Matthew Caffyn (bap. October 26, 1628, bur. June 1714), an important early British General Baptist preacher and evangelist, was an influential antitrinitarian.

Matthew Caffyn (bap. October 26, 1628, bur. June 1714), an important early British General Baptist preacher and evangelist, was an influential antitrinitarian.

Matthew was the seventh son of Thomas and Elizabeth Caffyn. According to family tradition, Elizabeth was a direct descendant of a martyr of the Marian persecution, possibly John Forman, who was burnt at East Grinstead in 1556. Thomas Caffyn was employed by the Onslow family, who owned Drungewick Manor, near the border of Sussex and Surrey. When Matthew was about 7, the head of the Onslow family adopted him as a companion for his own son Richard. The two boys were educated at a grammar school in Kent and, then, in 1643, sent to All Soul’s College, Oxford to study for the Church of England ministry.

A conscientious and able student of ancient languages, scriptures, and theology, Caffyn came to question both infant baptism and the Trinity and debated these doctrines with his professors. But this series of discourses failed to resolve matters to either party’s satisfaction. Unable to convince Caffyn as to the validity of traditional belief, the university authorities tried unsuccessfully to induce him suppress his own views. He responded to their challenges ‘patiently, clearly and fearlessly’. When, as became inevitable, he was expelled from Oxford, he left ‘with an easy conscience’.

In 1645 Caffyn, now 17, returned to Horsham, his future uncertain. Nevertheless his relationship with his patron remained firm, and it was perhaps thanks to Onslow that he was installed at Pond Farm in Southwater. He lived and worked the land there and at another local farm, in Broadbridge Heath, during the remainder of his life.

Soon after he returned to Horsham, Caffyn was appointed assistant to the local General Baptist minister, Samuel Lover. During this period their religious meetings were held in private houses. Caffyn’s campaigning vigour brought about a significant increase in local adherents, and, perhaps as early as 1648, he took over the ministry from Lover. By the age of 25 he had become a denominational leader, and had been appointed a ‘messenger’. He was one of the few General Baptist leaders who had received any university training.

At the same time he was active as a preacher and propagandist in the towns and villages round about. He engaged in vigorous debate and dispute with the Quakers, for whom Horsham had become an important centre (William Penn had a house nearby at Warminghurst), and there is a famous account of an encounter in 1655 when Thomas Lawson and John Slee, two Friends from the north, disputed doctrine with him. The result of their debates was a pamphlet by Lawson entitled An Untaught Teacher witnessed against (1655) and Caffyn’s Deceived and Deceiving Quakers Discovered, their Damnable Heresies, Horrid Blasphemies, Mockings, Railings (1656). Caffyn also opposed George Fox, when he held a meeting in the area.

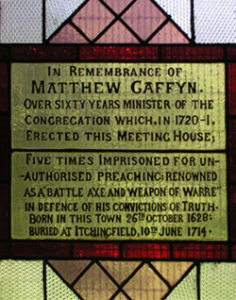

Caffyn’s increasing influence, through persuasive oratory and skill as a polemicist, was felt throughout Sussex, Kent, Surrey, Hampshire and further afield. There was, for example, a public debate between Caffyn and the Anglican minister at Waldron parish church, as a result of which two local men were converted, one of whom became pastor to the Baptist congregation at Warbleton. The vicar of Henfield challenged Caffyn to a public debate in Latin, in the presence of other ministers, hoping to show him up, but Caffyn’s university education stood him in good stead and he won the day. His supporters thereafter called him ‘their battle axe and weapon of warre’.

Caffyn fell out with Richard Haines, a member of his congregation who been close to him for a long time. Haines, a successful farmer, social reformer, inventor and author, promoted schemes for prevention of poverty and setting up ‘working alms houses’, invented a new way of cleaning clover seed from the husk, and applied for a patent for making ‘cider-royal’. These ventures brought Haines into contact with men of influence, such as the Earl of Shaftesbury, and elicited disapproval from Caffyn, who held that patents were covetous and was uncomfortable with Haines’s entry into a social milieu which he considered too far removed from the ‘truly pious’. In 1672 Caffyn excommunicated Haines on the grounds that his greed was a cause of scandal and reflected badly on the church. The following year Haines appealed formally to the General Assembly. The matter was finally resolved in 1680, when the Assembly reversed the excommunication and ordered Caffyn to rescind it.

In 1691 Joseph Wright denounced Caffyn to the General Assembly for stating, in a private conversation, objections to parts of the Athanasian creed. This, Wright claimed, amounted to denying both the divinity and the humanity of Christ. Accordingly, he moved for Caffyn’s excommunication. But Caffyn’s defence satisfied the Assembly, as it did when the matter was raised again in 1693, and later in 1698, 1700, and 1702. He took the Socinian view, which denied Christ’s deity. When the Assembly refused to vote for Caffyn’s expulsion, a rival Baptist General Association was formed. For many years Caffyn’s Unitarian ‘heresy’ was a continual source of debate. During his own lifetime his adherents were known as ‘Caffynites’. A pamphlet by Christopher Cooper of Ashford quoted one of his opponents who called his views ‘a fardel of Mahometanism, Arianism, Socinianism and Quakerism’.

During the period of the Restoration (1660-1688) the British Parliament passed several Conventicle Acts, attempting to suppress non-conformist worship. The first act, in 1664, made it illegal for more than 5 persons over the age of 16 to assemble together for worship, except according to the rites of the Book of Common Prayer. A more severe act was passed in 1670, whereby a justice of the peace could convict without evidence if he believed a conventicle had been held. This suppression of Baptists and other dissenters continued until the 1689 Toleration Act, an important step towards freedom of worship. During the time the Conventicle Acts were in force, Caffyn was fined and had his livestock seized. He was imprisoned five times, once for about a year in Newgate, ‘where he lay some time in a loathsome dungeon, and hardly escaped with his life’, until the Onslow family obtained his release. He also spent time in Maidstone and Horsham gaols.

In 1653 Caffyn married Elizabeth Jeffrey, from another General Baptist family, whom he met while preaching in Kent. They had 8 children: Joseph, Daniel, Sarah, Benjamin, Thomas, Stephen, Jacob and Matthew. Caffyn was a frugal man, and managed to support his growing family with little help from his church. During his last imprisonment he was supported by the industry of his wife, who remained productive at her spinning wheel. She died in 1693. Matthew the younger was ordained a General Baptist elder by his father in 1710, and, together with Thomas Southon, took over the Horsham ministry. It is said that Matthew the elder was buried under an old yew tree in Itchingfield churchyard, but any stone that may have marked his grave is now gone. His only remaining memorial is a window dedicated to him in the Unitarian church in Worthing Road, Horsham.

Among Caffyn’s other publications are Faith in God’s Promises the Saint’s Best Weapon (1661), Envy’s Bitterness Corrected (1674), A Raging Wave Foaming Out its Own Shame (1675), The Great Error and Mistake of the Quakers (n.d.), and The Baptist’s Lamentation (n.d.). Sources of information on Caffyn, his contemporaries, and his church include Mark Anthony Lower, The Worthies of Sussex (1865); Florence Gregg, Matthew Caffin, a Pioneer of Truth (1890); Charles Haines, Complete Memoir of Richard Haines, 1633-1685 (1899); Emily Kensett, History of The Free Christian Church, Horsham (1921); John Caffyn, Sussex Believers (1988); Victoria County History of Sussex, Vol VI, Pt II; and Dictionary of National Biography (2000).

Article by Brian Slyfield

Posted July 26, 2009