Georgene Esther Bowen (February 13, 1898-September 1984) was a Universalist missionary and social worker. She worked at the Blackmer Home for underprivileged girls in Japan and with girls clubs, settlement houses, and the elderly in the United States.

Bowen was born in South Charleston, New Hampshire, to George and Mary Bowen. Her mother who had taught school was now a homemaker; her father earned his living from several occupations including farming and lumbering. When she was four, he moved the family into a house he had built in nearby Bellows Fall, Vermont.

There she attended the public school majoring in classical studies, took singing lessons and with her family was active in the local Universalist Church. Its minister until she was twelve, Fenwick Leavitt Sr., was the first to spark her interest in the Universalist missionary movement in Japan. Clifford Stetson, minister at nearby Rutland and Springfield before

he served as a missionary, further developed it.

Bowen wanted to go to college after she graduated from high school in 1916. Her mother opposed college but allowed her to take a year of teacher training. After Bowen’s mother died in October 1917, her father, who was proud of her singing ability, suggested that she attend the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston.

She enjoyed voice, piano, harmony, and musical history classes at the Conservatory. She also learned to play the then-popular ukulele which she used later in the classroom. Her teachers encouraged her to prepare for the concert stage. She worked for the Woman’s Land Army of Farmerettes in Walpole, New Hampshire in the summer of 1918. In the fall, her father told her that he could no longer pay her tuition and that she would have to support herself.

By chance, she had the opportunity to be a summer volunteer at Sleighton Farm, the Pennsylvania State School for delinquent girls, one of the most progressive reform institutions in the country. Bowen enjoyed the work and soon joined the regular staff. In 1919, at the suggestion of the Sleighton Farm director, she took a position as Director of Music and Recreation at the State Industrial School for Girls in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

The following year, after training in New York City with the National League of Girls’ Clubs, Bowen was appointed Executive Secretary of the North Adams, Massachusetts, Girls’ Club. It had a membership of 330 business and industrial girls. In 1922, she added the task of supervising other clubs in her region. The following year she was appointed Executive Secretary of the Rhode Island League of Girls’ Clubs with over three thousand members. Bowen was not happy; these were desk jobs and she preferred to work directly with students.

When Susan M. Andrews from the Universalist Women’s National Missionary Association (WNMA) asked Bowen to join their missionary effort in Japan, she accepted. Before leaving she completed several religion courses at Boston University paid for by the WNMA and she served as the leader of Camp Murray, the WNMA summer missionary training program for women held at Northfield, Massachusetts.

Her final preparation before sailing to Japan was to attend the 1925 Universalist summer conference at Ferry Beach, Maine. At the end of the conference, the officers of the WNMA organized a Consecration Service where they encircled Georgene as she kneeled, placed their hands upon her, and blessed her and her future work in Japan. “It was,” she later wrote, “as binding to me as a wedding ceremony. I intended to give my whole life to the service in Japan.”

The Universalist Church had started its mission activities in Japan in 1890. Always small and underfunded, Universalist involvement ended with the Second World War although a tiny native movement survived. Headquartered in Tokyo, Japan, the mission established several congregations. Fortunately it consistently had able missionaries and converts.

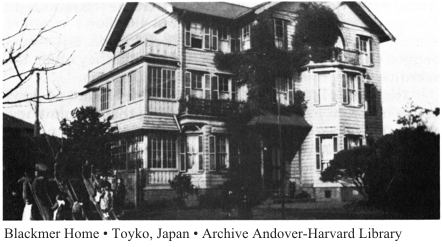

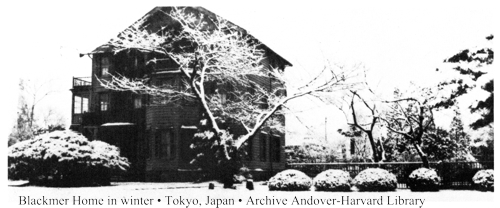

In Tokyo, Bowen worked as assistant to Alice G. Rowe, the Director of the Blackmer Home for Girls. Built in 1903, it was named for its principal benefactor Lucian Blackmer. The Home, which housed twenty girls, became a project of the WNMA. To augment its programs it ran a kindergarten and a Sunday school, both taught by the girls living at the Home. Bowen had a warm personality, and she became a lasting friend and “second mother” to many of her charges.

In 1927, she succeeded Rowe as Director. Among her duties were the management of the home, care of its finances, learning Japanese, and teaching Bible classes to children and adults. One of her enduring achievements was converting John Shidara to Universalism. When Roger F. Etz, the General Superintendent of the Universalist Church of America, visited Japan in 1934 Bowen assisted him in ordaining Shidara, who continued his involvement with Universalism after the war. Bowen wrote numerous article and pamphlets about the work, some in Japanese, and during her furlough in 1930-31 she lectured widely to church, convention, and other groups.

In 1937, Bowen returned to Boston where she met with the leaders of the Association of Universalist Women (AUW), the successor organization to the WNMA. They discussed a third missionary tour and the future of the Blackmer Home. Bowen and the Japanese leaders wanted to make the home coeducational but the AUW refused. When the AUW was unable to assure her that the financial situation would improve or that salaries would be paid on a regular basis, she resigned.

With her missionary career over, Bowen contemplated becoming a religious educator. Realizing she had no money to pay for her studies she decided to try settlement work, volunteering at Hull House in Chicago, Illinois. She was soon the assistant director. Eight months later she became director of activities for Bethlehem Center and then in 1940 director of Bethlehem Creche, both small settlement houses also in Chicago. She resigned the latter position in 1941 when she was told to turn away black children.

Bowen moved to New York City where she was head worker at Grosvenor Neighborhood House. Her task was to reorganize the home and make its programming more acceptable. With older men away at war the neighborhood was increasingly dominated by youth gangs. Bowen gained the respect of the gang leaders and started a community council to coordinate the work of various agencies fighting juvenile delinquency.

Bowen was horrified by the animosity toward the Japanese people that the U.S. government and institutions encouraged during the Second World War. “Wherever I went,” she said, “I encountered so much hatred and prejudice I was unable to talk about my happy excursions in Japan or my faith in the Japanese people.”

By the end of the war, she was ready for a change from working with delinquent youths. She applied for and was accepted by the Board of the Philadelphia Recreation Association as community organizer for the aged. Bowen spent the next fourteen years at this task.

Working on her own as Director of Education-Recreation for Older People, she established 172 clubs for the elderly in Philadelphia and the neighboring counties of Delaware and Montgomery. Lay and professional people in related agencies joined with her and intensified their own efforts to deliver services to the aged. She wrote in her memoirs that “The idea of clubs for older people was such a new concept that newspapers, magazines, and professional journals picked up the new idea and called it ‘The Philadelphia Project.'”

To further the diffusion of her ideas Bowen wrote Summer is Ageless: Recreation Programs for Older Adults (1958) published by the National Recreation Association and To Brighten the Later Years (1960) published by the Health and Welfare Council. She also publicized her work by attending gerontology conferences in America, Italy, England, and Japan. During her 1958-59 trip to Japan, she visited her old friends from the Blackmer Home in addition to promoting the formation of clubs for elderly Japanese citizens.

By 1960, over three thousand “Golden Age Clubs” for older people had been formed. This grew to six thousand by 1965. Bowen also established summer camps, three vacation houses, and worked to make classes at local universities available to older people.

Hundreds of thousands of seniors had participating in the activities of the clubs she founded in Philadelphia by the time she retired in 1963. The Mayor of Philadelphia recognized Bowen for her “Pioneer Work in the Field of Recreation for the Aging in the Philadelphia area.” Her work, he declared, had made Philadelphia the first American city to sponsor on a large-scale such programs for their older citizens.

Bowen continued to live a busy life in retirement. During the summers of 1963 and 1964, she directed one of the summer camps she had organized. In 1964, she made a second, longer “sentimental” trip to Japan where she held reunions with the Blackmer “girls,” met with various Universalist organizations, and visited the graves of missionaries who had died in Japan. At one point, the “girls” gave her a ukulele so that she could play “while they

sang, just as we used to do.” She was proud of all of them but especially of Dr. Isoko Hatakayama Hatano, the first woman in Japan to receive a doctorate in psychology.

Death

In 1970, Bowen became a resident of the Unitarian Universalist House in Philadelphia. She had assembled a genealogy of the Bowen family in 1960; now she wrote her memoirs. She also wrote the story of the Messiah Universalist Home, 1900-1964, a predecessor of the home where she lived, and the story of the First Universalist Church in Philadelphia. Bowen continued to stay in touch with her beloved circle of Japanese students. She was proud of them all. She died in September 1984.

Sources

Georgene Bowen’s papers, memoirs and copies of some of her pamphlets and articles are housed in the Andover-Harvard Theological Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard also holds the records and correspondence of the Universalist Church of America and the Women’s National Missionary Association. For biographical data see her memoirs and “A Universalist Missionary to Japan 1925-1936” (1984). For background information on the Universalist mission in Japan, see Russell E. Miller, The Larger Hope The Second Century of the Universalist Church in America 1870-1970 (1985), Carl Seaburg, Dojin Means All People: The Universalist Mission to Japan, 1890-1942 (1978), and Mary Agnes Hathaway, The Blackmer Home Girls (1927).

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted September 27, 2011