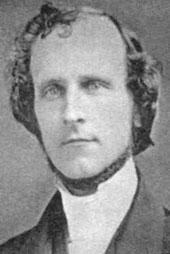

Charles Henry Appleton Dall (February 12, 1816-July 18, 1886), a Unitarian minister to the poor in the United States and an early Unitarian minister in Canada, was for three decades the only Unitarian missionary to India. He influenced and worked with the leaders of the liberal Hindu Brahmo Samaj movement and, controversially, joined the Brahmos himself. Working as an educator as well as a missionary, he helped foster the emergence of a class of liberal Hindus, as well-acquainted with Shakespeare and Milton as with their own traditional religious literature. His Unitarianism proved to be a safe and useful way for the young Bengali elite to step outside traditional patterns in order to critique Indian society and politics and to propose needed reforms. Although like most other missionaries of his time he made few converts to Christianity, his work did much to promote inter-faith dialogue and to prepare the way for modern India.

Charles was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the son of James Dall and Henrietta Austin. Henrietta was the daughter of a shipping merchant and the sister of Mary Austin Holley. Charles was sent to Boston at age six to study at the Franklin School, 1824-28, and Boston Latin School, 1828-33. He graduated from Boston Latin at the head of his class, distinguishing himself particularly in Latin, Greek, and mathematics. He lived in Boston with his father’s sister and brother, Sarah and William Dall. He did not visit his parents in Baltimore for nine years.

Dall attended Harvard College, 1833-37, graduating with Henry David Thoreau and Richard Henry Dana, and then the Cambridge (later Harvard) Divinity School, 1837-40. While attending college and divinity school, he directed the Sunday School at the Hollis Street Church, across the river in Boston. He was shaped by the liberal Christian piety and moderate social conscience of New England Unitarianism, as preached by William Ellery Channing. Modeling his own ministerial style after Joseph Tuckerman, minister-at-large to the poor of Boston, Dall learned to accentuate his own strength: bringing elementary, adult, and vocational education to the working classes.

Dall served fourteen months as minister-at-large, visiting and educating the poor, at William Greenleaf Eliot’s Church of the Messiah in St. Louis, 1840-42. Shortly after he was ordained there as an evangelist, in late 1841, he was forced to leave St. Louis for the sake of his health. He went to Mobile, Alabama for a short time, then, in 1842, took a ship to England, where he met many distinguished Unitarians, including James Martineau, and observed British Unitarian methods of social reform.

Back in America at the end of the year, he undertook another urban ministry—in Baltimore, 1843-45. He preached outdoors, visited prison inmates, and taught working-class children using advanced educational techniques. In 1844 he married author Caroline Healey, later a spokesperson for women’s rights. They had known each other since his days in Divinity school. They worked together at his ministry and Caroline briefly carried on single-handed after his health broke down again in 1845. While he was recovering in Boston, the first of their two children, William Healey Dall (1845-1927), later a distinguished naturalist, was born. In 1846 Dall attempted a third urban ministry in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, but it did not last the year, before funding was discontinued. A difficult personality and a tendency to take to bed when faced with criticism continued to limit Dall’s progress in the urban ministry. Furthermore, his specialized ministry did little to promote growth at the first three Unitarian churches with which he was associated.

Dall next had two regular parish ministry settlements, in Needham, Massachusetts, 1847-49, and in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1850-54. He resigned from Needham under pressure from his congregation, who found him too authoritarian and did not like his reform activities. As usual the stress caused his health to collapse. In Toronto, following the ministry of William Adam, who had been a Scottish missionary to India, Dall had his longest and most successful North American pastorate, bringing about growth in numbers and activity in the congregation. Although he enjoyed considerable support among the members of the church, a disagreement with Joseph Workman, the founder of the congregation, over the financing of a new church building led to his resignation and yet another illness.

In late 1854 Dall moved with his family to Newton, Massachusetts. While recovering there, he heard of the report to the American Unitarian Association (AUA) of Charles T. Brooks, who had just returned from a visit to India, calling for a Unitarian mission to the subcontinent. Dall’s career changed dramatically in 1855, when he applied for and was appointed by the AUA to the proposed mission in Calcutta. Among other tasks, he was to establish this mission, investigate the Hindu Brahmo Samaj (“Society of Vedantists”), and to travel to Madras to follow up Brooks’s findings about the Unitarian congregation there. Dall’s brief was to provide religious education while avoiding controversy and polemics. During the journey to Calcutta, he was extremely ill. On arrival he was so weak that he had to be carried ashore in a litter. In spite of this, he had the strength to write the AUA just before landing and then again two weeks later. Whatever had caused Dall so much physical suffering in New England quickly disappeared in the tropical humidity of Calcutta.

Caroline Dall and the children remained in America. Charles returned to America and visited his family just five times during his thirty-one year ministry in India: in 1862, 1869, 1872, 1875 and 1882. Charles and Caroline had not been happy in their decade together: he had been a financial and emotional burden to her. Separated by half the earth, their individual careers began to blossom.

Dall’s letters, reporting his progress to the AUA, were published quarterly until 1866. Within a month after his arrival he founded a “Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in India” and a congregation made up of British and American residents of Calcutta. “Some Hindoos of education, and a few of the Society of Rammohun Roy, attend,” he wrote, “and also meet me during the week for conversation.” To the Hindus who visited he gave books by Channing, Eliot, James Freeman Clarke, and other American Unitarians.

He proclaimed his Unitarian theology to his Calcutta audience in a series of lectures, Some Gospel Principles, 1856. In “Christian Liberty” he stressed the significance of dissent in religious history. His model heroes of dissent included four American Unitarian reformers, Henry Ware, Tuckerman, Channing, and the pacifist Noah Worcester. Although his mission to India grew out of the same New England merchantile trading contacts which had fueled Ralph Waldo Emerson’s fascination with the East, Dall was not a Transcendentalist. His Christology resembled that presented by Channing in “Likeness to God.” He argued that Christ’s relation to God is that of a reflector of God’s mental and moral likeness, analogous to the likeness of a child to his father. Rejecting the doctrine of atonement as “heathen,” he set forth the morals of Christ and the sense of human brotherhood as the keys to salvation.

In these lectures, as part of his invitation to Hindus to receive the precepts and parables of Jesus, Dall invoked the name of Rammohun Roy, founder of the Brahmo Samaj and the first Hindu to discuss the Gospels. By emphasizing the connection between Rammohun Roy and Jesus, however, Dall offended both orthodox Christians and the Brahmo leader Debendranath Tagore, who told him that “he would not hear the name of Jesus spoken in the Samaj.” In 1857 Tagore informed Dall that he was no longer welcome even to visit the Calcutta Brahmo Samaj. In order to reach the more liberal Brahmos, in 1857 Dall founded the Rammohun Roy Society (later called the Hitoisini Sabha, or Association).

In the Hitoisini Sabha, Dall promoted the reading of Channing and Theodore Parker. Though he did not sympathize with the views of Parker, Dall considered that Parker’s works “well meet a transition state of mind between Hindooism and Xty.” His students, however, picking up on Parker’s idea of the “transient and permanent” in religion, often came to classify Dall’s particular religion among the transient forms. They thought his claim to be both a Unitarian and a Christian inconsistent. They could not understand why, if he disbelieved in Christ’s divinity, he still believed in the miracles of Christ, like the other Christian missionaries they knew.

Dall promoted Bengal nationalism, and criticized the rich landowners and the caste system. In order to reach his audience better, he set about learning Bengali, Hindustani, Tamil, and Sanskrit and studied the Bhagavad Gita. As his critique of British rule in India alienated the European community in Calcutta, his British-American congregation withered away. This forced him to concentrate more on his young Bengali proteges.

The effect Dall had on Indian culture and religion was within an Indian context. It did not translate into measurable Christian missionary success. In his 1863 report to the AUA he talked only of “Hindoo Unitarian sympathy” and of how “We are making Unitarians or say Unitheists, out of polytheists.” He struggled against the Hindu and Buddhist tendencies to think of God impersonally. In an article, “The Personality of God,” published in the South Indian paper, the Crescent, he wrote, “I am a person, because I feel and trust and think and act, and year after year I am the same I. If God gives these powers, he has them to give. God feels and trusts and thinks and acts, and forever is, at least, as able as his creature. If I am a person, he, too, is a person—the infinite I AM.”

During the 1860s Dall became closely affiliated with the new Brahmo leader, Keshub Chunder Sen (1838-1884), whose ideas of Christianity were mediated by reading Channing and Parker. In 1866 Keshub split away from Tagore’s more narrowly Bengali and anti-Christian Adi Brahmo Samaj and formed the Brahmo Samaj of India. In 1870, on tour in England, Keshub claimed that “We Indians attach a far greater importance to righteous life than pure doctrines.”

Although Dall understood what motivated the Brahmos to avoid the Christian label, he couldn’t understand why Keshub would use the figure of Christ so freely in his teaching, and still refuse to identify himself with Unitarian Christianity. Dall thought that the only way to get Keshub to understand and accept his point of view was to become a part of the Brahmo movement and work from the inside. Accordingly, in 1871, he joined, calling himself “a Brahmo follower of Christ.” Severe criticism of Dall appeared in American Unitarian and English language Brahmo publications. The Brahmo Indian Mirror wrote, “In one of his lectures just published, he attempts to show that both the present leader of the Brahmo Samaj as well as the founder of that institution view Christ in the same light as Mr. Dall himself. If Mr. Dall intends to preach Unitarian Christianity under the assumed name of theist or Brahmo let him do so on his own account and not on that of Baboo Keshub Chunder Sen or Rajah Ram Mohun Roy.”

The Brahmo Samaj split again in 1878 when Keshub, apparently against his religious principles, arranged for his underage daughter to marry the Maharajah of Kuch Behar. Those opposed to Keshub formed the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj, while Keshub reorganized his supporters as the Church of the New Dispensation. Dall was shocked by his associate’s behavior and, by this time, Keshub was also disillusioned with Dall. In 1883 Keshub was quoted as saying, “[Unitarianism’s] representative in Calcutta has made it ridiculous here.” Despite this, in 1884 Dall was the only non-Hindu present at Keshub’s deathbed.

Around 1880 Dall received a letter from Hajom Kissor Singh, leader of what would become the Khasi Hills Unitarian movement. Although Dall was unable to make a trip to Singh’s remote location, he was able to send books and their correspondence bore fruit in the journey of Jabez T. Sunderland to the Khasi Hills ten years after Dall’s death.

During his later years in India, as Dall had less and less influence over the liberal Hindu religious reform movement, he concentrated more on general education. In 1860 Dall had founded in Calcutta the School of Useful Arts. When it began there were seven students; a year later there were nearly 300. This was a continuation of the interest he had shown in America in elevating the working classes through practical education. He also came to manage the Rover’s School for Poor Boys, the AUA’s Hindu Girl’s School, and the Hayward School for Girls.

Dall remained in India the rest of his life. He died during gall bladder surgery in 1886. Services were held for him by both the Christians and the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj. The Sanskrit inscription on his grave reads, “Though that high-minded philanthropist of benign appearance, who was, as it were, an ocean of good qualities, who knew all the principles of religion and science, and who was of pure morals and a defender of the true faith, lies dead in this grave, yet he may truly be said to live in the tangible proofs of his goodness.”

Sources

Dall’s papers are in the Archives at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His letters to the AUA and his personal papers from both his American and Indian careers are in the Harvard Divinity School’s Andover-Harvard Theological Library. Various letters from India were published in the AUA Quarterly Journal, and in Dall’s Twenty-Five Years: General Report of the Indian Mission of the American Unitarian Association (1880). There is correspondence of the Dall family in the Hay Library in Providence, Rhode Island. Dall’s writings include Patriotism in Bengal (1858), “Philosophy of Conscience” (1858), From Calcutta to London by the Suez Canal (1869), Lecture on Rajah Rammohun Roy (1871), The Theist’s Creed (1872), and What Is Christianity? Sonship to God (1883). Early biographical treatments include John Healy Heywood, Our Indian Mission and Our First Missionary (1887); Henry Williams, Memorials of the Class of 1837 of Harvard University (1887); and Caroline Dall, ed., Memorial to C.H.A. Dall (1902). See also Spencer Lavan, Unitarians and India (1977); Phillip Hewett, Unitarians in Canada (1978); Asoknath Mukhopadhyay, “Reform from Within and the Instrumentality of Dall’s Calcutta Mission: Initial Phase, 1855-58,” in Bengal, Past and Present (July-December 1980); and Susan S. Bean, Yankee India: American Commercial and Cultural Encounters with India in the Age of Sail, 1784-1860 (2001). There is an entry on Dall, by Robert A. Schneider, in American National Biography (1999).

An early review of Dall’s work in India can be found in George Leonard Chaney, “The India Mission,” in the 1872 Report of the National Conference of Unitarian and other Christian Churches.

Also useful is the biography of Charles Henry Appleton Dall in Samuel A. Eliot, ed., Heralds of A Liberal Faith: The Preachers, Volume 3 (1910).

Article by Spencer Lavan and Peter Hughes

Posted August 20, 2006