross the Rappahannock River came under heavy fire from Confederate sharpshooters. A call went out for volunteers to man boats for an assault on the enemy.

Fuller did not hesitate. Although no longer officially part of the Army, the frail, forty-one-year-old civilian climbed aboard a boat for the hazardous crossing of the river. Reaching the shore, he found himself with the Nineteenth Massachusetts Regiment, which was preparing to advance on the city. Captain Moncena Dunn of the Nineteenth later reported what happened to Fuller that day. “I saw him for the first time in the streets of Fredericksburg,” Dunn recounted. Fuller asked permission to join his unit. The captain replied that “there never was a better time than the present.” He ordered the chaplain to fill a place on the left of the skirmish line. “I have seldom seen a person on the field so calm and mild in his demeanor, evidently not acting from impulse of martial rage,” Dunn recalled. “His position was directly in front of a grocery store. He fell in five minutes after he took it, having fired [his rifle] once or twice.” Fuller had been killed instantly.

Later there was speculation as to why Fuller would risk his life to accompany the Nineteenth Massachusetts, which was not his regiment, into battle. The Nineteenth Massachusetts’ own chaplain had long since fled. He firmly believed that men deserved a chaplain by their side during a fight. He was a Unitarian who believed that salvation required faith and works, and he had many friends in the Nineteenth. It was his Christian duty to go with them.

Fuller’s funeral took place in Boston. The church was crowded with dignitaries, including the governor of Massachusetts. Ministers of several faiths eulogized him. James Freemen Clarke declared that “Arthur Fuller was, like most of us, a lover of peace, but he saw, as we have had to see, that sometimes true peace can only come through war. So he went, with a courage and devotion which all must admire, and fell, adding his blood also to all the precious blood which has been shed as an atonement for the sins of the nation. May that blood not be shed in vain.”

Clarke and his fellow mourners were certain that Fuller would long be remembered as a Unitarian minister of distinction. As the decades passed, however, the memory faded. Fuller stood outside of the social world inhabited by his sister, Margaret. He left behind relatively few writings, none of great consequence. Thomas Wentworth Higginson wrote in Harvard Memorial Biographies that the fallen chaplain had been a self-assertive, intensely earnest man, but who was “less gifted in intellect” and “less devoted to artistic culture” than his famous sister. Fuller served ordinary folk and related far better to farmers, artisans, shopkeepers, laborers and soldiers than he did to the intellectuals who preserved his sister’s memory.

Fuller wrote numerous letters to family and corresponded regularly with religious and secular newspapers from his days in Illinois until shortly before his death. The bulk of these are with the Fuller Family Papers at Houghton Library, Harvard University. While in the army he wrote for the Boston Traveler, the Boston Journal, the Christian Inquirer and the New York Tribune. He edited several of his sister’s works, including Woman in the nineteenth century (1855); At home and abroad; or, Things and thoughts in America and Europe (1860); and Life without and life within, or, Reviews, narratives, essays, and poems (1860). Among his few published works, worth noting are Discourse in Vindication of Unitarianism from Popular Charges Against It (1848); Liberty versus Romanism: two discourses, delivered in the New North Church (1859), and A Record of the First Parish in Watertown, Massachusetts (1861). Fuller also wrote “Historical Notices of Thomas Fuller and His Descendants,” originally published in the New England Historical and Genealogical Register (October 1859), reprinted as a book, with additions by his daughter Edith Davenport Fuller, in 1902. The only full-length biography, essentially a hagiography, is his brother Richard Frederick Fuller’s Chaplain Fuller, Being a Life Sketch of a New England Clergyman and Army Chaplain (1864). For critical assessments, see Thomas Wentworth Higginson, ed., “Arthur Buckminster Fuller,” Harvard Memorial Biographies, vol. 1 (1866); and “Arthur Buckminster Fuller,” in Samuel A. Eliot, ed., Heralds of a Liberal Faith, vol. 3 (1910). See also Charles Lyttle, Freedom Moves West (1952, new edition 2006).

Article by Joseph Herring

Posted October 17, 2006