Margot Susanna Adler (April 16, 1946-July 28, 2014) was a speaker, lecturer, writer, and public radio reporter. A complex woman with wide-ranging interests, she was willing to go wherever her heart and mind led her, even to a fascination with vampires in later years. A self-described Wiccan High Priestess, she was the author of Drawing Down the Moon, a seminal work on neo-paganism in America. She was a member of the Unitarian Church of All Souls in New York City, a member of the Covenant of Unitarian Universalist Pagans (CUUPS), and a frequent speaker at national and regional Unitarian Universalist events.

Margot Susanna Adler (April 16, 1946-July 28, 2014) was a speaker, lecturer, writer, and public radio reporter. A complex woman with wide-ranging interests, she was willing to go wherever her heart and mind led her, even to a fascination with vampires in later years. A self-described Wiccan High Priestess, she was the author of Drawing Down the Moon, a seminal work on neo-paganism in America. She was a member of the Unitarian Church of All Souls in New York City, a member of the Covenant of Unitarian Universalist Pagans (CUUPS), and a frequent speaker at national and regional Unitarian Universalist events.

The only child of Freyda Nacque (nee Pasternack) and Kurt Adler, she was born in Little Rock, Arkansas where her father was stationed at the end of the Second World War. She was the only grandchild of Alfred Adler, the renowned Austrian doctor and psychologist. Alfred Adler had been a contemporary and associate of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung in Vienna, Austria prior to the Second World War. Her mother was the daughter of unschooled immigrants, both of whom were dead by the time Margot was born. Her mother was charismatic—Margot likened her to Auntie Mame, beautiful, a renowned political activist, and a beloved mother. Her father, a psychiatrist, would always remain a cipher to her.

Both of her parents came from Jewish families although neither of them had practiced the religion nor celebrated its religious holidays. Then in 1951, during a family visit to Germany, her mother reconnected with her Jewish heritage and proclaimed herself–and Margot—Jews. Her father, who had been raised a nominal Lutheran, disagreed.

Adler grew up in Manhattan where she attended the progressive City and Country School located in New York City’s Greenwich Village neighborhood. She called it “. . . my utopia, and the place that remained whole and intact and vibrant, even when my own family fell apart.” As her parent’s marriage crumbled in the mid-1950s, her mother suffered depression, exhibited erratic behavior, and was hospitalized. At times, Adler lived with her father who had moved to a nearby hotel. Like many children of divorce, she ended up closer to her mother. “My mother was the one person to whom I could show all my feelings,” Adler later said, “. . . we could fight and love and laugh on a huge scale.” The City and Country School helped her weather the storm, and it was there that she fell in love with the stories of the gods and goddesses of myth that would later influence her to become a Wiccan priestess. She also developed a love of singing and performance that led her to enroll at New York City’s High School of Music & Art.

Adler described herself as “raised by left wing parents,” she was a red diaper baby at the height of the McCarthy era. Her father was a practicing therapist who devoted his life to analyzing his own father’s theories of human psychology and noting parallels with Karl Marx’s theories of economic socialism. A proponent of equal rights for women, he believed people needed to integrate self-interest with a concern for the community. Perhaps Adler described it best when she wrote, “The only thing that was beaten in my head was the Adlerian notion of ‘social interest,’ which, while never clearly defined in my youth, seemed to have something to do with being cooperative and merging your individual desires with the needs of society—rather like socialism.”

Adler was a freshman at the University of California, Berkeley in 1964 when the Free Speech Movement (FSM) erupted. It started when the university imposed limits on the right to meet and organize around political issues, specifically to enlist students as volunteer workers in the civil rights movement in the South. Campus protests and finally a sit-in at Sproul Hall—the university’s administration building—resulted in the largest mass arrest of students in the nation’s history. Like her mother, Adler embraced political activism; she was drawn by the issues and she felt them deeply. She decided to go to jail rather than pay a $250 fine so she was imprisoned for three weeks in the Santa Rita Prison Farm and Rehabilitation Center in Pleasanton, California.

At the end of her freshman year Adler volunteered to work with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party registering African American voters. This was not a positive experience; there was discord between the volunteers and regular staff workers, women were relegated to support roles, little progress was made registering voters, and the threat of violence was constant. While she was traveling with a group of volunteers in rural Mississippi, their car was rammed and finally blocked by two pickup trucks. Men with drawn guns told the volunteers to get out of the car. Ora, the lone African American was told to start walking to town while Bernie, Ben, and John—white male volunteers—were punched and kicked. Adler was allowed to remain in the car, terrorized but untouched. In the end, they drove back to town and Ora returned unharmed the next day. Three days later Adler left Mississippi and returned home to her mother in New York City.

In the fall she was back on the Berkeley campus, a place at the center of the emerging sex, drugs, and rock and roll counter-culture. “As for me, although I may have looked a little bit like a hippie, “Adler later wrote, “I remained a left-wing nun. Mine was the ecstasy of politics, not of the body.” She would take her first journalism class that fall. In the spring of 1967 she started writing to a GI in Vietnam: He was fighting in a war he didn’t support, but one he had to fight in order to survive. They would exchange over 200 pages of letters. Like many Americans, she was trying to figure out the right response; should she be a good American and support the Vietnam War or should she fight against it by adding her support to those who opposed the war. That fall when he returned to the states they spent several days together in San Francisco. Their love affair didn’t last and there is no record that they stayed in touch. In many ways this episode resembled the romantic stories about herself that she was always spinning in her mind.

In her senior year at Berkeley, she volunteered as a reporter for Pacifica Radio, KPFA, in Berkeley, California. After graduating from Berkeley Phi Beta Kappa with a degree in political science, Adler decided to pursue a career in journalism and was accepted into the Master’s Program at Columbia University in New York City. But this move did not end her political activism. She and a friend, as part of their studies, joined the Venceremos Brigade, harvesting sugar in Cuba to support the Cuban revolution and to counter the crippling impact of the US economic embargo against the country. Her stay ended when she was called back to her mother’s bedside in the final days of her mother’s battle with lung cancer. Her mother died in 1970 at the age of 61.

Adler inherited the family’s rent controlled apartment on Manhattan’s West Side overlooking Central Park. It would be her home for the rest of her life. She referred to that apartment as her bit of heaven on earth, high up on the western edge of Central Park with a view of the city. It came with all of the family mementos stored there since Margot’s childhood, including the letters she had exchanged with that young soldier in Vietnam.

Adler had always felt different or estranged; particularly in regard to her sensuality, her relationships, and her body. She started to realize how common these thoughts and fears were among women, when she joined a feminist consciousness-raising group in 1972. Discussions of life, politics, and spirituality in another group that included men also helped her overcome some of her negative feelings about her body. That group also brought her into contact with the expanding Pagan community in America.

While she was in graduate school, Adler continued her work in radio by reporting for WBAI-FM in New York City. WBAI was a sister station to KPFA Berkeley, one of a handful of listener-supported public radio stations under the aegis of the Pacifica Foundation. In New York City she attended and reported on the “Panther 21” bomb conspiracy trial. The trial lasted eight months before all 156 charges against the 21 Black Panthers were dropped. When the trial ended she was asked to head up a Washington bureau for the Pacifica stations. Reporting from Washington, D.C. was difficult for Adler, she struggled with her weight and body issues and felt “I was way over my head in the strange land of Richard Nixon’s Washington. On the outside I tried to look reasonably ‘straight’ and presentable; I spoke softly and politely. On the inside I was raging.” After a year she returned to New York City.

Reporting for WBAI-FM in New York City she interviewed Joseph Campbell and I. F. Stone and she presented her first programs exploring paganism and witchcraft. She also took part in programs on the Kent State shootings, the Black Panthers, alternative medicine, journalism in Cuba, matriarchy, and feminism. She developed and hosted Hour of the Wolf, a science fiction program, 1972-1974 and she co-hosted with Paul Isaac, Science, Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness. That show featured discussions with scientists such as, Carl Sagan, Marvin Minsky, and Jacques Cousteau. In 1978, Adler started working with National Public Radio (NPR) in addition to her work with Pacifica. The following year she was hired by NPR as a general assignment reporter based in New York City. She worked as a correspondent for National Public Radio for the next 35 years. She was a frequent contributor on the nationally syndicated NPR shows, All Things Considered and Morning Edition. She also hosted the weekly NPR show, Justice Talking, 1999-2008.

As her faith in politics and protest waned she shifted her focus to nature and the environment. Adler found herself moved by a number of deeply emotional passages she found in the works of environmentalists and science writers such as John McPhee, Arthur Toynbee, and Lynn White Jr. She was especially moved by a series of articles written by John McPhee for the New Yorker magazine that chronicled wilderness hikes taken by Sierra Club President John Brower, accompanied by three adversaries of the environmental movement. John Brower likened the environmental movement to a religion. He thought that viewing the earth and nature as sacred space was akin to many Buddhist teachings. One of the developers hiking with Brower likened conservationists to Druids which led Margot on a search to learn more about Druids. She discovered they were “largely portrayed as sorcerers who opposed the coming of Christianity,” particularly its view of the earth and nature as something to be under the dominion of human beings.

She had explored different churches and been enthralled by the Quakers and the ritual of the Catholics, but ultimately found those belief systems foreign and dogmatic. Adler felt a close affinity to the earth-centered worship of the Pagan ceremonies which may have also reminded her of her early attraction to stories of the gods and goddesses about whom she and her primary school friends had written plays. Those stories and performances were empowering to Adler, “The fantasies enabled me to contact stronger parts of myself, to embolden my vision of myself. Besides, these experiences were filled with power, intensity, and even ecstasy that, on reflection, seem religious or spiritual.” This opened to her a spiritual world that did not require a catechism of belief but instead allowed her to suspend rationalism and give herself over to something more akin to art, poetry and music.

In the 1970s Adler interviewed hundreds of people and gathered a wide variety of documents in order to capture and describe the full range of contemporary and historical Pagan practices. She toured England where she interviewed Druids, witches, and Pagans. When she returned to New York she joined a coven. She shared this research in her book, Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today (1979).

In the 1970s Adler interviewed hundreds of people and gathered a wide variety of documents in order to capture and describe the full range of contemporary and historical Pagan practices. She toured England where she interviewed Druids, witches, and Pagans. When she returned to New York she joined a coven. She shared this research in her book, Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today (1979).

She was awarded a prestigious Nieman Fellowship at Harvard in 1982. Male journalists, especially print journalists had dominated the Nieman program for years: Adler found herself in the minority, both as a woman among men and as a radio personality in a group dominated by print journalists.

Adler’s partner in life was John Gliedman. Like Adler, he was the child of a psychiatrist. A psychologist and science writer, he had received his doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. They lived in the apartment overlooking Central Park in New York City that she had inherited from her mother. When it was converted to a condominium they bought it. They held a commitment ceremony in 1976 and then were married on June 18, 1988 in West Tisbury, Massachusetts. The wedding was on Martha’s Vineyard, a place Margot had loved since vacationing there with her parents as a child. The Adler-Gliedman wedding was the first Pagan handfasting to be written up in the society pages of the New York Times. Margot and John had one child, a son, Alexander Dylan Gliedman-Adler born in 1990.

Beacon Press published an expanded edition of Drawing Down the Moon in 1986. The next year Adler was a keynote speaker at the annual Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA) General Assembly (GA). A continental organization, the Covenant of Unitarian Universalist Pagans (CUUPS) was formed and was granted affiliate status with the UUA in 1988. Adler was a member of CUUPS and served on the board. She joined the All Souls congregation in New York City in 1992 and participated in the activities of its Women’s Alliance. She would speak at numerous Unitarian Universalist affiliated events over the next twenty years.

In 1997 Adler published Heretic’s Heart: A Journey Through Spirit and Revolution. It was a memoir of her life and experiences in the 1960s and 70s. It drew on a trove of family letters and documents that her mother had stashed away in the family apartment. In this book, Adler reflected on her family and her life through the mid-1970s. It covered her time as a student activist at University of California Berkeley, her civil rights work in Mississippi, her relationship with the soldier fighting in Vietnam, and the early years of her career in radio.

Adler saw Paganism as the spiritual side of feminism which rejected the hierarchy of monotheism. She thought monotheism was “imperialism in religion.” In 2005 Adler spoke at the annual Southwest Unitarian Universalist Women’s Conference in Houston, Texas. There was still some resistance in Unitarian Universalist women’s circles toward the Pagan movement despite the fact that “Spiritual teachings of Earth-centered traditions” had been named the sixth source of our Unitarian Universalist Living Tradition. In her talk, Adler explained how much pagan spirituality and ritual had contributed to Unitarian Universalist worship; from croning and water ceremonies, to walking the labyrinth, spiral dances, drumming, and—perhaps most importantly for Margot—chanting, a practice she often introduced at women’s gatherings.

In 2009 she spoke at the first International Conference of Unitarian Universalist Women, also held in Houston, Texas. Six-hundred people from 38 states and 17 countries attended. The following year she taught a Paganism course at Meadville Lombard Theological School, the Unitarian Universalist seminary in Chicago, Illinois. Adler University, named for her grandfather, awarded her an honorary degree in 2011. She also wrote an on-line column for BeliefNet (beliefnet.com) for a while. Adler was often asked to explain her pagan beliefs, especially to skeptical audiences. Her response, now widely quoted, was:

“We are not evil. We don’t harm or seduce people. We are not dangerous. We are ordinary people like you. We have families, jobs, hopes and dreams. We are not a cult. This religion is not a joke. We are not what you think we are from looking at TV. We are real. We laugh, we cry. We are serious. We have a sense of humor. You don’t have to be afraid of us. We don’t want to convert you. And please don’t try to convert us. Just give us the same right we give you, to live in peace. We are much more similar to you than you think.”

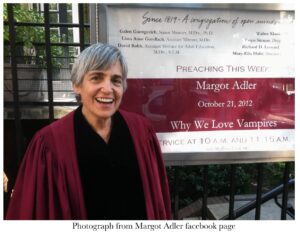

Adler turned to vampires in her later years. Some speculated that her fascination with vampires was related to illness and death. She said she had read close to 300 vampire books, an immersion that began after her husband was diagnosed with stomach cancer. He died in 2010 after they had been together for 35 years. She was diagnosed with cancer the following year.

Adler presented her theories about vampires to the Second International Convocation of Unitarian Universalist Women in October 2012 in Marosvásárhely, Romania. In her keynote speech, Adler compared America’s twenty-first century fascination with vampires to that experienced in Great Britain at the close of the nineteenth century when Dracula, written by Bram Stoker, had been published. She theorized that the two cultures were similar in experiencing the end of empire and perhaps also sharing a view of themselves as evil; the British sucking the blood from colonies while America was sucking oil through powerful multinational corporations. She published Out for Blood in 2013, and Vampires Are Us: Understanding Our Love Affair with the Immortal Dark Side the following year.

Adler presented her theories about vampires to the Second International Convocation of Unitarian Universalist Women in October 2012 in Marosvásárhely, Romania. In her keynote speech, Adler compared America’s twenty-first century fascination with vampires to that experienced in Great Britain at the close of the nineteenth century when Dracula, written by Bram Stoker, had been published. She theorized that the two cultures were similar in experiencing the end of empire and perhaps also sharing a view of themselves as evil; the British sucking the blood from colonies while America was sucking oil through powerful multinational corporations. She published Out for Blood in 2013, and Vampires Are Us: Understanding Our Love Affair with the Immortal Dark Side the following year.

In 2012, Adler participated in a group tour to Eastern Europe. After visiting Prague and Budapest, Adler—along with Harry and Laura Nagel—split off from the group to visit the Unitarian Church in Arkos, Transylvania near Brasov. The Nagels were members of the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Houston (Texas), a partner church to the Arkos congregation. Adler felt like she was returning to her Hungarian roots since Arkos is in a largely Hungarian speaking portion of Romania. It had been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire before the First World War. And of course it was the home of Vlad Drac, the Medieval warrior and nobleman who was notorious for defeating the invading Turks and posting their decapitated heads on spikes outside his castle. Bram Stoker’s Count Dracula had been based on Vlad Drac.

Adler always had her pedometer with her on the trip to Eastern Europe. She kept track of how many steps she took each day. She walked a lot and appeared to be in excellent health. She walked to many of the places where Vlad Drac was supposed to have lived. She especially loved being in the tiny village of Arkos. Adler was “just folk” and didn’t bat an eye about sleeping on a pallet on the floor or sharing space with fellow travelers. The Unitarian minister, his family, and townsfolk all delighted in her company, and she in theirs. Adler shared her love of chanting when the group visited a castle in the hills above Prague. With the woods to themselves, Adler soon had the whole group chanting and singing at the top of their lungs.

Her face became more animated and beautiful as she grew older. She could relax and feel comfortable in her body. Her brown eyes were warm and penetrating, her lips full and wide. She died of cancer in July 2014. Widely mourned and memorialized, many radio listeners had come to think of her as a close personal friend. Her “unflinching honesty” endeared her to her fans. She had always talked about her life in the most intimate terms. For forty years she had shared her sexuality, her spirituality, her qualms, and her scruples with her many radio listeners.

In 2013 Adler placed books from her parent’s collections into the “Margot Adler Collection” at the Adler Graduate School in Richfield, Minnesota. Alfred Adler papers were donated to the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Transcripts and audio copies of some Margot Adler radio broadcasts can be found at justicetalking.org, pacificaradioarchives.org, hourwolf.com, npr.org, and YouTube.

In addition to the books mentioned above, Adler was co-author with her husband of Our Way to the Stars (2000). A number of Adler biographies can be accessed on the internet; Jon Kalish “Margot Adler, Witty NPR Correspondent, Put the Witch in Jewish” Forward.com (2014); Jim Freund “Margot Adler” in the Jewish Women’s Archive at JWA.org; “Memories of Margot by Her City & Country Classmates” (2014) is available at cityandcountry.org; Starhawk “Samhain 14 Remembering Margot Adler” (2014) at starhawk.org; Matthew Sawicki “The Passing of an Elder: Remembering Margot Adler” (2014) at esotericanewyork.com; and Alex Jones “Making Us Belivers: Remembering the magic of Nieman Classmate Margot Adler” which can be found in Nieman Notes (2014) at niemanreports.org. For more on Adler and her beliefs see “Vibrant, Juicy, Contemporary: or, Why I Am a UU Pagan” UUWORLD (1996). Obituaries can be found in a number of magazines and newspapers including the July 29, 2014 New York Times. Also useful is the overview of Pagan, Earth-centered, and Goddess traditions among Unitarian Universalists found in a paper presented at the 2007 UUA General Assembly by Rudra Vilius Dundzila, How do UU and Pagan Thea/ologies Fit Together?: CUUPS 20th Anniversary (2007).

Article by Laura Nagel

Posted December 3, 2016