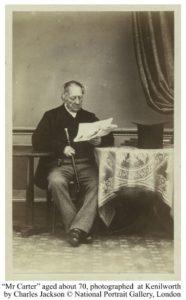

Samuel Carter (May 15, 1805-January 31, 1878) was a lawyer who shaped the legal codification and business practices of the early railways in England. For nearly four decades he was solicitor to two of the corporations that created Britain’s rail network. He was a lifelong Unitarian, a faith many of his forebears had embraced during the Midlands Enlightenment and Britain’s Industrial Revolution. Late in life he briefly represented his native city of Coventry in Parliament, a task he regarded as the “crowning honour” of his life.

Samuel Carter (May 15, 1805-January 31, 1878) was a lawyer who shaped the legal codification and business practices of the early railways in England. For nearly four decades he was solicitor to two of the corporations that created Britain’s rail network. He was a lifelong Unitarian, a faith many of his forebears had embraced during the Midlands Enlightenment and Britain’s Industrial Revolution. Late in life he briefly represented his native city of Coventry in Parliament, a task he regarded as the “crowning honour” of his life.

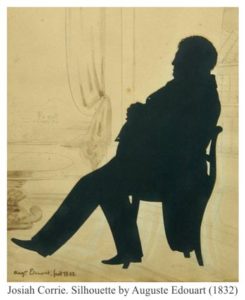

Samuel’s mother Jane was the daughter of Josiah Corrie Sr., a dissenting minister at Kenilworth in England’s Midlands, who had trained at the Carmarthen Academy. His father, also called Samuel Carter, and his family were prominent in the affairs of nearby Coventry. Samuel Sr. was the county prison keeper for over three decades, so the family lived in an imposing home on the prison grounds. In later years Samuel’s mother was employed as matron. His father was also a manager of Coventry’s charity payments, commissioner of the Street Act to improve the roads and, being a “staunch Unitarian”, served as chairman of the Great Meeting in Smithford Street. Samuel’s grandfather had served as mayor while his uncle John Carter was town clerk and solicitor for many years.

Carter was educated near Birmingham at the school of his uncle John Corrie, who was a Unitarian minister. On August 3, 1821 he was formally articled to another uncle, Josiah Corrie – a solicitor in New Street, Birmingham – and he qualified for his profession in 1827.

His upbringing amongst these relatives influenced Carter’s character and values. They would become “the secret of his eminence”. His uncle, Coventry town clerk John Carter — who is considered to be the model for the character Frank Hawley in George Eliot’s Middlemarch — adeptly orchestrated administrative and political matters to suit the municipal officers, at a time when Coventry (like many other towns) lacked governance accountability. Samuel Carter himself “was not a man to be outwitted”. According to the Solicitors’ Journal, he showed “extraordinary shrewdness”, was “a tactician of renown” and “a doughty Politician”. On the other hand, he also had “great general intelligence and cultivation, and formed many friendships in the world of literature, science, and art”. “He was a great reader”, with his favourite authors including the philosophers Baruch Spinoza and Joseph Butler – tastes encouraged by Uncle John Corrie, who was a Fellow of the Royal Society and president for many years of the Birmingham Philosophical Institution.

Embracing his uncle Josiah Corrie’s professional ethos, Carter was “a very worthy man, courteous and gentlemanly in his manners, even in his political conflicts”. Like numerous other Unitarians of the period, he worked hard, guided by “a spirit of determination” and “strict sense of integrity” to achieve personal success while also benefiting humankind and helping those less fortunate. His father had similarly “always been so ready to aid in every good work”. Finally, he was “plain in attire, and plain-spoken in address”, talked quietly, but showed an “archly playful manner” when circumstances allowed, including in the witness box. Obituaries for Carter emphasised this “very unusual combination” of qualities: “His geniality and open handed generosity were, indeed, as remarkable as his hard-headed sagacity”.

Carter married Maria Ronalds in 1833. She was Sir Francis Ronalds’ sister and had been christened by Thomas Belsham at the Gravel Pit chapel in Hackney, London. A year older than Carter, she had already helped Frances “Fanny” Wright muster support for her abolition experiment at the Nashoba Colony near Memphis, Tennessee. She had also established an early infant school with her sister. Their families had been connected for years: Revd Josiah Corrie’s sister had married Maria’s great-uncle, and John Carter had articled her cousin and married her second cousin. Carter and his wife would worship at the New Meeting in Birmingham where Samuel Bache was minister and at least one of their children boarded at his school. Reflecting their parents’ talents, two of their sons and their son-in-law became barristers while their other son Hugh was an artist.

Carter married Maria Ronalds in 1833. She was Sir Francis Ronalds’ sister and had been christened by Thomas Belsham at the Gravel Pit chapel in Hackney, London. A year older than Carter, she had already helped Frances “Fanny” Wright muster support for her abolition experiment at the Nashoba Colony near Memphis, Tennessee. She had also established an early infant school with her sister. Their families had been connected for years: Revd Josiah Corrie’s sister had married Maria’s great-uncle, and John Carter had articled her cousin and married her second cousin. Carter and his wife would worship at the New Meeting in Birmingham where Samuel Bache was minister and at least one of their children boarded at his school. Reflecting their parents’ talents, two of their sons and their son-in-law became barristers while their other son Hugh was an artist.

Carter’s uncle Josiah Corrie had conducted the small-scale business typical of provincial solicitors, but that quickly changed as rail transport developed in Great Britain. Carter was 25 when they entered into partnership in 1830, coinciding with their appointment as solicitors to the London & Birmingham Railway (L&BR). This was to be the first intercity line for the metropolis.

The London & Birmingham Railway was a project of unprecedented scale and complexity, promoted and funded by industrial capitalists to facilitate their trade but quickly seen to foster regional development and a new way of life founded on mobility. Early legal activities focussed on the purchase of shares; providing project details to counties and the 265 parishes and townships along the route; negotiating all land access, purchase and recompense, and documenting the agreements; preparing the private bill to obtain an Act of Incorporation for a joint stock company and instructing counsel for its hearing in parliament; and legal arrangements for the new company.

The bill passed through the House of Commons committee in 1832 but was rejected by the Lords to protect gentlemen whose estates would be “cut up”. A year later, after further “compensation” of landholders, it was approved. Construction cost £5.5 million and employed 20,000 men under the oversight of engineer Robert Stephenson. The entire railway was open by September 1838 with George Carr Glyn as chairman.

The L&BR now having operations as well as development arms brought additional legal responsibilities both at corporate level and for the business. Carter contributed to board meetings and there were ongoing parliamentary bills. Representation of the company at accident inquests, and defending or prosecuting employees, followed in part from immature safety systems and inexperience in running and using the new mode of transport. Carter himself was charged with perjury in relation to a property acquisition, although he was quickly acquitted. He left the “crowded Court” “amidst the congratulations of his friends” including Glyn, other railway chairmen and directors, parliamentary members “and many other gentlemen of Birmingham”.

As the financial and social benefits of railways became clearer, other communities wished to participate and the L&BR encouraged these expansion opportunities. Lines were quickly built to connect towns around the route and to the north of England with the arterial to London. The collaborative relationships put in place by the L&BR ranged from running powers to purchase and all required legal definition. Carter was solicitor to many of these new railways, even when they were separate entities. Acting as “legal guide”, he shared his broad experience of the industry with the directors of these railways and thereby ensured conformity with the trunkline.

As the financial and social benefits of railways became clearer, other communities wished to participate and the L&BR encouraged these expansion opportunities. Lines were quickly built to connect towns around the route and to the north of England with the arterial to London. The collaborative relationships put in place by the L&BR ranged from running powers to purchase and all required legal definition. Carter was solicitor to many of these new railways, even when they were separate entities. Acting as “legal guide”, he shared his broad experience of the industry with the directors of these railways and thereby ensured conformity with the trunkline.

One of these early projects was the Birmingham & Derby Junction Railway (B&DJR), to which Corrie & Carter was appointed the sole solicitor in 1835. Carter inspected the proposed route with the surveyor George Stephenson, the “Father of Railways”, and both it and a rival line were sanctioned the next year. The B&DJR chairman and Carter broached an agreement with the rival company just before its line opened, but without success. A rate war ensued and fares were slashed to attract customers, in the first of what would be innumerable instances of duplicate and competing operations across the emerging railway network. Only maximum charges per mile were stipulated in B&DJR’s act but legislation was now moving towards uniformity in rates and a homogeneous system. The B&DJR was therefore taken to court but Carter illustrated “the power of modifying our rates” to parliament in 1840. The standard clause in future acts allowed fares to be varied to suit “the circumstances of the traffic”.

Another early issue was how to enable passengers and goods to traverse independent lines – ideally on a single ticket without changing trains. The B&DJR experienced difficulties using L&BR’s Birmingham station so Robert Stephenson and Carter, being part of both companies, apparently promoted to their directors the importance of establishing a process that facilitated through traffic and allocated the revenue across the companies. The L&BR and the B&DJR were founder members of the Railway Clearing House and George Carr Glyn was its chairman when it opened at the beginning of 1842. It remained in operation until the railways were nationalised after World War II.

Meanwhile, B&DJR’s poor profits could not long continue and in 1843 “the arguments of the Chairman and Mr. Carter” at the shareholders’ meeting swayed them to join with their rival company. This first significant consolidation in Great Britain’s railroad sector created the Midland Railway (MR). The “Railway King” George Hudson was appointed chairman and for a short while it was the largest of the rail networks. The MR achieved significant operating efficiencies.

Carter’s law partner and uncle, Josiah Corrie died in early 1842. Carter was in the “remarkable position” of being solicitor for two major corporations and he retained this dual role for nearly 20 years. Having key advisory responsibilities with both organisations, they stated publicly that he “enjoys the fullest confidence” of their chairmen. As the Solicitors’ Journal noted, his “influence in the development of the railway system will, probably, never be fully appreciated”. Fortunately “his capacity for work and clearness of head were marvellous” because his job was enormous. In November 1845 his name was on 43 detailed notifications for bills about to be lodged in parliament – evenly spread across the MR and the L&BR. The MR remunerated his firm £19,060 for the session, of which 17% was fees for counsel, and Carter often accepted part of his payment in company debentures. In one session he paid counsel fees of £40,000. As “the principal legal officer of the company”, Carter then “had charge of all the Midland Bills in Parliament, and… it is said that he never lost a Bill” (the same could not be said of L&BR which became a more aggressive company).

Carter’s law partner and uncle, Josiah Corrie died in early 1842. Carter was in the “remarkable position” of being solicitor for two major corporations and he retained this dual role for nearly 20 years. Having key advisory responsibilities with both organisations, they stated publicly that he “enjoys the fullest confidence” of their chairmen. As the Solicitors’ Journal noted, his “influence in the development of the railway system will, probably, never be fully appreciated”. Fortunately “his capacity for work and clearness of head were marvellous” because his job was enormous. In November 1845 his name was on 43 detailed notifications for bills about to be lodged in parliament – evenly spread across the MR and the L&BR. The MR remunerated his firm £19,060 for the session, of which 17% was fees for counsel, and Carter often accepted part of his payment in company debentures. In one session he paid counsel fees of £40,000. As “the principal legal officer of the company”, Carter then “had charge of all the Midland Bills in Parliament, and… it is said that he never lost a Bill” (the same could not be said of L&BR which became a more aggressive company).

During the “excitement” of the parliamentary session, which “had always been the scene of his most anxious labours”, Carter was at Westminster with “control and direction” of his bills. He also raised petitions against competing bills and argued them in committee and was “in watchful attendance” in yet other committee rooms to ensure there were no potential issues. It was a fluid process and Carter and others would negotiate in the ante-rooms and corridors, delving into the minutiae of particular clauses while adjusting their case strategy to achieve the company’s overall goal. Needing to be abreast of all aspects of each project, Carter was once accused by opposing counsel of “giving evidence as an engineer”. Another complained: “You have not answered my question nor within a mile of it” as Carter’s wily character surfaced under cross-examination.

He was aided by an increasing number of clerks in his firm. Carter “watched carefully after their interests” “and he believed… he received a corresponding benefit”. A story survives that “he gave one of his clerks… a very large sum of money as a marriage portion” and he continued to support the families of other employees after their death. “Such kindness of heart” was “rare” in the period but aligned with his Unitarian faith.

One of Carter’s successful bills in the 1845-6 parliamentary session enabled the amalgamation of the L&BR with other companies to form the London & North Western Railway (L&NWR). Carter’s other major client was again Britain’s largest railway. By this time, he had opened a second office in Great George Street, London, close to parliament and L&NWR’s headquarters. His Birmingham business, which had moved to Waterloo Street after Josiah Corrie’s death, remained convenient for MR’s head office in Derby. Carter and his wife Maria still lived in Islington Row, Birmingham, although they later acquired a London property just north of Hyde Park from where they attended the Essex Street chapel during Thomas Madge’s ministry.

The interests of the two major railways were quite commonly aligned and Carter could represent them jointly at public meetings and elsewhere. He became “well known throughout the country” and his entering a railway station “calls forth the attention of every guard and every porter”. Also the subject of some snide remarks in the trade press for being “so frequently in print”, it was once suggested sardonically that Carter and his legal colleague should perhaps be the chairmen of L&NWR.

The third major company was the Great Western Railway (GWR) that linked London with the south west. The GWR’s engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel had chosen broad gauge (7 feet) for his tracks, while the other companies had positioned the two rails closer together; any interconnection between them thus required the time-consuming transfer of all people, animals and goods between carriages. Bringing compatibility to the national network became a prolonged, bitter and wasteful fight for supremacy.

The “Battle of the Gauges” was a significant feature of the frenetic 1845-6 parliament and it centred particularly on the broad gauge Birmingham & Oxford Junction Railway (B&OJR). Carter instigated detailed negotiations with Brunel in early 1846, whose correspondence indicates that he respected Carter’s ability to broker a lasting settlement. According to Carter’s “most sensible, practical, and straight forward letter”, they agreed a territorial boundary between their respective operations and joint leasing of the B&OJR that would cross it, but it was apparently negated by GWR’s affiliates. Carter then fiercely opposed the B&OJR bill and admitted to his good friend Robert Stephenson “Well, we are beaten” when it was sanctioned later that year. At the same time, however, the Gauge Act also became law. It specified 4 feet 8-1/2 inches as the standard gauge for future railways – including the B&OJR.

In “as pretty a move as is to be found in the history of British Railways”, friends of the narrower gauge – including Carter – immediately bought up most of B&OJR’s shares on the market, and the L&NWR and MR directors began attending its proprietors’ meetings, along with Carter who “gave advice” to the spokesman for the new shareholders. Attempts to form a relationship with L&NWR were blocked in the courts, so B&OJR needed to stay with GWR. A further act in 1848 allowed mixed gauge as an “experiment” by adding a third rail to also accommodate the broad gauge, so long as it was not “found to be dangerous”. Brunel’s gauge was thereby back on the field, and the war continued.

Small companies proposed new lines and willingly altered their configuration to attract the best deal with the majors. The Shrewsbury & Birmingham Railway (S&BR) was to use L&NWR’s infrastructure into Birmingham, but this entitlement would cease if it merged with GWR. The S&BR subsequently engineered their line wide enough to accommodate broad gauge at little cost and allied with GWR, but attempted to enforce its L&NWR running powers. Carter was at the “scene of great confusion and excitement” in 1851 where several thousand “roughs” had assembled ready for “bloodshed” (along with the military, police and the mayor), when a S&BR train “bunted against” the large L&NWR engine blocking the track and in steam. A few hours later, “in an able address” at the magistrate’s court, he defended his company’s position as “not a wilful, but a salutary obstruction”. He and Robert Stephenson continued to cite safety concerns in parliament, with Carter emphasising “the inconvenience and peril” of “rival companies” using the same facilities. GWR later completed connections to its own Birmingham station and, in this way, two distinct railway systems were retained.

It was the late 1860s before the spread of Brunel’s gauge passed its peak and the contests ended, which a friend of the GWR bemoaned “have been profitable to no one save Messrs. Carter”. The expensive job of modifying the tracks and scrapping the trains gradually followed and the GWR ceased to operate the broad gauge near the end of the century.

The London & North Western Railway and Midland Railway had lodged a bill to amalgamate in 1853, but parliament’s view was that competition was in the public interest. Thereafter the strategies of the two majors began to diverge markedly, with Carter lamenting: “I am sorry to say they are not friends”. One of the ways he handled the increasing conflict was by establishing separate firms. He first “associated with” John Swift and William Wagstaff, with whom he had long collaborated as they had been engaged by another of the original L&NWR companies. He was later also “the head of” a business with fellow Birmingham solicitors William John Beale and James Marigold, whom he introduced to MR’s parliamentary activities in the early 1860s. These arrangements in addition enabled Carter to focus on “extraordinary” matters: “The board consult me when… they think there is some necessity for it”. They also created the means for his gradual withdrawal from business – Beale & Co continues today and the firm remained MR’s solicitors until World War I and the Railways Grouping Act ended its separate identity.

In this period, Carter and his wife Maria purchased a 663-acre property at Battle, near Hastings, with views “of unusual beauty and extent” from Battle Abbey to the sea. They built a “moderate-sized mansion” with “varied and pleasing” gardens and oversaw the farms – they enjoyed outdoor pursuits. They also became involved in the community: Carter chaired meetings on local issues, their gardener won prizes at the East Sussex horticultural society, and cricket matches against other towns were played on one of their fields. The family did some travelling as well.

In this period, Carter and his wife Maria purchased a 663-acre property at Battle, near Hastings, with views “of unusual beauty and extent” from Battle Abbey to the sea. They built a “moderate-sized mansion” with “varied and pleasing” gardens and oversaw the farms – they enjoyed outdoor pursuits. They also became involved in the community: Carter chaired meetings on local issues, their gardener won prizes at the East Sussex horticultural society, and cricket matches against other towns were played on one of their fields. The family did some travelling as well.

Carter and Maria were soon “exercising a large hospitality” at their country home, and their son Hugh’s paintings give some inkling of the family’s “very wide circle of respect and friendship”. Portraits from Carter’s business world include the pre-eminent civil engineering contractor of the era, Thomas Brassey, railway executive Sir Edward Watkin and his daughter, solicitors Swift and Wagstaff, and judges. Alexander Blair, author and Professor of English and Rhetoric, exemplifies their literary friends.

An illustration of Carter’s “tender nature” and “remarkable” “attention to his family” is his efforts to bring recognition to Francis Ronalds for having invented the electric telegraph. Letters he published in the newspapers reminding the public of his brother-in-law’s achievements assisted in gaining Ronalds his knighthood. Carter also enacted Ronalds’ wish to give his collection of electrical books to the Society of Telegraph Engineers, although Carter went much further than Ronalds had imagined when he moulded the bequest into the “Ronalds Library”, which was soon renowned internationally. Carter was elected an honorary member of the Society in thanks. As a result of his work, Ronalds is today considerably better known to history than Carter.

Carter now also found time to pursue issues outside the interests of the two majors. It became apparent in 1857 that the registrar of the Great Northern Railway had created and cashed in over £200,000 worth of fictitious stock for himself. The company’s “covertly” promoted bill to spread the loss to all stockholders met “vigorous” opposition by spokesmen “governed in their tactics by Mr. Carter”. In Chancery he and other preference shareholders gained their desired result of guaranteed dividends as stipulated in the original act and the threat of denting public confidence in this type of stock was averted.

In 1863, the people of Sheffield desired the Midland Railway to build a direct line through their town but the mayor undertook to promote an alternative scheme. It occurred to Carter that, while much had been heard about the mayor’s idea, its backers had not been publicised, and he discovered that the deposit of capital required by the government as security against speculation had been borrowed rather than being the down-payment of many shareholders. This circumvented parliament’s intentions and was exposed “for the first time” as a result of Carter’s petition. His arguments helped ensure that the Midland Railway project was chosen over its competitor and that parliament in future more thoroughly scrutinised the competency of promoting teams.

The L&NWR decided in late 1861 to bring its legal activities inside the company rather than rely on the services of Carter, Swift & Wagstaff. Carter remained solicitor to at least one of its affiliated companies however, the West London Extension Railway, with which he had worked as early as 1845 when the L&BR had bought into it.

One of the final railway contests for “the veteran Mr. Carter” was to secure the MR’s own route to Scotland via the Settle-Carlisle Railway. He was pitted against his well-trained former junior partner, now the L&NWR law clerk, who nonetheless acknowledged his old boss’s “ingenious mode of putting the matter”. Carter was one of the dignitaries who celebrated the opening in 1876 in a special train trip and it was probably his last such excursion. Passing through remote and rugged terrain, the Settle-Carlisle Railway route remains one of the great railway journeys.

Carter had “confided” “his wish to retire” in 1866 but stayed on following the Midland Railway chairman’s “strong entreaty”. He tried again the next year “but upon its being represented to him that it was of great importance to the company that he should continue” he agreed to a postponement. He finally succeeded the following year when he was elected to parliament. By the time he left each of the majors, they had grown with his help from nothing to nationwide networks across the east and west of Britain, stretching from Scotland to iconic terminals in London (Euston and St Pancras) with interlinking lines around the metropolis.

Politics had always been important for the family. Carter’s uncle, Coventry town clerk John Carter, had led the campaigns of favoured Coventry parliamentary candidates. His father had assisted and his uncle Josiah Corrie had provided legal advice to the sheriff during these elections. Carter himself engaged in East Sussex politics when he became a landholder at Battle. He chaired meetings and accompanied his candidates at the polling booth. His uncle John Carter was a Tory, the Corries were Whigs while Carter was “a Liberal to the backbone”. He had been an active promoter of the Birmingham Political Union that successfully agitated for the Reform Act of 1832 and was a member of the Reform Club.

Elections at this time were boisterous but Coventry was long notorious for “riot”, “assaults”, and “corruption, and general villainy”. The Liberal Henry Jackson had won a by-election but was unseated on Saturday 14 March 1868 by allegations of bribery. A new candidate needed to be found immediately. Carter had attended the inquiry and a conversation convinced him to stand, on the condition that “his election should be fought with perfect purity” and “he would know of every payment”.

By Monday he was in Coventry with his statement of views printed and Thursday saw the key campaign speech to 5,000 Liberals. At its end “every hand was held up, and the ladies waved their handkerchiefs. The applause was deafening, and the scene most exciting”. The following Wednesday he and the Tory candidate were officially nominated and, as was typical, this was “interrupted by the throwing of… missiles into the hustings”. The election the next day was, unlike the norm, “conducted with order and decency” and Carter won “by a considerable majority”. The announcement brought a “triumphant procession… when an enormous crowd of many thousands started… to perambulate the City… and two bands of music”. The Tory newspaper, which referred to Carter as “the Socinian candidate”, noted that “many Churchmen, to their shame” had voted for him, “showing with how much alacrity they could sacrifice a Divinity, and knock the very keystone out of the Christian system”.

Carter was sworn in the following day and (unusually) did not miss a day of attendance in the house. True to his faith, he was “especially devoted to the removal of all disabilities affecting the rights of conscience and the fullest application of the principles of religious equality”. His maiden speech just a few days later was on this theme. He supported the contentious proposal of disestablishing the state-funded (Anglican) Church of Ireland, “the Church of the few… dominant over the many” as he characterised it. He also backed a bill to open academic positions at English universities to non-Anglicans.

With the government contemplating revisions to railway regulation, he “pointedly inquired” whether a particular act—passed nearly 40 years earlier—was suitable to meet present-day requirements. The changes that would benefit his constituency (but not the railways) were subsequently made.

There was a general election in November that year but neither Carter nor fellow Liberal Henry Jackson won seats; Coventry was in a period of depression and Liberal policies were blamed. He offered himself once more at the next election in 1874 but was again unsuccessful.

To commemorate Carter’s retirement from politics “a great meeting” was held and he and 350 others were “entertained to dinner”. Despite his very short term, the description of the event occupied 9½ long columns of the Liberal Coventry Herald. His “magnificent testimonial” was a “massive silver” centrepiece “enriched with precious stones” for the display of flowers and fruit. He was also presented with a gold watch by 200 members of the new Liberal Club in Coventry. It was a club that he had helped form “where working men may meet for purposes of intellectual improvement… or for the interchange of thought”. Both the watch and the centrepiece had been designed and made locally. Carter used the emotional occasion to talk about “civil and religious liberties”, “relations between the Church and State” and non-sectarian education.

Like other Unitarians, Carter had “zeal for the intellectual welfare of his fellow citizens” and strove to make useful education available for working people. He had funded books, prizes and an “architecturally striking” building for the Coventry School of Art, laying the foundation stone in 1862; its goal was to enhance the style and appeal of local manufacture by cultivating art and design skills. When a site became available to establish a Free Library a decade later, he “at once gave £1,000 towards the new building”. There were apparently “many other acts not so well known” towards Coventry’s welfare as well as “private acts of generosity” “where help was needed”.

Like other Unitarians, Carter had “zeal for the intellectual welfare of his fellow citizens” and strove to make useful education available for working people. He had funded books, prizes and an “architecturally striking” building for the Coventry School of Art, laying the foundation stone in 1862; its goal was to enhance the style and appeal of local manufacture by cultivating art and design skills. When a site became available to establish a Free Library a decade later, he “at once gave £1,000 towards the new building”. There were apparently “many other acts not so well known” towards Coventry’s welfare as well as “private acts of generosity” “where help was needed”.

Retaining keen interest in government and transport in his last years, not least as a shareholder, Carter noticed that parliament was inclining towards greater control of the railways. He found “obscure provisions” in 1873 legislation that gave the new Railway Commissioners power to fix the rates a company could charge below those given in its act, without right of appeal. In his words, parliament had viewed the development of the railways as “spend your money if you like, and run the risk”. Carter felt rate intervention now would be a “manifest injustice” and shake the confidence of all who had invested based on the original rules. He was particularly worried about railway debentures, which were considered to be a safe investment even though their holders had no representation on company boards. He highlighted his concerns by publishing pamphlets and writing letters to the newspapers. The campaign elicited a few letters to the press and received notice in railway magazines and at shareholders’ meetings, but overall it was considered to be an unlikely scenario.

Samuel Carter died in 1878, shortly after completing his last pamphlet. He had wanted a private burial “of the simplest character” in the Corrie-Carter family vault at Kenilworth but numerous friends, colleagues and local office-holders “spontaneously attended”. His “intimate friend” Reverend John Gordon conducted a memorial service to “a large congregation” the following week at the Great Meeting House in Coventry where Carter had worshipped as a child.

The altered regulatory rules that Carter had predicted in his pamphlets would be incorporated in future Railway and Canal Traffic Acts passed after his death.

The National Archives in London, England hold Court of Chancery and early railway company records and the Parliamentary Archives contain railway acts and evidence (HL/PO/PB/5/17/3, HL/PO/PB/5/20/8, HL/CL/PB/2/33/38 quoted). Original letters survive in a number of locations in England including the Royal Society Collections; Coventry History Centre; Institution of Engineering and Technology Archives; University of Nottingham Special Collections; Staffordshire County Record Office; University of Bristol Library; University College London (UCL) Library; and the East Sussex Record Office. Additional items are in the Ronalds Family Papers in the Harris Family Fonds at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada. Carter published the pamphlets Railway Legislation (1874), a revised and enlarged Railway Companies and the Railway Commissioners (1874), and Railway Debentures and the Railway Commissioners (1877). Some of his business correspondence was published in periodicals and newspapers.

His legal activities are outlined in The Gazette and the railway press of the period and he receives mention in books on the British railway network, joint stock companies, individual rail corporations, and biographies of those who built and ran them, as well as guides to Coventry. A short biography is included in D. W. Bebbington, “Unitarian Members of Parliament in the Nineteenth-century” in Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society Supplement (2009). There are obituaries in the Solicitors’ Journal; Law Times; Christian Life; Inquirer; Journal of the Society of Telegraph Engineers; and national and provincial newspapers. He has entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Boase’s Modern English Biography, and various parliamentary references including Parliamentary Representation of the City of Coventry (1894) by Whitley and History of Parliament: The House of Commons, 1832-68.

Article by Beverley F. Ronalds

Posted March 15, 2018