Caroline Bartlett Crane (August 17, 1858-March 24, 1935) was a Unitarian minister, suffragist, civic reformer, and social gospel advocate. Among the first wave of American college-educated women, she broke gender barriers as a journalist, newspaper editor, and minister before leaving the ministry to develop a new career as a “municipal housekeeper”—applying “womanly” principles of housekeeping to the public sphere. She became known as “America’s housekeeper.”

Caroline (“Carrie”) Julia Bartlett was born to Lorenzo Bartlett and Julia Brown in Hudson, Wisconsin, about twenty miles east of St. Paul, Minnesota. Her father, a Mississippi riverman, taught her to read by age four and encouraged her scholarly development. When her twin infant sisters died, her parents became skeptical of religion and left the Methodist church. In spite of their doubts, they sent Carrie and her younger brother Charles to a Congregational Sunday school. She took her biblical studies seriously but questioned the portrayal of God as cruel and unjust. By the age of twelve she had rejected the standard Protestant teachings of sin and salvation.

After a year in Le Claire, Iowa, the Bartlett family moved to Hamilton, Illinois. Carrie’s aunt, Abigail Haskins, introduced her to Universalism and told her stories about the strong-willed and independent women in the family. At Hamilton she made friends with Mary Safford and Eleanor Gordon, two older neighborhood girls who later went on to become Unitarian ministers. Entranced when she heard Unitarian minister and Iowa Unitarian Association field officer Oscar Clute preach a sermon on the evolution of religion, Carrie told her father that she had decided to become a Unitarian minister. He insisted that she drop the idea without further discussion.

Although Carrie had not graduated from high school, her father convinced Carthage College to accept her as a student. Once there, she persuaded school officials to let her take the full classical course of study, including the Greek she felt she needed for seminary. She stood up for her liberal religious views, challenging the conservative Lutheran faculty’s criticism of Thomas Paine. She graduated in 3 years—as valedictorian.

Carrie could not attend Meadville Theological Seminary as scholarships for women were not available and her father refused to assist. Instead, she worked for a year as a school principal in Montrose, Iowa, 1879-80. She then became a reporter with the Chicago Telegraph. In 1883 she moved with her parents to St. Paul, where she contributed freelance articles to the Pioneer Press. She reported on trials, fires, and politics for the Minneapolis Tribune, 1883-85. She refused to write for the newspaper’s society pages and often carried a pistol for protection when on late night assignments. She saw reporting as an alternative to ministry; it was another way of bettering society. Capping her newspaper career, she worked as the city editor for the Morning Times of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, 1885-6.

While in Minneapolis, Carrie shared her dreams with Unitarian minister William Channing Gannett, who guided her independent study. When she left Oshkosh, she spent eight months living in Dakotas with her widowed father. With his blessing, she reflected on theological issues and wrote sermons, which she sent to Oscar Clute and other minister friends to critique. In 1886 the Iowa State Unitarian Conference accepted her as a candidate for ministry.

In 1887 Carrie was called by a congregation in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, which had recently been founded by Eliza Tupper Wilkes. She rented a meeting place, started a church school, and shifted the congregation’s priorities to outward-focused ministry, placing them in the vanguard of the Social Gospel movement. By the end of the year, the Sioux Falls Unity Church was worshipping in a new and modern stone church. After two years the membership had risen from 70 to 250. Unfortunately this full-time ministry prevented Carrie from pursuing her ministerial studies. In 1889 she resigned to attend Chicago Theological Seminary.

John Effinger of the Western Unitarian Conference suggested Carrie take over preaching at the troubled Kalamazoo congregation on the weekends while attending school in Chicago. Although the Kalamazoo congregation was not initially happy with the idea of a woman minister, her command of the pulpit won them over and they called her to be their minister. She was soon ordained. Clute preached the ordination sermon. To reflect her new status she decided in future to go by the more formal name, Caroline.

Caroline revived the Kalamazoo Sunday school program, which soon increased the overall church membership. Once again, however, her pastoral duties kept her from her studies. She was unable to attend her weekday seminary classes. The next fall she began preaching half-time at the Grand Rapids congregation, while Marion Murdock joined her as co-pastor of the Kalamazoo church (a common arrangement among the group of liberal women ministers that came to be known as the “Iowa sisterhood”).

At the end of 1890 Caroline left her pastorate to travel in Europe. In England she became interested in the social activism of the Salvation Army, having met its founder General William Booth and talked with many of its leaders. Because of the resignation of Murdock, Caroline was soon called back to serve in Kalamazoo. Her liberal theology had by this time matured; her sermons and writings began to reflect a wider and deeper experience. Her practical ministry focused more on social issues.

Unhappy with the Kalamazoo church building, Caroline designed a new church to meet the needs of a growing congregation and to provide spaces for programs for social improvement. She replaced the old-fashioned “theological church,” designed to be a house of God, with a “sociological institution” that would house God’s people. She got the congregation to change its name to “People’s Church” and to become nonsectarian, no longer calling themselves Unitarian. In spite of these changes, the church did not break its ties to the Western Unitarian Conference.

Caroline believed that a “church cannot be a place where we . . . come together once a week and enjoy our doctrine and congratulate ourselves that we have a faith free from superstition. We must do something for others, as well as for ourselves. And the more we have done for others, the more in the end, we shall find we have done for ourselves.”

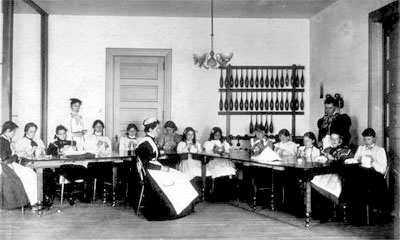

Between the dedication of the new building in 1894 and the end of 1897, the congregation established many community programs including a free public kindergarten, a women’s gymnasium, household science classes, manual training classes, and a literary group for blacks called the Frederick Douglass Club. In 1897 over 100 meetings a month were held at the church. Caroline taught a class on Eastern religions. She employed her journalism background to promote these programs and the church. After Colonel Robert Ingersoll, the great agnostic, visited People’s Church, the Chicago newspapers reported him saying, “If all churches were like this, I would never say one word against them or religion.”

Caroline was active outside the church as well, working with the Twentieth Century Club, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and serving on the board of the Michigan Equal Suffrage Association. In 1891 she delivered the closing sermon at the National American Woman Suffrage Association in Washington, D.C. She also used her position as a religious leader in state politics, lobbying against the death penalty and campaigning for change in the local poor relief system.

In the summer of 1896 Caroline took graduate classes in sociology at the University of Chicago. She returned to Kalamazoo with new ideas for the extension of her community ministry. She started a Unity Club for the study of local sociology. Club members prepared a survey of the city and investigated and reported on specific topics such as the food supply and health services. They offered city officials and others use of this information to make more rational decisions on community improvements.

At the 1896 church New Year’s Eve reception, Caroline surprised her congregation by marrying Augustus Warren Crane, a physician and innovator in radiology. Ten years her junior, Warren not only supported her work, but also enjoyed having a wife in the public eye. His medical training and knowledge of bacteriology later proved helpful in her sanitation surveys.

While covering the 1895 National Woman Suffrage Association convention held in Minneapolis, Caroline had become acquainted with Susan B. Anthony. Upon hearing of Caroline’s marriage, Anthony warned, “Either the home or Profession—or most likely both suffer.” Events at first appeared to bear this out. A year after her wedding, Caroline announced that she was leaving her pastorate to further study sociology. After she resigned in 1898, however, ill health forced her to take a two-year break from any work. Upon recovery, Crane shifted entirely from ministry to social reform. She remained a member of the People’s Church all her life, serving on committees, teaching Sunday School, and attending every annual meeting. She also served as a guest preacher.

In her new role as wife Caroline had begun to pay more attention to her household. As a girl she had paid little attention to domestic matters. She had started her church’s school of household science partly in response to her own need to learn domestic skills. She now called herself a municipal housekeeper, considering her work an extension of woman’s domestic sphere into a larger political context. She belonged to the camp of woman’s rights advocates that saw women as having unique gifts that could be used to improve both the family and society. Her concern for the health of the local meat supply (she was herself a vegetarian) sprang from the need to serve safe food to her family.

Crane invited prominent citizens to accompany her, unannounced, to a local slaughterhouse. They observed unsanitary conditions similar to those described later in Upton Sinclair’s 1906 book, The Jungle, and found that many of the animals were riddled with tuberculosis. She marshaled public pressure, including newspaper reports, to encourage butchers to voluntarily make reforms. Eventually she was invited to the state capital, Lansing, where she helped write and pass meat inspection legislation.

When she discovered that federal inspection laws were being violated, Crane exposed the corruption within the Department of Agriculture—first going to the American Public Health Association, where her effort was blocked, and then to a Congressional hearing, where the officials under scrutiny tried to discredit her via personal attacks. She took her message to the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, addressing groups across the country. In 1913 her findings were published in the muckraking Pearson’s Magazine.

During this same period, Crane was becoming known nationally for her public health surveys. She worked with local women’s groups in over sixty cities nationwide. Politicians and their wives were invited to personally inspect their city’s water and sewer systems, food supply, garbage collection and disposal, street sanitation, and other public institutions. She would give a public report at the end of the survey and follow up with a written report.

Throughout these public struggles Caroline was sustained and supported by her husband. They built a cottage retreat, “the Brown Thrush,” on Gull Lake, and spent much time alone there. Unable to conceive, they adopted two children, Bartlett and Juliana, in 1914. Over the next few years, although she spent much of her time with her children, she continued to conduct an occasional public health survey.

In 1917, as the United States entered the First World War, Crane was appointed president of the Michigan Woman’s Committee of National Defense. She focused the Committee’s efforts on food conservation and production.

In the 1920s Crane wrote for, and edited, The Woman’s Journal. Her main interest then was in housing reform. There was a shortage of working class housing suitable for raising a family. In 1924 her house design, an affordable “Everyman’s House” centered on the needs of a mother with an infant, won a contest sponsored by the Better Homes Committee. Nationally known as a housing expert, she published a book about the project, Everyman’s House, 1925.

Crane was a dynamic organizer, speaker, and social reformer whose career epitomizes the Social Gospel movement. With her confidence, personality, and drive, she overcame gender barriers in the various phases of her career. She personally enjoyed having a high profile. She died at home in 1935 after suffering a stroke.

Sources

Correspondence, speeches, sermons, articles, travel journals, scrapbooks, autobiographical material and photographs are housed in the Caroline Bartlett Crane collection in the Western Michigan University Library. The biography, A Just Verdict: The Life of Caroline Bartlett Crane (1994) by Rickard O’Ryan is the primary biographical resource while Caroline Bartlett Crane and Progressive Reform (1999) by Linda J. Rynbrandt covers her reform career with emphasis on academic sociology from a feminist perspective. Crane was profiled during her lifetime in two books; American Women in Civic Work (1915), by Helen Christine Bennett and Occupations for Women (1897), by Frances Elizabeth Willard. Two local histories, People’s Church during the Golden Era of Caroline Bartlett Crane (1978) by Martha M. Fulford and The History of the People’s Church from 1889 to 1898 (1952) by Robert Ketcham provide details of Crane’s ministry in Kalamazoo. Secondary sources include Cynthia Grant Tucker, Prophetic Sisterhood: Liberal Women Ministers on the Frontier, 1880-1930 (1990) and Charles H. Lyttle, Freedom Moves West: A History of the Western Unitarian Conference 1852-1952 (1952, rev. ed. 2006). The web sites of the Kalamazoo Public Library and the Kalamazoo People’s Church are also useful.

Article by Renee Zimelis Ruchotzke

Posted February 24, 2007