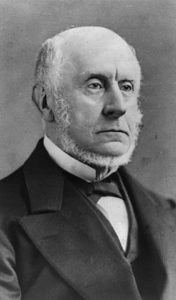

Charles Francis Adams, Sr. (August 18, 1807-November 21, 1886), a lifelong Unitarian, was an antislavery politician who later opposed radical reconstruction of the South. As ambassador to Britain during the Civil War he helped to prevent conflict between the United States and Europe. He prepared for publication the papers and writings of his father, John Quincy Adams, and of his grandparents, John and Abigail Adams.

The third son of Louisa Catherine Johnson and John Quincy Adams, Charles Francis was born in Boston and baptized at First Church by William Emerson, father of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Two years later, he accompanied his parents when his father became minister to Russia. Charles was educated in French, German, and Russian as well as English. He lived in St. Petersburg during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia and moved to Paris at the time of Napoleon’s return from Elba. While his father was minister to England, 1815-17, he attended an English public school. During the years John Quincy Adams served as Secretary of State in the Monroe administration, Charles studied at Boston Latin School, 1817-19; a school in Washington, D.C., 1819-21; and Harvard College, 1821-25.

In 1826 Charles met and fell in love with Abigail Brooks, the youngest daughter of wealthy Unitarian Peter Chardon Brooks and Anna Gorham, daughter of the first president of the Continental Congress. During the period of their engagement, 1827-29, Charles read law at the office of Daniel Webster. He passed the bar examination in 1829, but had few law clients. After his older, emotionally troubled brother George died, Charles took over management of the family’s business, for which service his father provided him an allowance. When he and Abigail married, her father gave them a townhouse on Beacon Hill. They had seven children, of whom six survived. Among their children were Union Pacific Railroad president Charles Francis Adams, Jr., historians Henry Adams and Brooks Adams, and Massachusetts Democratic politician, John Quincy Adams II (1833-1894). The latter’s son, Charles Francis II (1866-1954), a Unitarian, served as Secretary of the Navy in the Herbert Hoover administration.

Continuing the family interest in history, in 1831 Adams wrote a history review for North American Review. He criticized “the modern fashion of what is called philosophical history” as “it admits of the perversion of facts, to suit the prejudices of each particular writer.” He eventually made a number of contributions to the Review, including a substantial article on Aaron Burr in 1839 and one on the Puritans in 1840.

Adams entered politics in 1832 as a member of the Massachusetts Antimasonic party. He thought that Masonry’s “exclusive character, its secret character, its assumption of a sacred character, and inflicting of penalties” were “at variance with the foundation of society and government of morality and religion.” His antimasonic articles in the Boston Advocate, 1832-33, led to his being chosen a delegate to the Massachusetts Antimasonic state conventions in 1833 and 1834. Although he supported Democratic presidential candidate Martin Van Buren in 1836, after the Antimasons were absorbed by Democrats, Adams for several years turned away from political affiliation.

A Burkean conservative, distrusting the tyranny of majorities, Adams was infuriated by the 1835 spectacle of a mob dragging abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison naked through Boston streets. His concern for civil liberties mounted with the passage in 1836 of the gag rule in the United States Congress, forbidding anti-slavery petitions, and the 1837 murder of Illinois abolitionist editor, Elijah Lovejoy. While he opposed the institution of slavery, Adams nevertheless believed blacks inferior to whites.

Because of Adams’s antislavery and articles he had written in the Boston Courier 1840 critical of President Martin Van Buren, the Whig party asked him to run for the Massachusetts General Court (legislature). He served as representative, 1840-43, and then as senator, 1843-45. Beginning with the 1843 session, he led the struggle against slavery in the state legislature. That year he successfully petitioned the General Court to prevent the state from returning fugitive slaves and he brought about passage of a resolution opposing the annexation of Texas as a slave state. After the national Whig party in 1845 endorsed the admission of Texas, he separated himself from the majority “Cotton Whigs,” and associated only with the antislavery “Conscience Whigs.” In 1848 he joined the Free Soil party, composed of former Conscience Whigs and other abolitionists. He chaired their national convention that year and the new party nominated him for vice president. After his unsuccessful candidacy, Charles temporarily withdrew from active politics, devoting himself to writing and business.

During this period, he underwrote and edited the Boston Daily Whig, 1846-48; published Letters of Mrs. Adams, the Wife of John Adams, 1840-48, including his own introductory memoir; and completed The Works of John Adams, 2nd President of the United States, With a Life of the Author, 1850-56, his edition of his grandfather’s papers in ten volumes and his own two-volume biography.

In 1844, spurred by Abigail’s religious crisis and Charles’s increase of seriousness after a near-death experience, the Adamses began family Bible studies and, guided by Abigail’s brother-in-law, Unitarian minister, Nathaniel Frothingham, private prayer sessions. They soon joined Frothingham’s church, First Church in Boston. When in the summer the family stayed in Quincy, Massachusetts, they attended the Unitarian church there. William Lunt, the Quincy minister and a family friend, was greatly respected by Charles. The Adams family spent most of every Sunday in church. “My father had the old New England sense of duty in religious observances,” wrote Charles, Jr., who unlike his father, dreaded Sundays. “The Sabbath and church going were institutions.”

Adams did not agree with the Transcendentalists that human nature could be perfected. Nevertheless, he thought human wisdom “the most desirable thing we can attain.” He believed God good and thought that religion should be cheerful. To live a good life, in his view, was to follow the Golden Rule and to do one’s duty. A moderate in religion, he disliked religious display, enthusiasm, and intolerance. He cared for the certainties of conduct and not the mysteries of metaphysics. Commenting on one of Frothingham’s sermons Adams said, “The doctrines of the Bible are all simple, but the ingenuity of man, has perpetually attached theories to them which obscure and mystify and do injury. Theology has sprung from these theories. Theology is not religion—as an instance the doctrine of the atonement from the simple story of the passion of Christ.”

Following the Kansas-Nebraska Act, 1854, and the Anthony Burns case that same year, Adams looked for a new party alignment to address sectional problems. He firmly rejected approaches by the nativist American (or Know Nothing) Party. In 1856 he became a Republican and was a delegate to their convention in Philadelphia. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1858 and 1860. During the crisis caused by the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, he was appointed to the Committee of Thirty-Three, a special House committee to address the state of the country.

In 1861, on the advice of Adams’s political ally, Secretary of State William Henry Seward, President Lincoln appointed Adams Ambassador to the court of St. James. The Adamses left for Britain shortly after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. When they arrived in London, Britain had recently issued a proclamation of neutrality, recognizing the Confederacy as a belligerent power and, in so doing, granting it the right to purchase arms and commission privateers. Adams and the Lincoln administration worried that this was a step towards British diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy as a new nation. Adams quickly developed a good working relationship with British foreign secretary Lord John Russell. Unfortunately Russell, like many of his countrymen, believed the Southern secession an accomplished fact.

Trouble erupted when an American naval vessel seized two Confederate diplomats, James M. Matson and John Slidell, from the British mail ship Trent. In incidents like this one Adams maintained his composure, relayed his government’s statements and instructions in ways that were relatively palatable to the British, and helped to prevent a war between Britain and the United States. One of his major tasks was to alert the British government that the Confederacy was building vessels in British shipyards that were to be armed as commerce raiders. Among these was a ship, later known as the Alabama, which inflicted great damage on Northern shipping. In 1863 Adams threatened war in order to prevent two Confederate-built ironclad rams from leaving the Liverpool shipyards. Russell, who had already been looking for a legal expedient to detain the ships, settled the incident by buying them for the British government. James Russell Lowell praised Adams’s role as ambassador to Britain, saying, “None of our generals etc. did us better or more trying service than he in his forlorn outpost of London.”

When Adams returned home in 1868, Irish Americans demonstrated against him for his supposed neglect of Fenians claiming American citizenship who were being held in British jails. (Although it was true that he did not help active Irish revolutionaries, he aided those American Fenians willing to leave the British Isles.) His opposition to forced reconstruction of the South and to Negro suffrage had alienated him from the then-dominant Radical Republicans. He avoided any possibility of a potential Democratic Party presidential draft by arranging to arrive home after their convention.

Adams returned to diplomatic service in 1871 to negotiate Civil War damage claims against Britain. President Ulysses S. Grant reluctantly appointed Adams—although the natural choice, he was by then a Democrat—to a commission of five arbitrators in Geneva, Switzerland. There, Adams was instrumental in breaking a stalemate in the negotiations. The tribunal absolved Britain from indirect damages, but awarded the United States 15.5 million dollars for the losses caused by the Alabama and other Confederate raiders.

While a new party, the Liberal Republicans, was meeting in Cincinnati, Adams was enroute to Europe for the Alabama conference. He was willing to consider running for president on their ticket, but not willing to campaign for the nomination. Even so, as the convention began, it seemed probable that he would be chosen. A seventh ballot groundswell, however, selected Horace Greeley, the Universalist New York Tribune editor. Adams was glad to be out of the running.

In 1874 Adams accepted the chair of the Board of Overseers of Harvard University. Reformers in vain promoted his candidacy as president in 1876. The Democrats nominated him for governor that year. While delighted by this honor, he feared winning and, fortunately for him, did not. In retirement he edited the Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848, 1874-77, and revised his biography of John Adams.

As a congressman Adams had rented a pew at the Unitarian church in Washington. In old age he attended either First Parish, Quincy in the summer, or King’s Chapel, which represented a liturgical compromise between his father’s Congregational-style Unitarianism and his mother’s Episcopalianism.

In The Education of Henry Adams, Adams’s son Henry fashioned a portrait of his father’s character: “Charles Francis Adams was singular for mental poise—absence of self-assertion or self-consciousness—the faculty of standing apart without seeming aware that he was alone—a balance of mind and temper that neither challenged nor avoided notice, nor admitted question of superiority or inferiority, of jealousy, of personal motives, from any source, even under great pressure.”

Sources

Adams’s papers are at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts. These are also on microfilm in many other libraries. Some of these primary materials have been published as L.H. Butterfield, et al., eds., Diary of Charles Francis Adams (1964-93) and Worthington Chauncy Ford, A Cycle of Adams Letters, 1861-1865 (1920). Among Adams’s published works, not mentioned above, are An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs (1835); Reflections upon the Present State of the Currency in the United States (1837); Texas and the Massachusetts Resolutions (1844); What Makes Slavery a Question of National Concern (1855); The Struggle for Neutrality in America (1870); An Address on the Life, Character and Services of William Henry Seward (1873); The Progress of Liberty in a Hundred Years (1876); and many articles in North American Review.

Biographies include Charles Francis Adams, Jr., Charles Francis Adams (1900); Martin B. Duberman, Charles Francis Adams 1807-1886 (1961); and the entry by Kinley Brauer in American National Biography (1999). There are a number of collective biographies of the Adams family: Jack Shepard, The Adams Chronicles: Four Generations of Greatness (1975); Francis Russell, Adams, An American Dynasty (1976); and Paul C. Nagel, Adams Women (1989) and Descent From Glory (1983). See also Octavius Brooks Frothingham, Boston Unitarianism, 1820-1850 (1890); Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams (1907, many later editions); and Charles Francis Adams, 1835-1915: An Autobiography (1916).

Article by Wesley Hromatko

Posted May 25, 2005