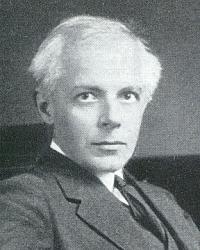

Béla Bartók (March 25, 1881-September 26, 1945), the greatest Hungarian composer, was one of the most significant musicians of the twentieth century. He shared with his friend Zoltán Kodály, another leading Hungarian composer, a passion for ethnomusicology. His music was invigorated by the themes, modes, and rhythmic patterns of the Hungarian and other folk music traditions he studied, which he synthesized with influences from his contemporaries into his own distinctive style.

Bartók grew up in the Greater Hungary of the Austro-Hungarian Empire which was partitioned by the Treaty of Trianon after World War I. His birthplace, Nagyszentmiklós (Great St Nicholas), became Sînnicolau Mare, Romania. After his father died in 1888, Béla’s mother, Paula, took her family to live in Nagyazöllös, later Vinogradov, Ukraine, and then to Pozsony, or Bratislava, in her native Slovakia. When Czechoslovakia was created Béla and his mother found themselves on opposite sides of a border.

A smallpox inoculation gave the infant Béla a rash that persisted until he was five years old. Because of this he spent his early years in isolation from other children, often listening to his mother playing the piano. Béla showed precocious musical ability and began to compose dances at the age of nine. The frequent moves of the family were motivated, in part, by Paula Bartók’s desire to obtain the best possible musical instruction for her son.

At Pozsony Bartók studied piano under distinguished teachers. He taught himself composition by reading scores. Under the influence of composer Ernö Dohnányi, four years ahead of him in his school, teenage Bartók wrote chamber music in the style of Brahms. In 1899 Bartók followed Dohnányi to the Academy of Music in Budapest. While at the Academy Barták heard a performance of Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, which showed him, as he later recalled, “there was a way of composing which seemed to hold the seeds of a new life.” Combining his new enthusiasm for Strauss with his youthful Hungarian nationalism, in 1903 Bartók produced his first major work, the symphonic poem, Kossuth, honoring Lajos Kossuth, hero of the Hungarian revolution of 1848.

After graduating from the Academy Bartók began a career as a concert pianist. During his adult life Bartók performed in 630 concerts in 22 countries. In 1907 he became a piano instructor at the Budapest Academy. Although he did not especially care for teaching, he remained in this post for more than twenty-five years. His most notable contributions to pedagogy were the teaching editions he made of the works of Bach, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven and the pieces he composed for children.

In 1904, while staying in the Slovakian countryside in order to practice and compose, Bartók overheard Lidi Dósa, a Székely Hungarian woman from Transylvania, sing the song Piros alma (“Red Apple”). He then interviewed her to find out what other songs she knew. This encounter was the beginning of Bartók’s lifetime fascination with folk music. Two years later Bartók was introduced to Kodály, who soon became his closest friend. Kodály had already begun to collect recordings of Hungarian folk music using an Edison cylinder. Bartók began his collecting in Hungary’s Békés County in 1906.

Unlike Kodály, Bartók also became interested in other folk traditions, studying the folk music of Romanians, Slovakians, Serbs, Croatians, Bulgarians, Turks, and North Africans as well as Hungarians. In 1906, while visiting Algeria, Bartók had a vision of how he might begin to order scattered folk tunes of the world. This, as he recalled, ended any desire on his part for the kind of career others had projected for him, as “the future master of the most charming salon music.” Afterwards, the main task of his life was to collect, analyze, and catalogue major portions of the world’s folk music.

This multi-ethnic interest caused Bartók trouble, especially after World War I when Slovakians and Romanians were no longer part of Hungary. Areas in which Bartók had previously been free to explore and do research were no longer open to him. Moreover, he endured much criticism at home for his “unpatriotic” interest in the peoples of nations hostile to Hungary. Nostalgic for the ethnic diversity of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bartók dreamed of the “brotherhood of people, brotherhood in spite of all wars and conflicts.”

In 1907 Bartók made his first trip to Transylvania to study the Székely people who had developed in isolation from other Hungarians and might, thus, have preserved some of the more ancient traditions. While he was staying amongst these people, Bartók first became acquainted with the Unitarian Church.

Bartók had been brought up as a Roman Catholic. The ethical legalism taught in the religion classes at school drove him away from his early faith. “By the time I had completed my 22nd year,” he later wrote, “I was a new man—an atheist.” In a letter written in 1905 Bartók claimed to be a follower of Nietzsche and expressed his skepticism about religious teachings: “It is odd that the Bible says, ‘God created man,’ whereas it is the other way round: man has created God. It is odd that the Bible says, ‘The body is mortal, the soul is immortal,’ whereas even here the contrary is true: the body (its matter) is eternal; the soul (the form of the body) is transitory.”

Two years later, shortly after leaving Transylvania, Bartók wrote two letters to violinist Stefi Geyer which contain his most detailed statement of religious belief. Bartók called the trinity a “clumsy fable” that “enslaves thought.” “That mystical mumbo-jumbo” was not to be blamed on Jesus, who was only a moralist—though a great one. He called the conception of God as “a bodiless, everlasting and omnipresent Spirit who has decreed all that has happened in the past, and similarly ordains the future,” a “muddled notion.” The existence of the universe did not require the hypothesis of a creator, Bartók thought. “Why don’t we simply say: I can’t explain the origin of its existence and leave it at that?”

Bartók thought life’s meaning was not directed towards immortality or the afterlife, but to “give a few people some minor pleasures” and to “have a zest for life, i.e. a keen interest in the living universe.” “If I ever crossed myself, it would signify ‘In the name of Nature, Art, and Science.'” He concluded his first missive with, “Greetings from An Unbeliever (who is more honest than a great many believers).”

In 1909 Bartók married Márta Ziegler. Their son, Béla Jr., was born in 1910. In the presence of his son Bartók declared his conversion to Unitarianism on July 25, 1916, and joined the Mission House Congregation of the Unitarian Church in Budapest in 1917. Formal church affiliation enhanced Bartók’s prospects for additional employment and enabled his son to avoid otherwise mandatory Catholic religious instruction. Father and son attended the Unitarian Church regularly. Bartók was briefly the chair of a music committee, but was not a success in this role. He had strict and conservative ideas about church music and would have forbidden the use of any instruments other than an organ.

Béla Bartók Jr. later wrote that his father joined the Unitarian faith “primarily because he held it to be the freest, most humanistic faith.” Although Bartók was not conventionally religious, “he was a nature lover: he always mentioned the miraculous order of nature with great reverence.” Nature was Bartók’s hobby as well. He collected specimens: plants, minerals, and, especially, insects. Later in life he expressed his philosophy using a homely image drawn from nature: “There is life in this dried-up mound of dung. There is life feeding on this dead heap. You see how the worms and bugs are working busily helping themselves to whatever they need, making little tunnels and passages, and then soil enters, bringing with it stray seeds. Soon pale shoots of grass will appear, and life will complete its cycle, teeming within this lump of death.”

Bartók’s personal philosophy was stoic and pessimistic. He held himself apart from others, independent of the ambitious struggle after “trifles.” As a consequence he felt lonely. In his first mature work, the opera Bluebeard’s Castle, Bartók translated his own sense of profound spiritual isolation into music. He pursued the same theme in the fairy-tale ballet The Wooden Prince, 1917, and the ballet-pantomime The Miraculous Mandarin.

Written in a more dissonant musical style than his earlier dramatic works, The Miraculous Mandarin tells a sordid modern story of prostitution, robbery, and murder. After its première in 1926 the audience stormed out in a rage and further performances were banned. The conservative Hungarian musical establishment, who preferred music more in the vein of Brahms and Liszt, resisted Bartók’s music. In his dramatic works, Bartók collaborated with writers out of favor with the government. This fact, too, contributed to his lack of acceptance.

By this time, however, Bartók’s international reputation was secure. His two violin sonatas, 1921 and 1922, and the Dance Suite, written in 1923 for the fiftieth anniversary of the unification of the city of Budapest, helped to establish him as an important modern composer. In 1926 he composed a series of major works for piano, including the first of his three piano concertos. His third and fourth string quartets, from 1927 and 1928, in Bartók’s most abstract and concentrated style, are among the works most often cited as masterpieces by music critics.

In 1923 Bartók and his first wife Márta were divorced. Bartók immediately married a piano student, Ditta Pásztory. They had a son, Péter, born in 1924. For Péter’s music lessons Bartók began composing a six-volume collection of graded piano pieces, Mikrokosmos.

Bartók did not like the fascist régime that governed Hungary during the inter-war period. In 1919 he and Kodály were temporarily suspended from their Academy posts for political reasons. In the 1930s Bartók refused to perform or to have his works broadcast in Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy. He even largely avoided playing in Budapest. In 1931 he went to the French Embassy to accept the Légion d’honneur but, when awarded the Corvin Medal that same year, stayed away from the award ceremony because he would have had to accept it from the hand of Hungary’s dictator, Admiral Horthy.

Much of the music for which Bartók is remembered was written in the 1930s, often in response to commissions from abroad. He wrote his fifth string quartet, 1934, for the American Elisabeth Sprague Coolidge. For the Swiss conductor Paul Sacher he composed Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, 1936, the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, 1937, and Divertimento, 1939. Clarinetist Benny Goodman commissioned Contrasts, for clarinet, violin, and piano, 1938. Two other major works of this period were a violin concerto, 1938, and the last string quartet, 1939.

As the European political situation worsened, Bartók was increasingly tempted to flee Hungary. Having first sent his manuscripts out of the country, in 1940 Bartók sailed for America with his wife. Péter Bartók joined them in 1942 and later enlisted in the United States Navy. Béla Bartók, Jr. remained in Hungary. Although he became an American citizen in 1945, Bartók thought of his stay in the U.S. less as emigration than exile. One attraction of the U.S. for him was the opportunity to study a collection of Serbo-Croatian folk music at Columbia University in New York City.

There are reports that the Bartóks lived in abject poverty during their New York years. Although this is not strictly true, they did live in obscurity and were by no means comfortably well-off. When Bartók became ill with leukemia, the American Society for Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) paid his medical expenses and helped him to get better treatment. To ease Bartók’s financial burden the conductor Fritz Reiner and violinist József Szigeti convinced the conductor Serge Koussevitzky to have his foundation commission an orchestral piece from Bartók. The result was Concerto for Orchestra, 1943, Bartók’s most popular piece. In 1944 he composed a sonata for solo violin, written for Yehudi Menuhin. Bartók’s last two major works, a third piano concerto, which includes bird calls and sounds of nature, and a viola concerto, both left unfinished at his death, were completed by his Hungarian colleague, Tibor Serly.

These late pieces caught the spirit of the times. One 1946 review claimed “the music of Bartók ennobles all of music. And the contemporary world will soon be proud to say, ‘We lived in the time of Bartók.'” Many of his works entered and have remained in the orchestral and chamber repertoires.

On September 26, 1945, Bartók died in a New York hospital with his wife Ditta and his son Péter each holding one of his hands. The funeral was conducted by Rev. Laurence I. Neale, minister of New York’s All Souls Unitarian Church. He was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York. In 1988, as the “iron curtain” separating Eastern Europe from the West was being lifted, Béla Bartók, Jr., then lay president of the Hungarian Unitarian Church, was able to have his father’s remains transferred to Budapest. A statue of Bartók stands in front of the Second Unitarian Church in Budapest.

Bartók documents edited by Janús Demény have been published in Zenetudományi tanulmányok (1954, 1955, 1959, and 1962). Demény also edited Bartók Béla levelei/Béla Bartók Letters (1948-71, English translation, 1971). Other letter and document collections are József Ujfalussy, editor, Bartók breviárium (1958, rev. 1980) and Denis Dille, Laszlo Somfai, and Vera Lampert, editors, Documenta Bartókiana (1964-1982). Béla Bartók, Jr. prepared Bartók Béla családi levelei/Bartók’s family letters (1981). See also Victor Bator, The Béla Bartók Archives: History and Catalogue (1963). A large collection of photographs of Bartók is available in Ferenc Búnis, editor, Béla Bartók: His Life in Pictures (1964, English translation, 1972). Benjamin Suchoff’s, Béla Bartók Essays (1976) is a major collection of Bartók’s articles. Suchoff also edited Bartók’s The Hungarian Folk Song (1981) and Béla Bartók: Rumanian Folk Music (1967-75).

In addition to the pieces mentioned in the article above, the list of Bartók’s significant orchestral compositions includes Piano Rhapsody (1904), two suites (1905, 1907), an early violin concerto (1908), Two Pictures (1910), Four Pieces (1912, orchestrated 1921), and Divertimento for String Orchestra (1939). His Two Piano Concerto (1940) is an arrangement of the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion. Further chamber works include two rhapsodies for violin and piano (1928), which Bartók also arranged for violin and orchestra. For piano Bartók wrote 14 Bagatelles  (1908), Allegro barbaro (1911), Romanian Christmas Carols (1915), a suite (1916), 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs (1918), a piano sonata (1926), and Out of Doors (1926). A major piece for voice and orchestra, Cantata profana (1930), is based upon one of the epic Romanian Christmas songs (colinde) Bartók had studied. He also wrote art songs and arranged numerous folk songs. Each of Bartók’s major works have been recorded many times. His own performances on record (and released on CD) include Contrasts with Goodman and Szigeti, the rhapsodies with Szigeti, the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion with Ditta Bartók, folk songs with Maria Basilides, and many piano works, collectively packaged on CD as Bartók at the Piano. On his recordings Bartók also performs Beethoven, Debussy, Bach, Mozart, Kodály, Liszt, and Chopin.

(1908), Allegro barbaro (1911), Romanian Christmas Carols (1915), a suite (1916), 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs (1918), a piano sonata (1926), and Out of Doors (1926). A major piece for voice and orchestra, Cantata profana (1930), is based upon one of the epic Romanian Christmas songs (colinde) Bartók had studied. He also wrote art songs and arranged numerous folk songs. Each of Bartók’s major works have been recorded many times. His own performances on record (and released on CD) include Contrasts with Goodman and Szigeti, the rhapsodies with Szigeti, the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion with Ditta Bartók, folk songs with Maria Basilides, and many piano works, collectively packaged on CD as Bartók at the Piano. On his recordings Bartók also performs Beethoven, Debussy, Bach, Mozart, Kodály, Liszt, and Chopin.

Sources

A recent biography is Kenneth Chalmers, Béla Bartók (1995). Other biographies include Lajos Lesznai, Bartók (1961, Eng. version, 1973) and József Ujfalussy, Béla Bartók (1965, Amer ed., 1972). Béla Bartók, Jr. wrote Apám életének krónikája/Chronicle of my father’s life (1981) and Bartók Béla muhelyében/In Bartók’s workshop (1982). The last years of Bartók’s life are covered by Agatha Fassett, Béla Bartók’s American Years: The Naked Face of Genius (1958). Some particulars of the end of Bartók’s life are in the third volume of the history of All Souls Church, New York, Safely Onward (1991), by Walter Kring. The biographical monograph “Béla Bartók,” by Vera Lampert and Lászlú Somfai in The New Grove Modern Masters (1984), also includes a complete list of Bartók’s works and a detailed bibliography. Collections of essays on Bartók include Malcolm Gillies, editor, The Bartók Companion (1993); Peter Laki, Bartók and His World (1995); and Amanda Bayley, editor, The Cambridge Companion to Bartók (2001). An interview by Laszlo Somfai, “Béla Bartók Jun. on his Father,” New Hungarian Quarterly (Winter 1976), is also included in Malcolm Gillies, editor, Bartók Remembered (1991). There is a tremendous literature on Bartók’s music, including works devoted to single compositions. Among these are Elliot Antokoletz, The Music of Béla Bartók (1984); John McCabe, Bartók’s Orchestral Music (1974); Stephen Walsh, Bartók Chamber Music (1982); Mátyás Seiber, The String Quartets of Béla Bartók (1945); and Benjamin Suchoff, Guide to Bartók’s ‘Mikrokosmos’ (1983).

Article by Peter Hughes

Posted May 17, 2001